So perhaps it should seem fitting that the mountain is also home to the most powerful telescopes on the planet. But not everyone thinks so — the state’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) has sued NASA and the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy (IfA), insisting that cultural and environmental impact statements be completed before any new telescopes are built.

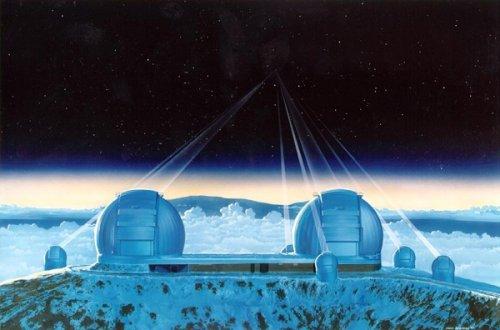

The instruments at the heart of the controversy are four to six 1.8-meter telescopes proposed by NASA that would flank the existing twin 10-meter Keck I and Keck II telescopes. These “outrigger” telescopes would be linked to the Kecks, collectively acting as a single large telescope (or interferometer), and would help researchers find and characterize extrasolar planets.

The outriggers, originally slated to cost $50 million dollars and to begin operating this year, are now on hold indefinitely, pending resolution of the lawsuit and a state permit hearing that will begin February 10.

While an environmental impact assessment was done for the planned outriggers, the OHA is suing for a more formal “Environmental Impact Statement” as outlined in the National Environmental Policy Act.

In a scathing complaint filed last April, the OHA writes: “Ironically, in their zeal to discover other life in the universe, the IfA and NASA are ignoring life on these islands … fixing their gaze on distant stars, the astronomers fail to see what is right before their eyes: the irreplaceable cultural and natural resources of Mauna Kea.”

According to the complaint, those resources include three cinder cones surrounded by at least 40 shrines that form the border of a “god/spirit zone at the summit of Mauna Kea,” and the Wekiu bug, an endemic species that has been nearly decimated. In addition, environmentalists worry about potential chemical spills and waste water mismanagement on the summit.

Tensions between native Hawaiian groups and the astronomical community have reached a fever pitch over use of the land, which is leased by the University of Hawaii and administered by its newly established Office of Mauna Kea Management.

“The telescope industry has actually changed the shape of the mountain in creating platforms,” says a member of the environmental group KAHEA who prefers not to be named. “It’s a visual invasion that seems intrusive and insulting because this wasn’t done in consultation with any Hawaiian people.”

“[Mauna Kea] is sacred to all of Polynesia and considered to be the birthplace of the gods — the analogy to Christians is where Jesus was born,” the KAHEA source continues. “Without question, it’s the most sacred place in all of Hawaii; that’s the beginning of our people.”

Bill Stormont, director of the Office of Mauna Kea Management, agrees. “It has extremely important spiritual significance to a large population of Hawaiians, myself included,” he says. “[Traditionally], only a very special few were allowed to go to the dominion of the gods. Members of the priesthood would have made pilgrimages to the mountain to gather spiritual wellness.”

He says the hundreds of stone piles on the summit may have astronomical significance in their arrangement, or may have been used ceremonially by families with ancestral ties to the mountain. Research suggests that from the 1100s to the 1700s, artisans fashioned tools from high-quality stone produced from a quarry near the peak. “There’s been pilfering of cultural resources on the mountain,” Stormont says. “A lot of the remnants of these workshops have been stolen.”

But, he says, “we now have rangers on the mountain to inform visitors and to make sure inappropriate behavior isn’t being done. As time goes by, those kinds of things are going to help demonstrate to the community that the university is going to take care of this place.”

Money is another thorny issue. “There’s a lot of questions people have over the exchange of money,” says the KAHEA source. An online document from KAHEA states, “Residents of Hawaii do not benefit at all from the millions of dollars in revenues generated by the observatories through renting out viewing time.”

But Stormont corrects this misperception. “Money isn’t being made by the telescopes,” he says. Researchers submit proposals to use the telescopes, but do not pay for it, the cost being absorbed by the organizations that maintain the observatories. “The telescopes bring, in some cases, huge staffs that live and work here; many of them are from these islands. It has a tremendous positive impact on the economy,” he says.