After MESSENGER completed its successful flyby of Mercury, the Narrow Angle Camera (NAC), part of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), took images of the receding planet. Beginning on January 14, 2008, about 100 minutes after MESSENGER’s closest pass by the surface of Mercury, until January 15, 2008, about 19 hours later, the NAC acquired one image every four minutes. In all, 288 images were snapped during this sequence; shown here are just 12 of those departing shots.

This large set of departing NAC images has been assembled into a movie, which will be shown today during a NASA press conference at 1 pm EST.

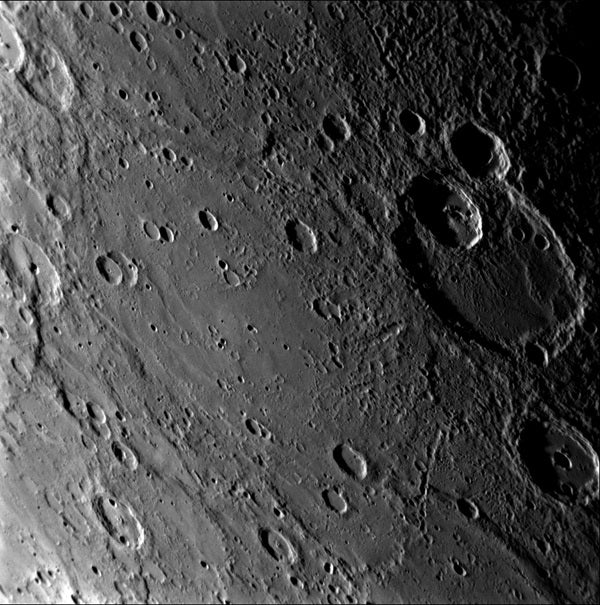

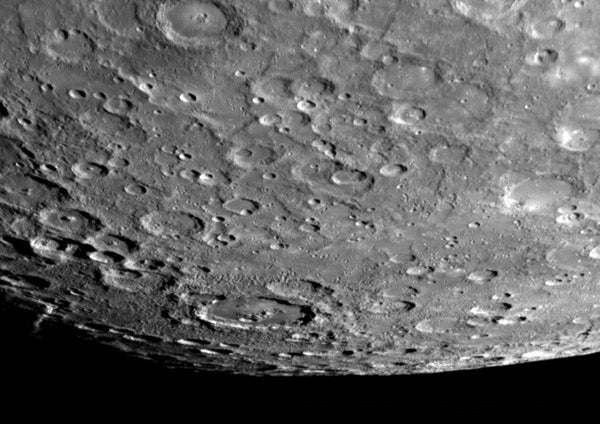

As the MESSENGER team continues to study the high-resolution images taken during the Mercury flyby encounter on January 14, 2008, scarps (cliffs) that extend for long distances are discovered. This frame, taken by the Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), shows a region of Mercury’s surface previously unseen by spacecraft and a large scarp crossing vertically through the scene, on the far right of the image. This scarp is the northern continuation of the one seen in the NAC image released on January 16.

The presence of many long and high scarps, as discovered from pictures from the Mariner 10 mission in 1974 and 1975, suggests a history for Mercury that is unlike that of any of the other planets in the solar system. These giant scarps are believed to have formed when Mercury’s interior cooled and the entire planet shrank slightly as a result. However, Mariner 10 was able to view less than half the planet, so the global extent of these scarps has been unknown. MESSENGER images, like this one, are providing the first high-resolution looks at many areas on Mercury’s surface, and science team members are busy mapping these newly discovered scarps to see whether they are common everywhere on the planet.

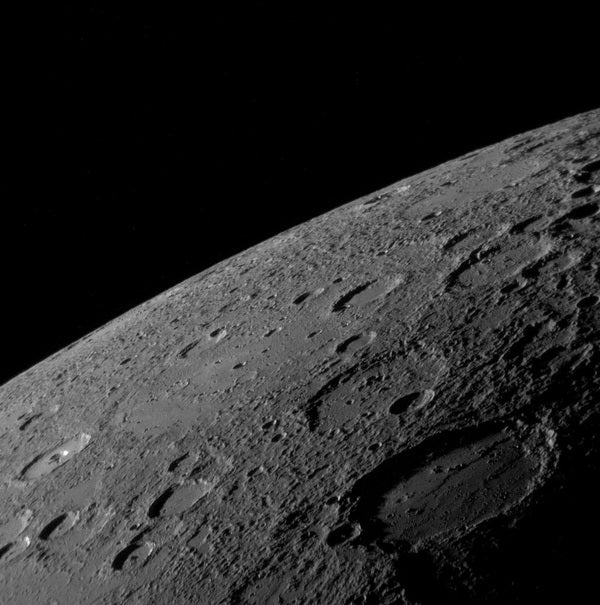

As MESSENGER sped by Mercury on January 14, 2008, the Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) captured this shot looking toward Mercury’s north pole. The surface shown in this image is from the side of Mercury not previously seen by spacecraft. The top right of this image shows the limb of the planet, which transitions into the terminator (the line between the sunlit, day side and the dark, night side) on the top left of the image. Near the terminator, the Sun illuminates surface features at a low angle, casting long shadows and causing height differences of the surface to appear more prominent in this region.

It is interesting to compare MESSENGER’s view to the north with the image looking toward the south pole, released on January 21. Comparing these two images, it can be seen that the terrain near the south pole is more heavily cratered while some of the region near the north pole shows less cratered, smooth plains material, consistent with the general observations of the poles made by Mariner 10. MESSENGER acquired over 1200 images of Mercury’s surface during its flyby, and the MESSENGER team is busy examining all of those images in detail, to understand the geologic history of the planet as a whole, from pole to pole.

During MESSENGER’s flyby of Mercury on January 14, 2008, part of the planned sequence of observations included taking images of the same portion of Mercury’s surface from five different viewing angles. The first view from this sequence was taken just after MESSENGER made its closest approach to Mercury, from a low viewing angle; an image of the first view was released on January 19. The image released here, acquired with the Wide Angle Camera (WAC) on the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), was snapped 13 minutes after MESSENGER’s closest approach with Mercury. The lower two-thirds of this image shows much of the same terrain seen in the first view, but from a much higher viewing angle, as the spacecraft began to pass nearly overhead. At the time of this image, MESSENGER was at a distance of about about 2000 miles (3000 kilometers) from Mercury.

A comparison of the images taken at different viewing angles provides important information about the properties of the materials that make up Mercury’s surface. In addition, each view was taken through all 11 of the WAC’s narrow-band color filters. The image shown here is from filter 7, which is sensitive to light near the red end of the visible spectrum (750 nm). The MESSENGER team is working to compare these images taken from different perspectives and in different colors to understand surface properties on Mercury. In addition, knowledge of the variation of image properties with viewing angle in this region will permit a more confident comparison of images of other portions of the surface taken at different illumination and viewing angles.

See Mercury through the “eyes” of MESSENGER’s imagers with the Mercury Flyby Visualization Tool. This new web feature offers a unique opportunity to see simulated views of Mercury from MESSENGER’s perspective during approach, flyby, and departure, or in real-time (as the observations actually occur).

This tool combines the best available image map of Mercury’s surface with observation sequences for the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer (MASCS), and Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA). The map of Mercury’s surface combines Earth-based low-resolution radar images from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and image mosaics from the Mariner 10 spacecraft flybys of Mercury in 1974 and 1975.

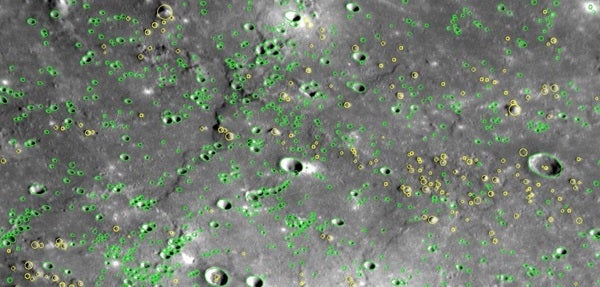

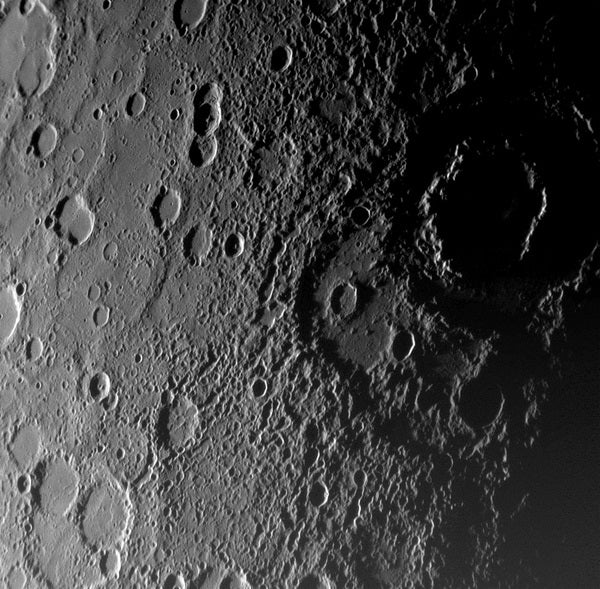

On January 14, 2008, MESSENGER flew by Mercury and snapped images of a large portion of the surface that had not been previously seen by spacecraft. Ever since the first images were received back on Earth one day later, January 15, MESSENGER team members have been closely examining and studying this “new” terrain with great interest and excitement.

One of many investigations underway includes identifying and measuring the impact craters on these previously unseen regions. The density of craters on the surface of a planet can be used to indicate the relative age of different places on the surface; the more craters the surface has accumulated, the older the surface. By counting craters on different areas of Mercury’s surface, a relative geologic history of the planet can be constructed, indicating which surfaces formed first and which formed later. However, this process is also time consuming; Mercury has a lot of craters!

Of course, simply counting the craters is not enough. Each crater has to be measured and classified to fully interpret the differences in crater density. Many small craters form as “secondaries,” as clumps of material ejected from a “primary” crater re-impact the surface in the regions surrounding the primary. In order to learn about the history of asteroid and comet impacts on Mercury, scientists have to distinguish between the primary and secondary craters. Once many more craters are measured, MESSENGER researchers will have new insights into the geological history of Mercury.

As the MESSENGER spacecraft approached Mercury on January 14, 2008, the Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) snapped this image of the crater Matisse. Named for the French artist Henri Matisse, Matisse crater was imaged during the Mariner 10 mission and is about 130 miles (210 kilometers) in diameter. Matisse crater is in the southern hemisphere and can be seen near the terminator of the planet (the line between the sunlit, day side and the dark, night side) in both the color and single-filter, black-and-white images released previously that show an overview of the entire incoming side of Mercury.

On Mercury, craters are named for people, now deceased, who have made contributions to the humanities, such as artists, musicians, painters, and authors. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) oversees the official process of naming new craters and other new features discovered on bodies throughout the solar system. Scientists studying and mapping unnamed features can suggest names for consideration by the IAU. The 1213 images taken by MESSENGER during its first flyby encounter with Mercury cover a large region of Mercury’s surface previously unseen by spacecraft, revealing many new craters and other features that will need to be named.

One week ago, the MESSENGER spacecraft transmitted to Earth the first high-resolution image of Mercury by a spacecraft in over 30 years, since the three Mercury flybys of Mariner 10 in 1974 and 1975. MESSENGER’s Wide Angle Camera (WAC), part of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), is equipped with 11 narrow-band color filters, in contrast to the two visible-light filters and one ultraviolet filter that were on Mariner 10’s vidicon camera. By combining images taken through different filters in the visible and infrared, the MESSENGER data allow Mercury to be seen in a variety of high-resolution color views not previously possible. MESSENGER’s eyes can see far beyond the color range of the human eye, and the colors seen in the accompanying image are somewhat different from what a human would see.

The color image was generated by combining three separate images taken through WAC filters sensitive to light in different wavelengths; filters that transmit light with wavelengths of 1000, 700, and 430 nanometers (infrared, far red, and violet, respectively) were placed in the red, green, and blue channels, respectively, to create this image. The human eye is sensitive across only the wavelength range 400 to 700 nanometers. Creating a false-color image in this way accentuates color differences on Mercury’s surface that cannot be seen in the single-filter, black-and-white image released last week.

Image sequences acquired through the 11 different MDIS filters are being used to distinguish subtle color variations indicative of different rock types. By analyzing color differences across all 11 filters, the MESSENGER team is investigating the variety of mineral and rock types present on Mercury’s surface. Such information will be key to addressing fundamental questions about how Mercury formed and evolved.

Mercury has a diameter of about 3030 miles (4880 kilometers), and the smallest feature visible in this color image is about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in size.

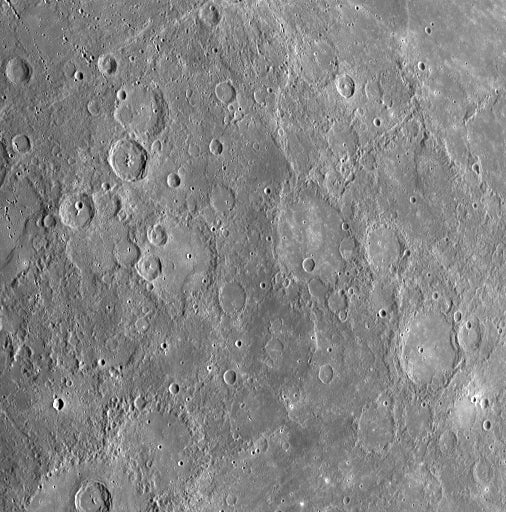

One week ago, on January 14, 2008, MESSENGER passed 124 miles (200 kilometers) above the surface of Mercury and snapped the first pictures of a side of Mercury not previously seen by a spacecraft. The image to the right shows that previously unseen side, with a view looking toward Mercury’s south pole. The southern limb of the planet can be seen in the bottom right of the image. The bottom left of the image shows the transition from the sunlit, day side of Mercury to the dark, night side of the planet, a transition line known as the terminator. In the region near the terminator, the sun shines on the surface at a low angle, causing the rims of craters and other elevated surface features to cast long shadows, accentuating height differences in the image.

This image is just one in a planned sequence of 42 images acquired by the Narrow Angle Camera of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS). From these 42 images, the MESSENGER team is creating a high-resolution mosaic image of this previously unseen portion of Mercury. During the flyby, MDIS took more than 1,200 images, which are being combined to create multiple mosaics with different resolutions and of different portions of the planet. The creation of high-resolution mosaic images will enable a global view of Mercury’s surface and will be used to understand the geologic processes that made Mercury the planet we see today.

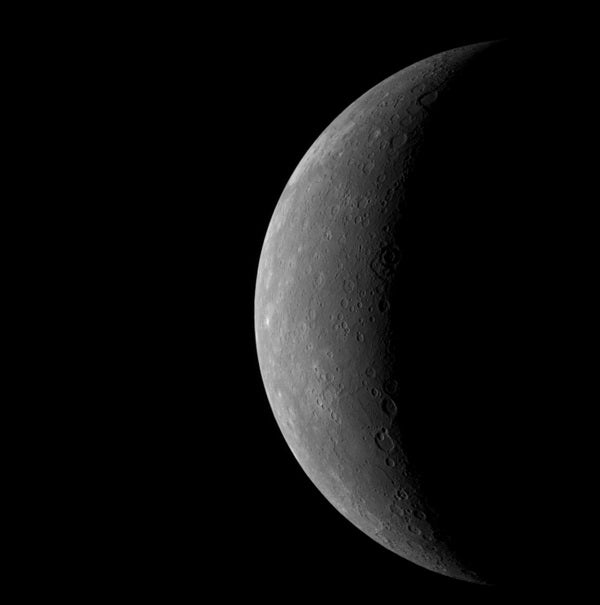

As MESSENGER neared Mercury on January 14, 2008, the spacecraft’s Wide Angle Camera on the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) took images of the planet through each of its 11 filters. This image of the planet’s full crescent was taken using the 7th filter, in light near the far-red end of the visible spectrum (750 nm). The image shows portions of Mercury previously seen by Mariner 10, but when Mariner 10 flew by the planet at each of its encounters the Sun was nearly overhead. For this MESSENGER flyby, in contrast, the Sun is shining obliquely on regions near the day/night boundary (called the terminator) on the right-hand side of the crescent, revealing the surface topography in sharp relief. This image illustrates how MESSENGER, during its future flybys and subsequent orbital mission, will teach us much about the portion of Mercury already imaged by Mariner 10, and not just because of its superior camera and close proximity to the planet. The solar lighting geometry makes an enormous difference.

A day after its successful flyby of Mercury, the MESSENGER spacecraft turned toward Earth on Tuesday and began downloading the 500 megabytes of data that had been stored on the solid-state recorder during the encounter. All of those data, including 1,213 images from the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) cameras, have now been received by the Science Operations Center at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. Preliminary analysis of these data by the MESSENGER Science Team has confirmed that all seven MESSENGER instruments are healthy and operated as planned during the flyby.

As MESSENGER flew by the planet, it missed its targeted aim point by only 5.12 miles (8.25 kilometers), affording the critical gravity assist needed to continue on a course to become, in 2011, the first spacecraft ever to orbit Mercury. During this first encounter, the payload successfully conducted a carefully orchestrated sequence of observations designed to take full advantage of the geometry of the flyby trajectory and to optimize the science return from each instrument.

In addition to images of the previously unseen portion of the planet’s surface, measurements were made that will contribute to the characterization of all aspects of Mercury and its environment, from its metallic core to the far reaches of its magnetosphere. “We have one excited science team,” says MESSENGER Project Manager, Peter D. Bedini, of APL, “and their enthusiasm is contagious.”

The analysis of these data is just beginning, but there are already indications that new discoveries are at hand.

As the MESSENGER spacecraft drew closer to Mercury for its historic first flyby, the spacecraft’s Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) on the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) acquired an image mosaic of the sunlit portion of the planet. This image is one of those mosaic frames and was acquired on January 14, 2008, when the spacecraft was about 11,000 miles (18,000 kilometers) from the surface of Mercury, about 55 minutes before MESSENGER’s closest approach to the planet.

This large 120 miles (about 200 milometers) crater was seen in less detail by Mariner 10 more than 3 decades ago and was named Sholem Aleichem for the Yiddish writer. In this MESSENGER image, it can be seen that the plains deposits filling the crater’s interior have been deformed by linear ridges. The shadowed area on the right of the image is the day-night boundary, known as the terminator. Altogether, MESSENGER acquired over 1200 images of Mercury, which the science team members are now examining in detail to learn about the history and evolution of the innermost planet.

As MESSENGER approached Mercury on January 14, 2008, the spacecraft’s Narrow-Angle Camera on the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) instrument captured this view of the planet’s rugged, cratered landscape illuminated obliquely by the Sun. The large, shadow-filled, double ringed crater to the upper right was glimpsed by Mariner 10 more than three decades ago and named Vivaldi, after the Italian composer. Its outer ring has a diameter of about about 125 miles (200 kilometers). MESSENGER’s modern camera has revealed detail that was not well seen by Mariner 10, including the broad ancient depression overlapped by the lower-left part of the Vivaldi crater. The MESSENGER science team is in the process of evaluating later images snapped from even closer range showing features on the side of Mercury never seen by Mariner 10. It is already clear that MESSENGER’s superior camera will tell us much that could not be resolved even on the side of Mercury viewed by Mariner’s vidicon camera in the mid-1970s.

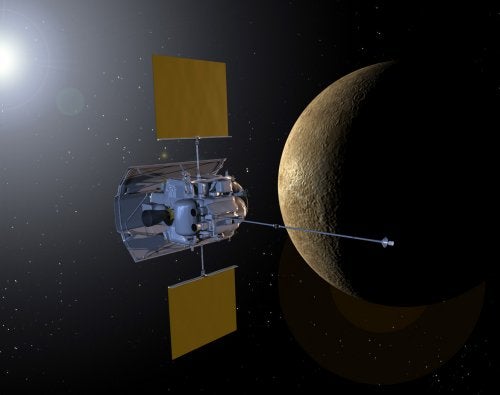

NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft is on track for its first flyby of Mercury today. The craft will explore the planet from as close as 125 miles (200 kilometers).

The MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) craft, launched August 3, 2004, will be the first spacecraft to study the innermost planet while in orbit around it. Following three flybys during the next 3 years, MESSENGER will reach orbit around Mercury in 2011.

Planetary scientists are eager to get a closer look at the Sun’s nearest neighbor.

“We are about to visit Mercury for the first time in more than 30 years, and we can’t wait,” says MESSENGER principal investigator Sean Solomon of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

NASA’s Mariner 10 is the only other spacecraft to visit the planet closest to the Sun.

“We’ll be making close-in observations of the composition of Mercury’s surface and atmosphere, and we’ll be probing deeper into the planet’s magnetosphere than we’ve ever been,” says Solomon.

The MESSENGER probe’s Mercury Dual Imaging System cameras began snapping pictures of the planet January 9. NASA plans a mission update on the Mercury flyby January 30.

Visit MESSENGER’s online newsroom.

On January 9, MESSENGER’s Mercury Dual Imaging System cameras began gathering pictures of Mercury as the probe zeros in on the planet.

“With just one week to go before the flyby, the spacecraft is on target to encounter the planet at an altitude of 202 kilometers,” says Mission Systems Engineer Eric Finnegan of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “All subsystems and instruments are operating nominally and configured for the start of the flyby sequence, except for the Mercury Laser Altimeter and part of the Gamma-Ray Spectrometer, which we’ll turn on just before the flyby.”

Over the next week, the team will make final flyby preparations and upload the final command sequences for the encounter.

“We are about to visit Mercury for the first time in more than 30 years, and we can’t wait,” says MESSENGER Principal Investigator Sean Solomon of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. “In addition to providing the critical gravity assist that will move MESSENGER along its path toward Mercury orbit insertion in March 2011, this flyby will let us see parts of Mercury never before viewed by spacecraft. We’ll be making close-in observations of the composition of Mercury’s surface and atmosphere, and we’ll be probing deeper into the planet’s magnetosphere than we’ve ever been. We expect many surprises.”

On December 19th, MESSENGER’s 19th trajectory correction maneuver (TCM-19) changed the spacecraft’s velocity by 3.6 feet per second (1.1 meters per second), directing MESSENGER closer to its intended target for the first flyby. TCM-19 went so well that the mission design and navigation teams have decided that a TCM scheduled for January 10 will not be needed.

“Cancellation of this maneuver is a demonstration of the near-perfect execution of TCM-19 just prior to the start of the holiday season,” says Finnegan.