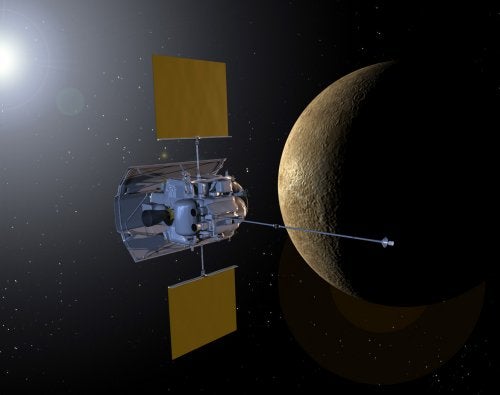

The first spacecraft designed by NASA to orbit Mercury is giving scientists a new perspective on the planet’s atmosphere and evolution.

Launched in August 2004, the MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging spacecraft, known as MESSENGER, conducted a third and final flyby of Mercury in September 2009. The probe completed a critical maneuver using the planet’s gravity to remain on course to enter into orbit around Mercury next year.

Data from the final flyby has revealed the first observations of ion emissions in Mercury’s exosphere, or thin atmosphere, new information about the planet’s magnetic substorms, and evidence of younger volcanic activity than previously recorded.

The distribution of individual chemical elements that the spacecraft saw in Mercury’s exosphere varied around the planet. Detailed altitude profiles of those elements in the exosphere over the north and south poles of the planet were also measured for the first time.

“These profiles showed considerable variability among the sodium, calcium, and magnesium distributions, indicating that several processes are at work and that a given process may affect each element quite differently,” said Ron Vervack from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

Emission from ionized calcium in Mercury’s exosphere was observed for the first time during the flyby. The emission was concentrated over a relatively small portion of the exosphere, with most of the emission occurring close to the equatorial plane.

During its first two flybys of Mercury, the spacecraft captured images confirming that the planet’s early history was marked by pervasive volcanism. The spacecraft’s third flyby revealed a new chapter in that history within an impact basin 180 miles (290 kilometers) in diameter that is among the youngest basins seen. The basin, recently named Rachmaninoff, has an inner floor filled with smooth plains that differ in color from their surroundings. These sparsely cratered plains are younger than the basin they fill and apparently formed from material that once flowed across the surface.

“We interpret these plains to be the youngest volcanic deposits we have yet found on Mercury,” said Louise Prockter of APL. “Other observations suggest the planet spanned a much greater duration volcanism than previously thought, perhaps extending well into the second half of solar system history.”

For the first time, the spacecraft revealed substorm-like build-up, or loading, of magnetic energy in Mercury’s magnetic tail. The increases in energy measured in Mercury’s magnetic tail were very large. They occurred quickly, lasting only 2 to 3 minutes from beginning to end. These increases in tail magnetic energy on Mercury are about 10 times greater than on Earth, and the substorm-like events run their course about 50 times more rapidly.

Magnetic substorms are space-weather disturbances that occur intermittently on Earth, usually several times per day and last from 1 to 3 hours. Earth substorms are accompanied by a range of phenomena, such as the majestic auroral displays seen in the Arctic and Antarctic skies. Substorms also are associated with hazardous energetic particle events that can wreak havoc with communications and Earth-observing satellites.

“The extreme tail loading and unloading observed at Mercury implies that the relative intensity of substorms must be much larger than on Earth,” said James A. Slavin from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The new measurements give fresh insight on the time duration of Mercury’s substorms. Scientists await more extensive measurements when the spacecraft is in orbit.

“Every time we’ve encountered Mercury, we’ve discovered new phenomena,” said Sean Solomon from the Carnegie Institution of Washington. “We’re learning that Mercury is an extremely dynamic planet, and it has been so throughout its history. After MESSENGER has been safely inserted into orbit around Mercury next March, we’ll be in for a terrific show.”

In addition to flying by Mercury, the spacecraft flew past Earth in August 2005 and Venus in October 2006 and June 2007. The NASA spacecraft has imaged approximately 98 percent of Mercury’s surface. After this spacecraft goes into orbit around Mercury for a yearlong study of the planet, it will observe the polar regions, which are the only unobserved areas of the planet.