Numerous studies since 2002 had failed to determine a plausible model for the masses and orbits of two giant planets located closer to 55 Cancri than Mercury is to our Sun. Astronomers had struggled to understand how these massive planets orbiting so close to their star could avoid a catastrophe such as one planet being flung into the star or the two planets colliding with each other. Now, the new study led by Penn State has combined thousands of observations with new statistical and computational techniques to measure the planets’ properties more accurately, revealing that their particular masses and orbits are preventing the system from self-destructing anytime soon.

“The 55 Cancri planetary system is unique in the richness of both the diversity of its known planets and the number and variety of astronomical observations,” said Eric Ford from Penn State. “The complexity of this system makes it unusually challenging to interpret these observations.”

In order to perform the new analyses, Nelson and Ford collaborated with computer scientists to develop a tool for simulating planetary systems using graphics cards to accelerate the computations. By combining multiple types of observations, the Penn State astronomers determined that one of the planets in the system — 55 Cnc e — has eight times the mass of Earth, twice the distance of Earth’s radius, and the same density as that of Earth. This planet is far too hot to have liquid water because its surface temperature is estimated to be 3800° Fahrenheit (2100° Celsius), so it is not likely to host life.

It was only in 2011, eight years after the discovery of this innermost planet, 55 Cnc e, that astronomers recognized it orbited its host star in less than 18 hours, rather than nearly three days, as originally thought. Soon after, astronomers detected the shadow of the planet passing over Earth, allowing astronomers to measure the size of the planet relative to the size of the star.

“These two giant planets of 55 Cancri interact so strongly that we can detect changes in their orbits,” said Nelson. “These detections are exciting because they enable us to learn things about the orbits that are normally not observable. However, the rapid interactions between the planets also present a challenge since modeling the system requires time-consuming simulations for each model to determine the trajectories of the planets and therefore their likelihood of survival for billions of years without a catastrophic collision.”

“One must precisely account for the motion of the giant planets in order to accurately measure the properties of the super-Earth-mass planet,” Ford said. “Most previous analyses had ignored the planet-planet interactions. A few earlier studies had modeled these effects but had performed only simplistic statistical analyses due to the huge number of calculations required for a proper analysis.”

“This research achievement is an example of the scientific breakthroughs that come from data-intensive multidisciplinary research supported by the Penn State Institute for CyberScience,” said Padma Raghavan from the Penn State Institute for CyberScience.

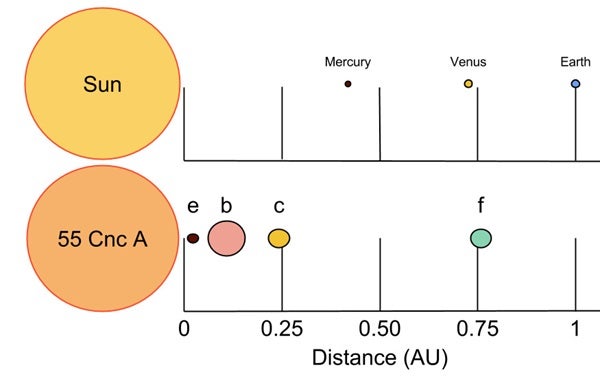

The 55 Cancri planetary system is just 39 light-years away in the constellation Cancer. The system shines brightly when viewed from Earth because it is so close, so astronomers have been able to directly measure the radius of its star — an observation that is practical only for some of our closest stellar neighbors. Knowing the star’s radius made it possible for astronomers to make precise measurements of its mass — nearly the same mass as our Sun — as well as the size and density of its super-Earth-sized planet.

“Because 55 Cancri is so bright that it can be seen with the naked eye, astronomers have been able to measure the velocity of this star from four different observatories over a thousand times, giving the planets in this system much more attention than most exoplanets receive,” said Jason Wright from Penn State.

In 1997, astronomers first discovered that 55 Cancri is orbited by a giant planet. Long-term observations by Wright and colleagues later made possible the detection of five planets orbiting the star, ranging from a cold giant planet with an orbit very similar to that of Jupiter to a scorching-hot “super-Earth” — a type of planet with a mass higher than Earth’s but substantially below that of Neptune, which has a mass 17 times greater than Earth.

Alexander Wolszczan and his colleague Dale Frail from Penn State discovered the first planets ever detected outside our solar system. These planets orbit a distant pulsar star and were the first known super-Earth-mass planets. Recent observations by NASA’s Kepler mission demonstrate that super-Earth-sized planets are common around Sun-like stars.

The study led by Nelson is part of a larger effort to develop techniques that will help with the analysis of future observations in the search for Earth-like planets. Penn State astronomers plan to search for Earth-mass planets around other bright nearby stars, using a combination of new observatories and instruments such as the MINERVA project and the Habitable Zone Planet Finder being built at Penn State for the Hobby-Eberly Telescope. “Astronomers are developing state-of-the-art instrumentation for the world’s largest telescopes to detect and characterize potentially Earth-like planets. We are pairing those efforts with the development of state-of-the-art computational and statistical tools,” Ford said.