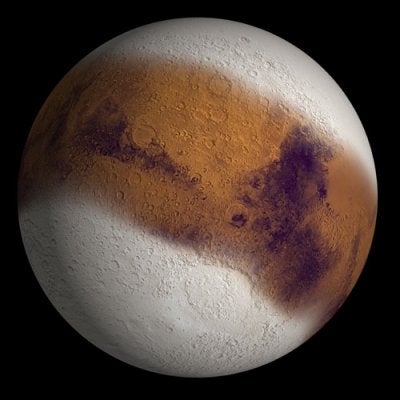

Spacecraft observations of Mars show different physical properties of layers in a region called Terra Meridiani. These differences suggest that the environment on this part of Mars varied through time as these layers were formed. Credit: NASA / JPL / Arizona State University.

Andrew Fazekas is an astronomy columnist based in Montreal, Canada, who frequently writes for magazines, newspapers, and the Canadian Space Agency. He currently does science news commentary for both radio and television, teaches backyard astronomy at Vanier College, and is an editor at the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Search for other articles by this author

Just as an armada of probes is beginning an assault on the Red Planet, scientists have upped the ante for finding convincing evidence for similarities between our world and it. The latest findings from NASA’s Mars Odyssey and Global Surveyor orbiters indicate the seemingly dry and dusty world may have recently climbed out of the grips of a true ice age. No woolly mammoths or rhinos accompanied a martian ice age, but with a familiar-sounding climate change and fresh discoveries of water-carved gullies, glacier-like flows, and buried ice, Mars may be more Earth-like than we ever thought.

By combining the latest infrared satellite maps with known patterns of past changes in Mars’ orbit and tilt, a team of American and Ukrainian geologists believes the Red Planet may have been frozen in a geologically recent ice age just 400,000 to 2.1 million years ago. The proof appears to lie in layers upon layers of distinctly different rock deposits scattered from mid-latitudes to the poles that point to a variation in the environment through time as each layer formed.

Reporting their results in the December 18 issue of the journal Nature, the authors argue that, just like on Earth, variations in the obliquity of Mars’ axis drives large-scale changes in climate. While Earth’s axial tilt has only varied between 22 to 24.5 degrees in the past 10 million years, Mars has experienced a more extreme wobble, ranging from 14 to 48 degrees.

This epoch of higher tilt is suggested to be the very driver for inducing ice ages on Mars that brought the distribution of water-ice from the polar regions down to mid-latitudes equivalent to southern United States and Saudi Arabia here on Earth. As the maritan poles warmed, water vapor formed and crept to the southernly latitudes where they got dumped as ice water mixed with dust. Glaciers may have overrun Mars of the past. Now, in a warmer, interglacial period, this thick deposit is in the process of degrading and retreating.

“These results show Mars is not a dead planet, but it undergoes climate changes that are even more pronounced than on Earth,” says team leader James Head of Brown University.

This research bodes well for NASA and their ‘follow-the-water’ strategy for Mars exploration. “The extreme climate changes on Mars are providing us with predictions we can test with upcoming Mars missions, such as Europe’s Mars Express and NASA’s Mars Exploration Rovers,” explains team member and Brown scientist John Mustard.

With a sensitive climate so similar to that of the Earth, hopes have been raised that our neighboring planet may indeed hold promise of present-day water. “Among the climate changes that occurred during these extremes is warming of the poles and partial melting of water at high altitudes,” Mustard continues. “This clearly broadens the environments in which life might occur on Mars.”