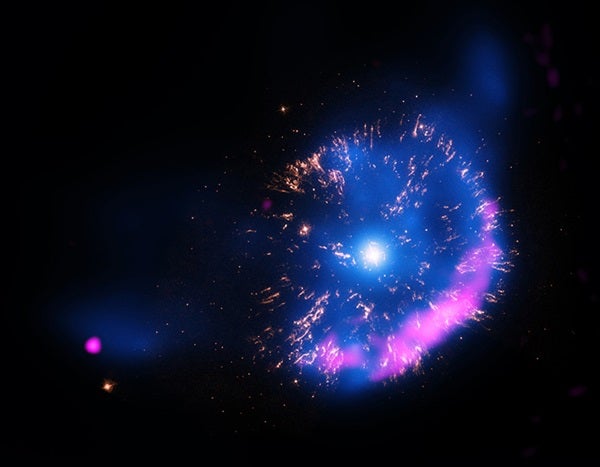

A new image of GK Persei contains X-rays (blue), optical data (yellow), and radio data (pink).

Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers have studied one particular explosion that may provide clues to the dynamics of other, much larger stellar eruptions.

A team of researchers pointed the telescope at GK Persei, an object that became a sensation in the astronomical world in 1901 when it suddenly appeared as one of the brightest stars in the sky for a few days before gradually fading away in brightness. Today, astronomers cite GK Persei as an example of a “classical nova,” an outburst produced by a thermonuclear explosion on the surface of a white dwarf star, the dense remnant of a Sun-like star.

A nova can occur if the strong gravity of a white dwarf pulls material from its orbiting companion star. If enough material, mostly in the form of hydrogen gas, accumulates on the surface of the white dwarf, nuclear fusion reactions can occur and intensify, culminating into a cosmic-sized hydrogen bomb blast. The outer layers of the white dwarf are blown away, producing a nova outburst that can be observed for a period of months to years as the material expands into space.

Classical novae can be considered to be “miniature” versions of supernova explosions. Supernovae signal the destruction of an entire star and can be so bright that they outshine the whole galaxy where they are found. Supernovae are extremely important for cosmic ecology because they inject huge amounts of energy into the interstellar gas and are responsible for dispersing elements such as iron, calcium, and oxygen into space where they may be incorporated into future generations of stars and planets.

Although the remnants of supernovae are much more massive and energetic than classical novae, some of the fundamental physics is the same. Both involve an explosion and creation of a shock wave that travels at supersonic speeds through the surrounding gas.

The more modest energies and masses associated with classical novae means that the remnants evolve more quickly. This, plus the much higher frequency of their occurrence compared to supernovae, makes classical novae important targets for studying cosmic explosions.

Chandra first observed GK Persei in February 2000 and then again in November 2013. This 13-year baseline provides astronomers with enough time to notice important differences in the X-ray emission and its properties.

This new image of GK Persei contains X-rays from Chandra (blue), optical data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (yellow), and radio data from the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array (pink). The X-ray data show hot gas, and the radio data show emission from electrons that have been accelerated to high energies by the nova shock wave. The optical data reveal clumps of material that were ejected in the explosion. The nature of the point-like source on the lower left is unknown.

Over the years that the Chandra data span, the nova debris expanded at a speed of about 700,000 mph (1.1 million km/h). This translates to the blast wave moving about 90 billion miles (145 billion km) during that period.

One intriguing discovery illustrates how the study of nova remnants can provide important clues about the environment of the explosion. The X-ray luminosity of the GK Persei remnant decreased by about 40 percent over the 13 years between the Chandra observations — the temperature of the gas in the remnant has essentially remained constant at about 1,800,000° Fahrenheit (1,000,000° Celsius). As the shock wave expanded and heated an increasing amount of matter, the temperature behind the wave of energy should have decreased. The observed fading and constant temperature suggests that the wave of energy has swept up a negligible amount of gas in the environment around the star over the past 13 years. This suggests that the wave must currently be expanding into a region of much lower density than before, giving clues to the stellar neighborhood in which GK Persei resides.