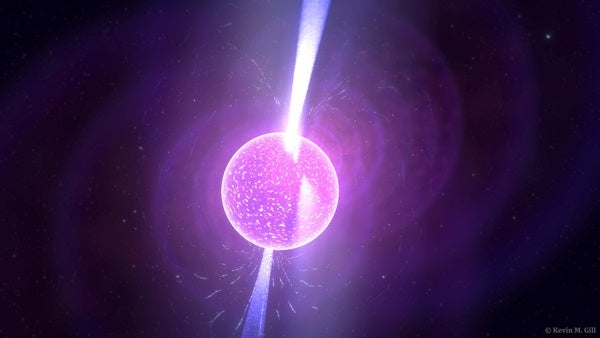

A window in St. Michael’s Church, Much Hoole, England, commemorates Jeremiah Horrocks and his achievement.

Dan Falk

A sample of the “transit of Venus” merchandise for sale in the church in Much Hoole — in this case, a tea towel.

Dan Falk

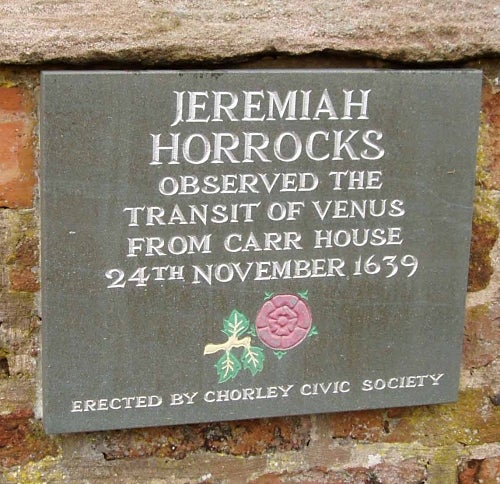

A plaque at Carr House recognizes the building’s importance in the history of astronomy.

Dan Falk

This may be the spot from which Jeremiah Horrocks observed the transit of 1639. A modern replica telescope now looks out of the south-facing bay window on the second floor of Carr House.

Dan Falk

June 7, 2004

Much Hoole, in Lancashire, England, is barely a dot on the map, nestled about 20 miles north of Liverpool. The village of Little Hoole is just up the road — but that’s even less of a dot. To the locals, at any rate, it’s all just “Hoole.”

“Very few people have heard of Hoole,” concedes Eric Barker, a retired government worker and a member of the local church council, as we sit for lunch and a couple drinks at the local pub. “It has very few claims to fame.” When I suggest that Hoole isn’t a household name outside of Lancashire, he laughs. “It’s not even a household name in some parts of Lancashire!”

But the town does have a hero: a brilliant young astronomer named Jeremiah Horrocks, the first person known to have observed a transit of Venus, in 1639. With the first transit of the 21st century just a day away, Horrocks — and the town — are in the limelight.

“The transit is not only a big event in the life of the parish of Hoole church, it’s a big social event as well,” Barker says. Everyone here seems to be looking forward to the June 8 event, and all agree that the transit is the biggest thing to happen to Hoole since — well, in all likelihood, since the last transit in 1882.

Besides public lectures and the viewing of the transit itself, there will be an enormous flower show in St. Michael’s Church that day, with “bacon butties” and other snacks served to one and all. Visitors also will be encouraged to buy transit of Venus tea towels, bookmarks, and paperweights.

“I think the big thing about an event of this size is that it pulls so many people together,” says Barker. “People of different religions, different beliefs. It’s tremendous for the village, for the parish, and for the general community.”

In St. Michael’s Church, Jeremiah Horrocks is revered nearly to the level of sainthood. A stained glass window on the east wall commemorates Horrocks and his achievement. Another window has a famous passage from Psalm 19: “The heavens declare the glory of God.” In the garden outside, a floral arrangement depicts the Sun, Venus, and Earth.

Just a few hundred yards to the south is an old, elegant brick manor called Carr House. The 400-year-old house used to belong to the Stones, a wealthy local family. Horrocks may have been employed here as a tutor for the children. And it was here, in a room on the second floor, that he observed the transit of Venus on a cold winter afternoon nearly 400 years ago. (The house is a private residence, but I was lucky enough to get a quick look inside. It is not generally open to the public.)

Sadly, Horrocks died two years after the transit, at the age of just 22. But even that brief span was enough to secure a place for him — and his charming English town — in the annals of astronomical history.