The work led by Caroline Foster of the Australian Astronomical Observatory has used the Umbrella Galaxy (NGC 4651) to reveal insights in galactic behavior.

Astronomy magazine has teamed up with Emmy Award-winning artist Jon Lomberg to offer Galactic Tidal Star Streams. This poster is the first and only artwork showing galactic tidal star streams, which occur as larger galaxies rip stars away from smaller ones and consume them. You can get this 16” x 20” print at MyScienceShop.com today!

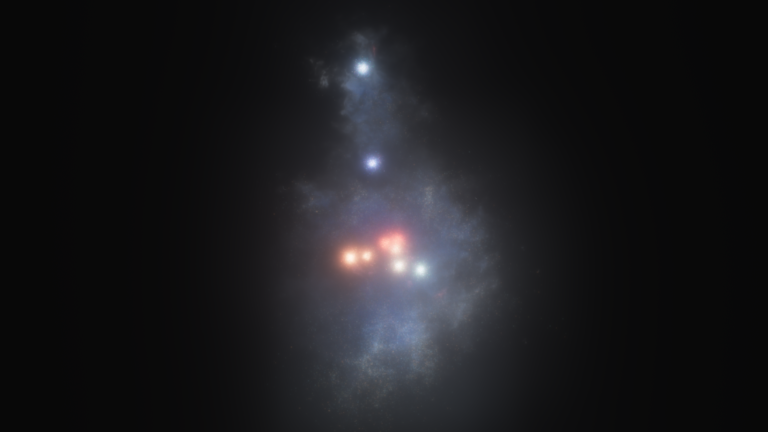

The merging of small galaxies into larger ones is common throughout the universe, but because the shredded galaxies are so faint, it has been hard to extract details in 3-D about how such mergers proceed. Using the most powerful optical facilities in the world, the twin 10-meter Keck Observatory and the 8-meter Subaru Telescope near the summit of Mauna Kea, Foster and her collaborators have determined enough about the character of the merger to provide a detailed model of how and when it occurred.

After taking panoramic images of the Umbrella with Suprime-Cam on Subaru, the scientists used the DEIMOS instrument, installed on the Keck II Telescope, to map out the motions of the stream and determine how the galaxy is being shredded.

The stars in the stream are incredibly faint, so it was necessary to use a proxy technique to measure the speeds of brighter tracer objects moving along with the stream stars. These bright tracers include globular star clusters, planetary nebulae — dying stars that glow like neon lights — and patches of glowing hydrogen gas.

“This is important because our whole concept about what galaxies are and how they grow has not been fully verified,” said Aaron Romanowsky from both San José State University and the University of California Observatories. “We think they are constantly consuming smaller galaxies as part of a cosmic food chain, all pulled together by a mysterious form of invisible ‘dark matter.’ When a galaxy is torn apart, we sometimes get a glimpse of the hidden vista because the stripping process lights it up. That’s what occurred here.”

“Through new techniques, we have been able to measure the movements of the stars in the very distant, very faint stellar stream in the Umbrella,” Foster said. “This allows us for the first time to reconstruct the history of the system.”

“Being able to study streams this far away means that we can reconstruct the assembly histories of many more galaxies,” Romanowsky said. “In turn, that means we can get a handle on how often these ‘minor mergers,’ thought to be an important way that galaxies grow, actually occur. We can also map out the orbits of the stellar streams to test the pull of gravity for exotic effects, much like the Moon going around the Earth but without having to wait 300 million years for the orbit to complete.”

The present work is a follow-up to a 2010 study led by David Martínez-Delgado from the University of Heidelberg, which used small robotic telescopes to image eight isolated spiral galaxies and found the signs of mergers — shells, clouds, and arcs of tidal debris — in six of them.