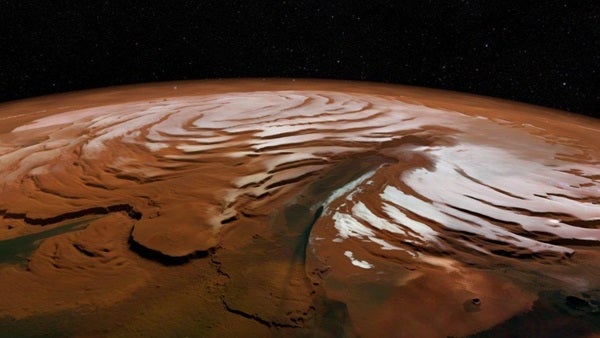

Bands of ice and sand at Mars’ north pole reveal an ancient climate that swung between warm and cold.

Mars, now dry and dusty, still holds water ice at its poles, and evidence strongly suggests it was once a planet where water flowed freely across the surface.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s Shallow Radar (SHARAD) has peered deep into the northern ice cap and found layers of ice and sand buried beneath. The find adds nuance to the planet’s climate history, and reveals why some of the planet’s water remains locked in ice, instead of being lost to space.

Under the ice

Mars’ north polar region includes a site called the cavi unit, made up of ice and sand, buried underneath the more visible northern ice cap. SHARAD can peer up to a mile and a half into the ice, imaging the different layers. What it saw were alternating layers of sand and ice.

Researchers know that Mars, like Earth, wobbles on its orbit over tens of thousands of years. And as it wobbles, tilting toward or away from the Sun, the climate “wobbles” as well, growing warmer and cooler. So researchers think the ice in the cavi unit was laid down during colder, glacial periods on Mars. Previously, planetary scientists had assumed the ice would melt away during Mars’ warmer periods. But SHARAD revealed that the ice was instead covered over by sand, which insulated it from the Sun’s warm rays. This prevented it from melting away or being lost entirely, as much of Mars’ surface water was when its atmosphere thinned away.

Altogether the ice contained in the layers is one of the largest water reservoirs scientists have identified on the Red Planet, coming in just behind the ice caps themselves. If melted, the water contained in the subsurface layers could cover the planet to a depth of about five feet.

The research was led by Stefano Nerozzi from the University of Texas, who published his findings in Geophysical Research Letters on May 22. An additional study, published the same day, led by researchers from Johns Hopkins University, uses gravitational measurements, instead of radar, to confirm the findings.