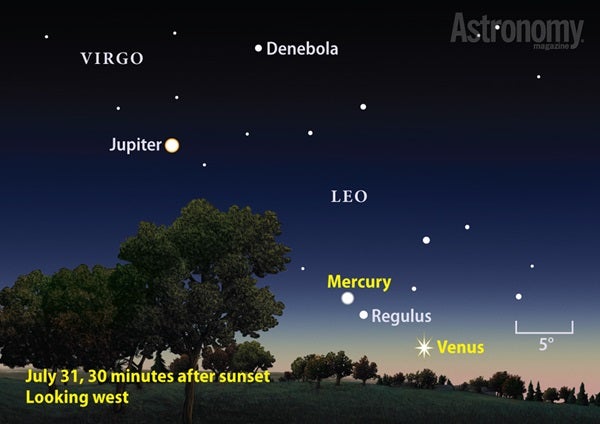

Mercury and Venus are among the more challenging of the solar system objects. Both scrape the western horizon during twilight in the latter half of July. Mercury passes behind the Sun on July 6 and then climbs slowly into view. It slides 0.5° north of Venus on the 16th, but the two are hopelessly lost in the Sun’s glare.

Your first realistic chance to find the duo comes July 21. Although Venus then lies just 2° high a half-hour after sunset, it shines brilliantly at magnitude –3.9. Mercury stands 3° to Venus’ upper left, but is harder to see because it glows more faintly, at magnitude –0.6. Binoculars will help pull them out of the twilight.

As Mercury ascends during the next 10 days, it also fades. On the 31st, it glows at magnitude –0.2 and stands 6° high 30 minutes after sundown. Bright Venus remains easier to see despite lying deeper in twilight.

By the time Mercury and Venus slip below the horizon, Jupiter comes to the fore. Unlike its siblings, however, the giant planet is an evening fixture throughout July. On the 1st, it lies 25° high in the west an hour after sunset and doesn’t set until midnight local daylight time. Gleaming at magnitude –1.9, Jupiter is unmistakable. Its altitude drops during July, and by month’s end it appears just 10° high an hour after sundown.

The best time to view Jupiter through a telescope is when it lies high in the sky in early July. Its slightly flattened disk then measures 34″ across and should show a wealth of atmospheric features.

You’ll find Mars due south and about one-third of the way to the zenith as darkness falls in early July. The planet shines brightly at magnitude –1.4, but stands out nearly as much for its distinctive orange-red hue. You can find it among the background stars of southern Libra, though Mars makes a better guide to the constellation’s faint outline than vice-versa.

The Red Planet reached opposition and peak visibility in late May and now is moving away from Earth. As a result, it fades by nearly 40 percent (to a still-bright magnitude –0.8) during July.

Mars’ increasing distance also reveals itself in the planet’s dwindling size. Point your telescope at Mars in early July and you’ll see a disk that spans an impressive 16″. Do the same thing at month’s end and you’ll encounter a 13″-diameter disk. But don’t fret: That’s plenty big enough to show subtle surface features if you view when Mars lies highest in the sky an hour or two after sunset. The greater altitude means you’ll be looking through less of Earth’s image-distorting atmosphere.

Summer ends in Mars’ northern hemisphere in early July, so the north polar ice cap should be near its minimum extent. Look for a patch of white — the permanent cap of water ice — near the planet’s northern limb. This region remains on view all month because the planet’s north pole currently tilts about 15° toward Earth. More subtle dark markings come and go as Mars rotates. The most conspicuous such feature — Syrtis Major — appears near the center of the planet’s disk during the evening hours in late July for North American observers.

Trailing about an hour behind Mars, Saturn also dazzles. The ringed planet reached opposition in early June and, like Mars, recedes from Earth during July. But unlike its closer cousin, Saturn shows little ill effect. Because the gas giant lies more than 10 times farther away, the percentage change doesn’t amount to much. Saturn dims from magnitude 0.1 to 0.3 during July, a barely noticeable difference.

Any telescope reveals Saturn’s globe, which measures 18″ across in mid-July, surrounded by a stunning ring system that spans 41″. The rings tilt 26° to our line of sight, just 1° less than the maximum they’ll achieve next year. Can you spot the outer A ring peeking above Saturn’s north pole? Or what about Saturn’s disk shining through the Cassini Division — the dark gap that separates the A ring from the brighter B ring?

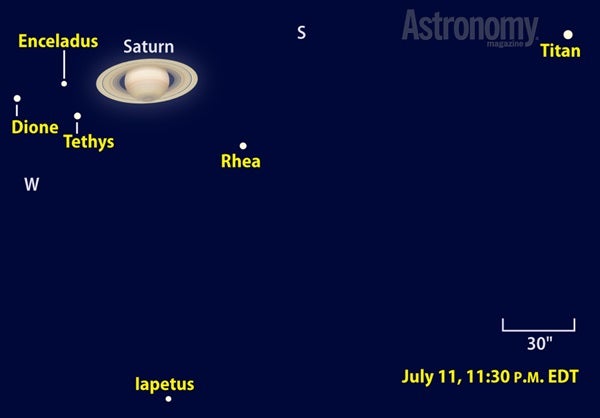

For small telescope owners, Saturn boasts more visible moons than mighty Jupiter, though none glows as brightly. The most obvious saturnian satellite is 8th-magnitude Titan. It takes 16 days to circle the planet, so you can see nearly two complete orbits during July. You’ll find this moon due north of Saturn on July 7 and 23 and due south of the planet July 15 and 31. It retreats up to 3.2′ away at greatest eastern and western elongation.

Outermost Iapetus spends most of its 79-day orbit far from Saturn. It slides 2.2′ due north of the planet the night of July 11/12, when it shines at 11th magnitude. By month’s end, it lies 8.4′ east of Saturn and its darker hemisphere faces Earth, so it glows dimly at 12th magnitude.

Three 10th-magnitude moons hover near Saturn like fireflies next to a bright light. All circle the planet in less than a week — Tethys in 1.9 days, Dione in 2.7 days, and Rhea in 4.5 days — and none strays more than 1′ from the edge of the rings.

Inner Enceladus proves more challenging because it glows dimly (12th magnitude) and stays close to the bright rings. It scoots around Saturn in 33 hours, so once you’ve spotted it, you can see it move noticeably in a few hours. Search for Enceladus near greatest elongation. A good opportunity comes the evening of July 11 when it lies 35″ west of Saturn and appears in a tight triangle with Tethys and Dione. Coincidentally, this is the same night Iapetus passes north of the ringed world.

Neptune rises shortly before midnight July 1 and two hours earlier by month’s close. It has a convenient guide star in 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii. Once you locate this star with binoculars, magnitude 7.8 Neptune will be in view as well. The planet begins the month 29′ (about a Full Moon’s diameter) southeast of Lambda and tracks slowly southwest. It passes 31′ due south of the star July 24/25. A telescope shows Neptune’s 2.3″-diameter disk and distinct blue-gray color.

On the night of July 22/23, the waning gibbous Moon passes in front of (occults) Neptune for those in most of eastern North America. The faint planet will be hard to see when it disappears behind our satellite’s bright limb, but much easier when it reappears next to the dark limb. For locations south and east of northern New Mexico, the Moon also occults Lambda Aquarii. Exact times depend on your location. For specifics, go to www.lunar-occultations.com.

Uranus rises about 90 minutes after Neptune, so by July’s final week, it pokes above the horizon before midnight and completes our tally of eight evening worlds. Uranus resides among the background stars of Pisces the Fish, southeast of the Great Square of Pegasus.

To find the planet through binoculars, first center magnitude 4.8 Mu (μ) Piscium in the field of view. Some 2° to 3° north of Mu lies a group of four 6th-magnitude objects. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is the brightest and northernmost of this quartet. The planet doesn’t move much relative to the background stars during July, remaining some 2.7° north of Mu. To confirm a sighting, point your telescope at what you think is Uranus. Only the planet will show a distinctive blue-green disk spanning 3.5″.

The last major event this month occurs the morning of July 29 when the waning crescent Moon occults Aldebaran. With the Moon just 23 percent lit and the star shining at 1st magnitude, even Aldebaran’s disappearance behind Luna’s bright limb should be easy to view. Observers south of a line running from southern New Mexico to northern Maine should see the event while those to the north will see the Moon and star just miss.

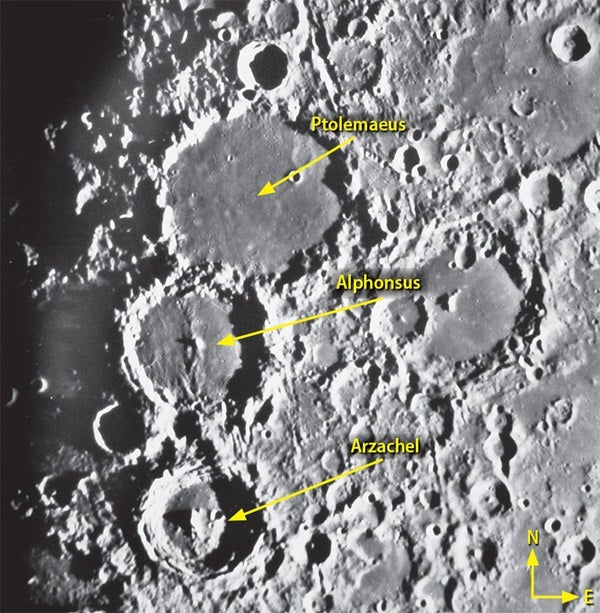

Reminiscent of seasonal changes in Earth’s polar regions, the lunar north transforms every month from creeping cratered shadows to a sprawling reflective domain and back again. On July 19, the high Sun at Full Moon reveals a zone with gray patches and white rays that converge toward the youthful crater Anaxagoras.

The progression begins on the 12th, an evening after First Quarter phase. First locate Goldschmidt, a 75-mile-wide crater that sports a freckled floor and a low rim. Relentless bombardment from solar system debris has worn down its once-steep walls and left rounded shadows that extend across the shallow floor. The crater got its name from a 19th-century German amateur astronomer.

Return to the area one evening later when sunlight has advanced to the sharp-rimmed Anaxagoras. This crater’s deep floor remains in shadow on both the 13th and 14th (the top photo approximates the second day). Notice how this 32-mile-wide feature cuts into the edge of sprawling Goldschmidt. As Full Moon approaches, watch Anaxagoras turn into the brightest splotch of rays in the north.

The younger crater, named after a Greek philosopher, and Tycho, in the south, are of a similar age. If Anaxagoras were closer to the equator, it would be just as famous as Tycho. The rays spread evenly and are beautifully defined at Full Moon when the debris apron almost obscures its older neighbor, Goldschmidt.

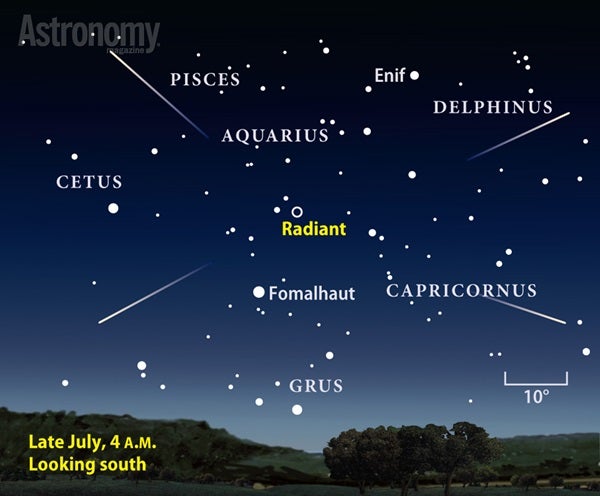

In terms of volume, few meteor showers can compete with the Southern Delta Aquariids. Unfortunately, the shower’s peak is so broad that a viewer typically sees only a modest number of “shooting stars.” The shower peaks the night of July 29/30, though you’ll probably see just as many meteors a day or two on either side.

The streaks of light appear to radiate from near 3rd-magnitude Delta (δ) Aquarii, which climbs highest around 3 a.m. local daylight time. From the Southern Hemisphere, where the radiant passes nearly overhead, observers can see up to 16 meteors per hour. Those at mid-northern latitudes will be lucky to see half that number.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (west) |

Mars (southwest) |

Uranus (southeast) |

| Venus (west) |

Saturn (southwest) |

Neptune (south) |

| Mars (south) |

Neptune (southeast) |

|

| Jupiter (west) |

||

| Saturn (south) | |

|

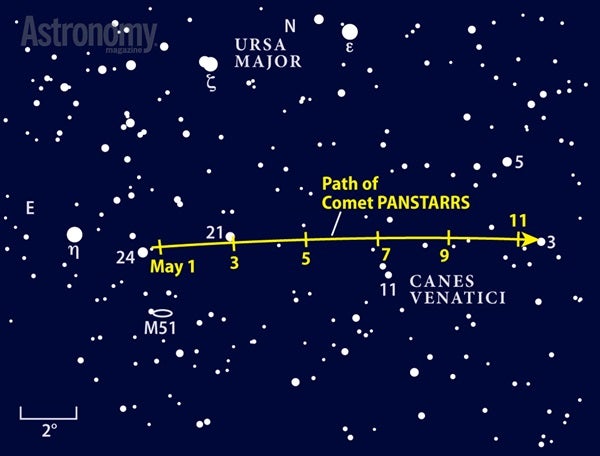

July’s brightest comet lurks low in the south during early evening. To avoid bright moonlight, hunt down Comet PANSTARRS (C/2013 X1) either at the beginning or end of the month. The dirty snowball should glow at 6th magnitude in early July, one or two magnitudes brighter than it will be by month’s end. It should be easier to see late in the month, however, because it lies higher in the sky.

For observers in the northern United States and Canada, PANSTARRS will be hard to see as it skims south of Scorpius in early July. In the month’s final 10 days, it makes its way through northern Centaurus, passing 0.6° west of magnitude 4.1 c1 Centauri on the 23rd. C/2013 X1 should be visible through binoculars then, though barely, and a nice target for small telescopes.

The comet should appear as an out-of-round gray fuzzball. To see more detail, bump up the power. Notice that the northwestern edge looks sharper because that’s where the solar wind of charged particles flows past the comet. Large scopes may show a hint of green from escaping gases. And if PANSTARRS ejects a decent amount of dust, you might see a stubby tail pointing to the southeast.

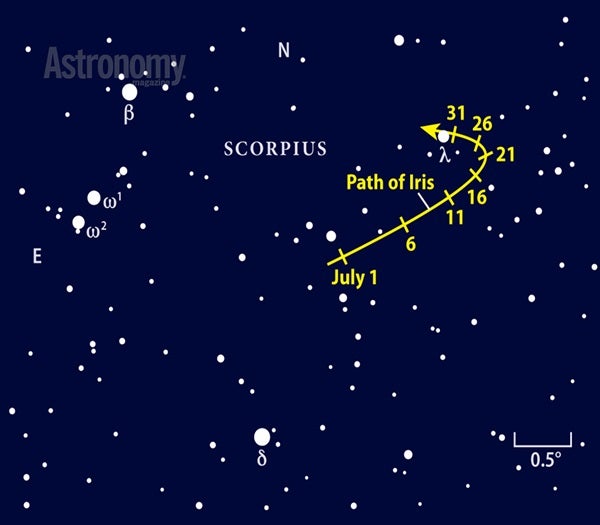

Luck plays into our hands this month because asteroid 7 Iris lies just about midway between Mars and Saturn. Before you track down Iris, however, take a moment to enjoy the easy double star Beta (β) Scorpii. Even the smallest scope at low power will split the pretty blue-white components, which shine at magnitudes 2.6 and 4.9 with a separation of 14″. Iris lies 2° to 3° west-southwest of the star, a pale white dot in comparison.

To track down the 10th-magnitude asteroid, use the brighter stars to create a memorable pattern in your mind and then zero in on the spot where the map below shows Iris to be. There’s not much of similar brightness nearby, particularly in July’s last 10 days. On the month’s final night, the asteroid approaches within 5′ of magnitude 5.0 Lambda (λ) Librae.

If you’re a stickler for proof, Iris itself provides confirmation by moving slowly relative to the background stars from night to night. Make a sketch of the field of view about a Moon-diameter across, placing a half-dozen dots as best as you can. Remember to note which edge of your sketch is north by nudging the scope up toward Polaris and seeing where new stars appear in the field. Then come back a night or two later and see which of the dots has shifted position — that will be Iris.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.