NASA’s Mars Rover Opportunity is investigating a metallic meteorite the size of a large watermelon that is providing researchers more details about the Red Planet’s environmental history.

The rock, dubbed “Block Island,” is larger than any other known meteorite on Mars. Scientists calculate it is too massive to have hit the ground without disintegrating unless Mars had a much thicker atmosphere than it has now when the rock fell. Atmosphere slows the descent of meteorites. Additional studies also may provide clues about how weathering has affected the rock since it fell.

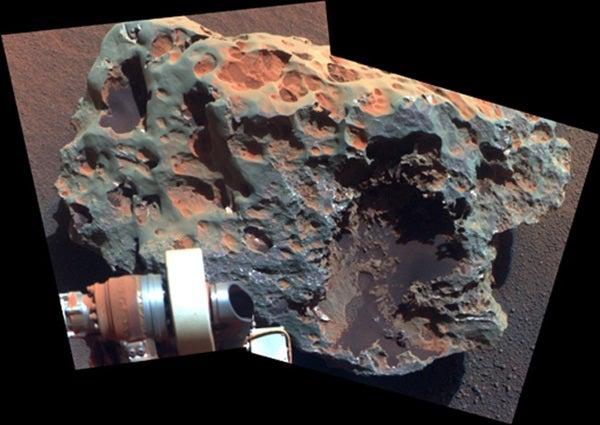

Two weeks ago, Opportunity had driven approximately 600 feet (183 meters) past the rock in a Mars region called Meridiani Planum. An image the rover had taken a few days earlier and stored was then transmitted back to Earth. The image showed the rock is approximately 2 feet (0.6 meters) in length, half that in height, and has a bluish tint that distinguishes it from other rocks in the area. The rover team decided to have Opportunity backtrack for a closer look, eventually touching Block Island with its robotic arm.

“There’s no question that it is an iron-nickel meteorite,” said Ralf Gellert of the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. Gellert is the lead scientist for the rover’s alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, an instrument on the arm used for identifying key elements in an object. “We already investigated several spots that showed elemental variations on the surface. This might tell us if and how the metal was altered since it landed on Mars.”

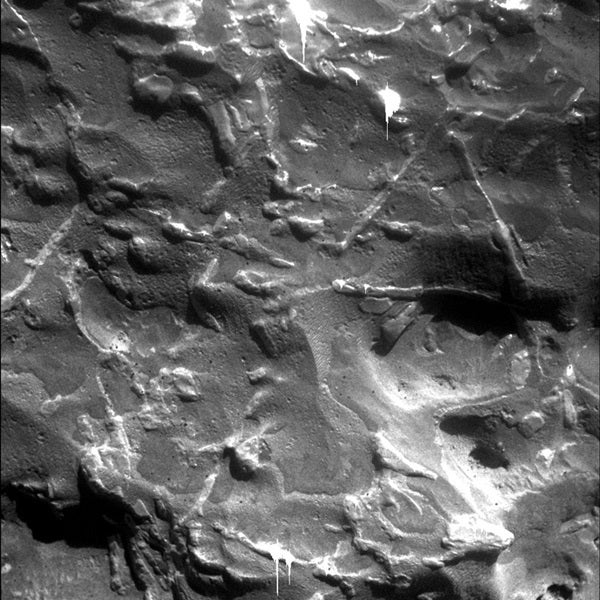

The microscopic imager on the arm revealed a distinctive triangular pattern in Block Island’s surface texture, matching a pattern common in iron-nickel meteorites found on Earth.

“Normally this pattern is exposed when the meteorite is cut, polished, and etched with acid,” said Tim McCoy, a rover team member from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. “Sometimes it shows up on the surface of meteorites that have been eroded by windblown sand in deserts, and that appears to be what we see with Block Island.”

“Consideration of existing model results indicate a meteorite this size requires a thicker atmosphere,” said rover team member Matt Golombek of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “Either Mars has hidden reserves of carbon-dioxide ice that can supply large amounts of carbon-dioxide gas into the atmosphere during warm periods of more recent climate cycles, or Block Island fell billions of years ago.”

Spectrometer observations have already identified variations in the composition of Block Island at different points on the rock’s surface. The differences could result from interaction of the rock with the martian environment, where the metal becomes more rusted from weathering with longer exposures to water vapor or liquid.

“We have lots of iron-nickel meteorites on Earth. We’re using this meteorite as a way to study Mars,” said Albert Yen, a rover team member at JPL. “Before we drive away from Block Island, we intend to examine more targets on this rock where the images show variations in color and texture. We’re looking to see how extensively the rock surface has been altered, which helps us understand the history of the martian climate since it fell.”

When the investigation of Block Island concludes, the team plans to resume driving Opportunity on a route from Victoria Crater, which the rover explored for two years, toward the much larger Endeavour Crater. Opportunity has covered about one-fifth of the 12-mile route plotted for safe travel to Endeavour since the rover left Victoria nearly a year ago.

Opportunity and its twin rover, Spirit, landed on Mars in January 2004 for missions originally planned to last for three months. Both rovers show signs of aging but are still very able to continue to explore and study Mars.