Stars in mid- and later life don’t always end up with as many planets as they started with. Early in their evolutionary histories, planetary systems are places of chaos, and some planets get flung out of their star’s grasp entirely, only to end up a rogue world traveling through space.

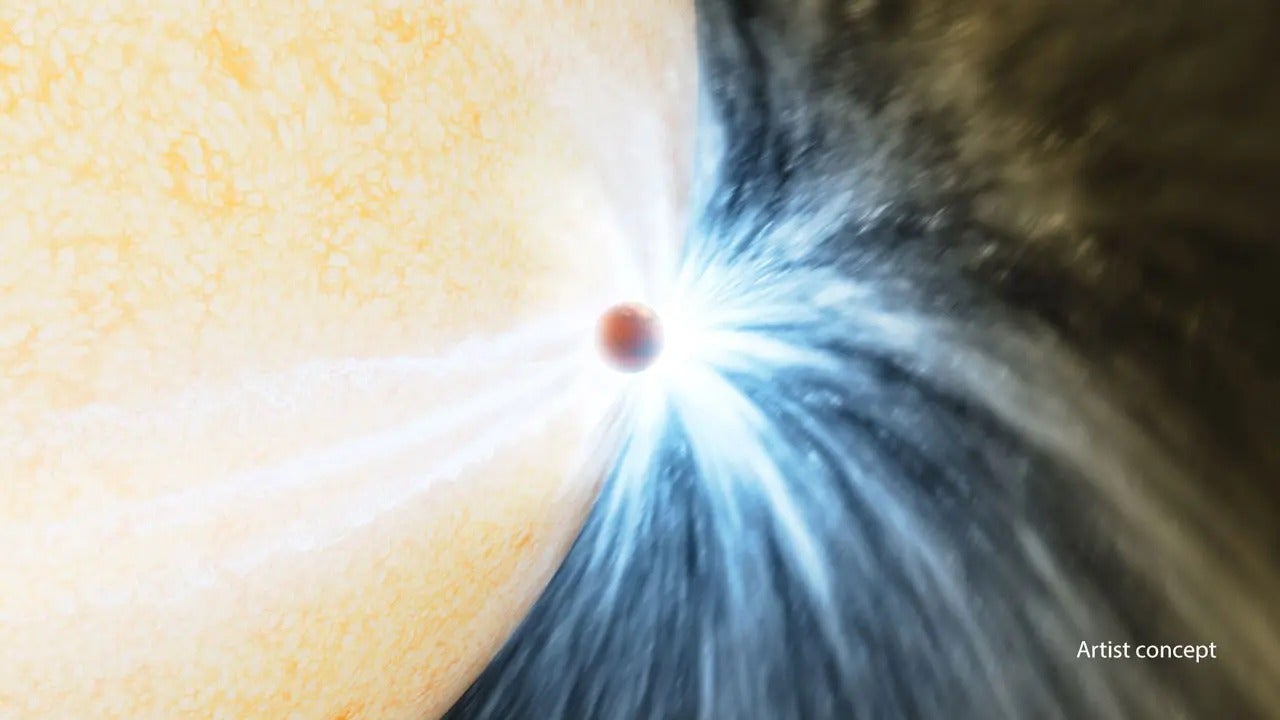

But sometimes planets encounter another risk. A star can lose a planet not due to ejection but due to ingestion. A study published March 20 in Nature surveyed 91 nearby star systems. By looking for small changes in composition, the astronomers behind the study reported that about 1 in 12 had the telltale signatures of having eaten a planet.

Most stars form in pairs. Even our Sun may have had a twin that moved away by gravitational forces. The team behind the new paper, led by Fan Liu of Monash University in Australia, wanted to find evidence of stars that had consumed a planet, but it’s hard to just look at a star and tell if some of its atmosphere has been contaminated by planetary matter. This is because the elements we can observe in a star’s spectrum, in many cases, may simply reflect how the star formed.

That’s why Liu and colleagues looked for pairs with relatively “close” separations, about 1 million times the distance between Earth and the Sun. Although such stars may not orbit each other, that distance suggests the stars likely formed in the same region at the same time, a formation termed as “co-natal” suns.

Co-natal stars, because they share an origin story, should contain roughly the same compositions. Astronomers can examine the chemical composition of a star by breaking down its light, with various lines in its spectrum corresponding to specific elements.

A clue in the composition

Of the 91 pairs surveyed, at least seven fit the criteria the team looked for in finding a star that has devoured a planet. The ratio of elements between the stars was off, often with one containing larger abundances of heavier elements. Liu says that many of these stars were richer in iron, nickel, silicon and aluminum than their companions, suggesting that a planet had been ingested at some point.

“Based on this study and some planet formation/evolution models, it is possible that the planetary ingestion event happened at a few hundred million years [after formation],” he says.

Liu also says that they didn’t find any one thing that united pairs of stars with evidence of feasting events against those that showed no evidence. Examinations of radial velocity data (which can help tell what’s gravitationally influencing a star by looking for small shifts in its spectrum) and magnetic activity could provide some clues.

“If we witness the evidence of planetary ingestion, it may indicate that there are outer perturbers in that stellar-planetary system,” Liu says. “That’s why we are trying to do radial velocity follow-up of our candidates.”

Liu says that while the Sun has some chemical peculiarities, it doesn’t show evidence of any kind of ingestion events.

Future studies could uncover more about these events, a little too reminiscent of a certain famous Goya painting. It could also help astronomers find signs of planetary matter falling into a star. This represents an exciting and relatively new way to investigate the ancient histories of nearby stars.