To get more insight into those processes, Meg Rosenburg and her colleagues at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California, put together the first comprehensive set of maps revealing the slopes and roughness of the Moon’s surface. These maps are based on detailed data collected by the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Like wrinkles on skin, the roughness of craters and other features on the Moon’s surface can reveal their age. “The key is to look at the roughness at both long and short scales,” said Rosenburg.

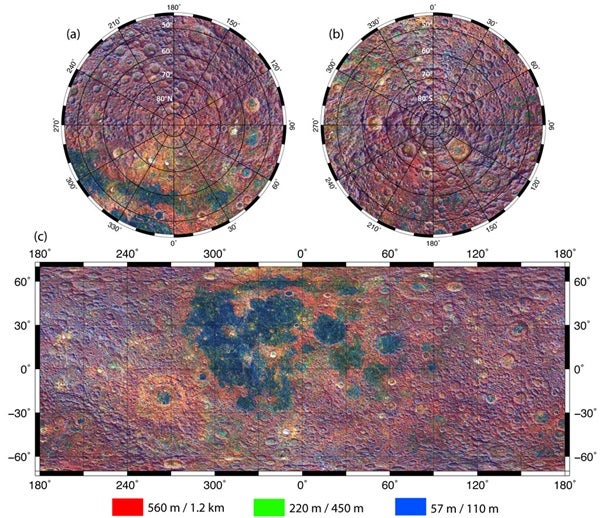

The roughness depends on the subtle ups and downs of the landscape, a quality that the researchers get at by measuring the slope at locations all over the surface. To put together a complete picture, the researchers looked at roughness at a range of different scales — the distances between two points — from 56 feet (17 meters) to as much as 1.6 miles (2.7 kilometers).

“Old and young craters have different roughness properties; they are rougher on some scales and smoother on others,” said Rosenburg. That’s because the older craters have been pummeled for eons by meteorites that pit and mar the site of the original impact, changing the original shape of the crater.

“Because this softening of the terrain hasn’t happened at the new impact sites, the youngest craters immediately stand out,” said Gregory Neumann from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“It is remarkable that the Moon exhibits a great range of topographic character: On the extremes, surfaces roughened by the accumulation of craters over billions of years can be near regions smoothed and resurfaced by more recent mare volcanism,” said Oded Aharonson from Caltech.

By looking at where and how the roughness changes, the researchers can get important clues about the processes that shaped the Moon. A roughness map of the material surrounding Orientale basin, for example, reveals subtle differences in the ejecta, or debris, that was thrown out when the crater was formed by a giant object slamming into the Moon.

That information can be combined with a contour map that shows where the high and low points are. “By looking at both together, we can say that one part of Orientale is not just higher or lower, it’s also differently rough,” Rosenburg said. “That gives us some clues about the impact process that launched the ejecta and also about the surface processes that later acted to modify it.”

Likewise, the smooth plains of maria, which were created by volcanic activity, have a different roughness “signature” from the Moon’s highlands, reflecting the vastly different origins of the two terrains.

Just as on the Moon, the same approach can be used to study surface processes on other bodies as well, Rosenburg says. “The processes at work are different on Mars than they are on an asteroid, but they each leave a signature in the topography for us to interpret. By studying roughness at different scales, we can begin to understand how our nearest neighbors came to look the way they do.”

To get more insight into those processes, Meg Rosenburg and her colleagues at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California, put together the first comprehensive set of maps revealing the slopes and roughness of the Moon’s surface. These maps are based on detailed data collected by the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Like wrinkles on skin, the roughness of craters and other features on the Moon’s surface can reveal their age. “The key is to look at the roughness at both long and short scales,” said Rosenburg.

The roughness depends on the subtle ups and downs of the landscape, a quality that the researchers get at by measuring the slope at locations all over the surface. To put together a complete picture, the researchers looked at roughness at a range of different scales — the distances between two points — from 56 feet (17 meters) to as much as 1.6 miles (2.7 kilometers).

“Old and young craters have different roughness properties; they are rougher on some scales and smoother on others,” said Rosenburg. That’s because the older craters have been pummeled for eons by meteorites that pit and mar the site of the original impact, changing the original shape of the crater.

“Because this softening of the terrain hasn’t happened at the new impact sites, the youngest craters immediately stand out,” said Gregory Neumann from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“It is remarkable that the Moon exhibits a great range of topographic character: On the extremes, surfaces roughened by the accumulation of craters over billions of years can be near regions smoothed and resurfaced by more recent mare volcanism,” said Oded Aharonson from Caltech.

By looking at where and how the roughness changes, the researchers can get important clues about the processes that shaped the Moon. A roughness map of the material surrounding Orientale basin, for example, reveals subtle differences in the ejecta, or debris, that was thrown out when the crater was formed by a giant object slamming into the Moon.

That information can be combined with a contour map that shows where the high and low points are. “By looking at both together, we can say that one part of Orientale is not just higher or lower, it’s also differently rough,” Rosenburg said. “That gives us some clues about the impact process that launched the ejecta and also about the surface processes that later acted to modify it.”

Likewise, the smooth plains of maria, which were created by volcanic activity, have a different roughness “signature” from the Moon’s highlands, reflecting the vastly different origins of the two terrains.

Just as on the Moon, the same approach can be used to study surface processes on other bodies as well, Rosenburg says. “The processes at work are different on Mars than they are on an asteroid, but they each leave a signature in the topography for us to interpret. By studying roughness at different scales, we can begin to understand how our nearest neighbors came to look the way they do.”