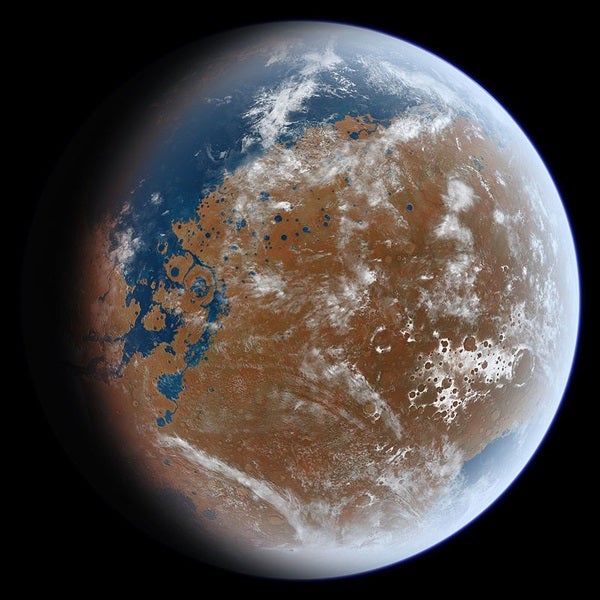

Scientists really want to learn what Mars ancient atmosphere was like in the past, as it could reveal a lot about what any hypothetical martian life would have been like. And now, according to a recent paper published in Nature Geoscience, researchers think one of Mars’ two puny moons could be key to unlocking the history of Mars’ primordial skies.

Phobos: A possible piece of the puzzle

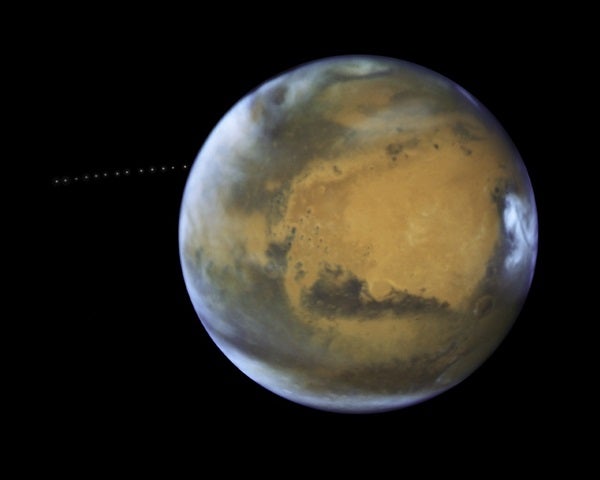

Mars’ moon Phobos orbits the Red Planet 60 times closer than our Moon orbits Earth. And such a tight orbit means it’s entirely feasible that Phobos has been hit by particles shed from Mars over time, leaving clues to the planet’s past atmosphere ingrained in Phobos’ surface.

That’s why, one day over coffee, Andrew Poppe — a research scientists at the Space Science laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-author of the new study — asked if anyone had considered what Phobos could tell scientists about Mars. Surprisingly, he learned, nobody had ever looked into it before.

The idea of using a moon, like Phobos, as a proxy for a planet’s past isn’t unheard of, though. Earth’s Moon is considered one of the best archives available for the early solar system thanks to its lack of atmosphere, wind, and water.

“What we’ve seen in Apollo samples is that the Moon has been patiently recording individual atoms coming from the Sun and from Earth,” Poppe said in a press release. “It’s a really cool historical record.”

So, using data from NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) spacecraft, Poppe, along with the study’s lead author, Quentin Nénon, a researcher at the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, looked into the possibility that Phobos held a similar historical record of Mars.

They found that a coating of such particles should be implanted into the small moon’s surface down to a depth of only some several hundred nanometers, or around 250 times shallower than the width of a human hair. However, they argue that’s still enough that any mission sent to the moon would easily be able to collect potential samples.

And as luck would have it, a mission to visit Phobos is already in the works.

MMX prepares to visit Mars’ moons

Phobos, along with its smaller sibling moon Deimos, are interesting to astronomers for more than just potential clues about Mars’ ancient atmosphere. Namely, scientists don’t know where the two moons came from in the first place. There are a few possibilities, ranging from being captured satellites to the spawns of the cloud of material Mars itself initially emerged from. But the mystery still remains unsolved.

Fortunately, to help determine the origin of at least one of Mars’ moons, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has plans to send a probe to Phobos. The craft, known as the Martian Moons Exploration (MMX), will be the first mission to collect samples from the surface of Phobos and deliver them back to Earth for further study. And based on this latest research, astronomers now suspect MMX may reveal more than just the origins of the martian moon.

“With a sample from the nearside,” said Nénon, “we could see an archive of the past atmosphere of Mars in the shallow layers of grain, while deeper in the grain we could see the primitive composition of Phobos.”

However, the key to such information would be for MMX to land on the nearside of Phobos, or the face that’s permanently facing Mars. (Like for Earth’s Moon, the differences between the nearside and the farside

can be vast). As Phobos is tidally locked to Mars, its nearside would have been bathed in ions for millennia, receiving some 20 to 100 times more particles than its farside.

MMX is currently slated to launch sometime in 2024 and arrive at Mars in 2025. The spacecraft would then return to Earth by 2029, carrying a load of Phobos samples. JAXA has yet to officially decide where MMX will land, though. “So hopefully,” Nénon said, “this finding will have an impact on the scientific activities of the MMX mission.”