Key Takeaways:

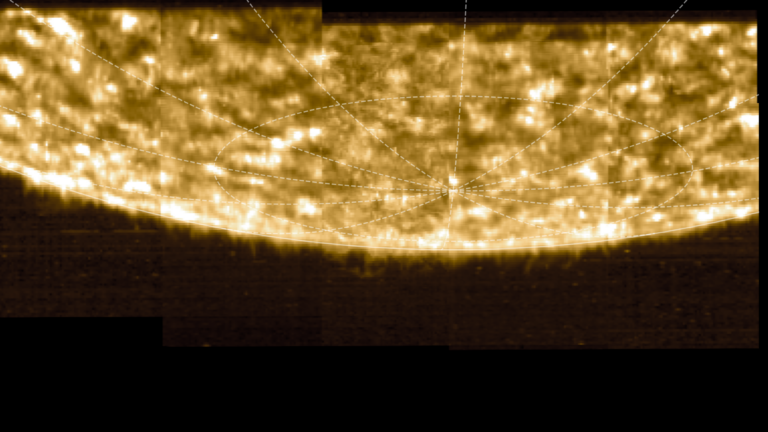

Mercury does not rotate on its axis smoothly, like a record, but experiences regular fluctuations in speed over an 88-day cycle — a year on the closest planet to the Sun. These oscillations, or librations, are caused by the planet’s interactions with the Sun as it moves around the star. The Sun’s gravitational pull speeds up or slows down Mercury’s rotation depending on where the oblong-shaped planet is on its elliptical orbit.

Scientists can use measurements of Mercury’s rotation and its librations to infer information about the interior of the planet, said Alexander Stark from the German Aerospace Center at the Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin.

The new study details new measurements of Mercury’s movements taken by the MESSENGER spacecraft, which orbited the planet for more than four years before its propellant was exhausted and it purposefully crash-landed on Mercury in April 2015. Scientists had measured Mercury’s librations from Earth, but the new measurements from MESSENGER are the first taken while orbiting Mercury, providing a new way to measure the planet’s oscillations.

The new measurements show that Mercury is spinning on its axis about nine seconds faster than scientists had previously calculated. “It is not a huge difference, parts per million, but it is unexpected,” said Jean-Luc Margot from the University of California, Los Angeles.

The scientists think the difference in rotational speed could come from Jupiter’s large gravity field tugging on Mercury’s orbit, changing the planet’s distance to the Sun and the star’s influence on its spin. The authors of the new study propose that Jupiter, which travels around the Sun roughly once every 12 years, has superimposed a 12-year long-term libration on top of Mercury’s 88-day libration. This long-term libration could be causing the slight increase in speed observed during the time period of the new study and also cause a slowdown in Mercury’s spin at other times, according to the study’s authors.

Margot said the influence of Jupiter on Mercury is only one possible explanation for the new observations, and additional measurements could unveil additional influences on the planet. The European Space Agency’s BepiColombo mission to Mercury launching in 2017 may be able to answer some of these questions, according to the study’s authors.

“It’s still a bit of a puzzle,” Margot said.

The new study also found that when Mercury starts to revolve farther from the Sun and the Sun starts to slow Mercury’s rotation, the planet rotates 1,500 feet (460 meters) short of its full rotation — a distance equivalent to the height of the Empire State Building. As it circles closer to the Sun, the planet speeds up and makes up the lost distance.

These new measurements, which agree with Earth-based measurements, show that Mercury’s libration is about twice as big as would be expected if the planet were entirely solid, said Margot. This confirms the theory that Mercury has a liquid outer core, an idea put forth by studies using Earth-based measurements of Mercury’s spin.

If a planet has a molten outer core, the planet’s outer and inner layers are not locked together. The outer layers — the crust and the mantle — can experience large librations in response to the gravitational pull from the Sun.

The new measurements should help scientists model Mercury’s interior, said Stark.