During the Cassini spacecraft’s first season of ring studies, the Saturn-circling observatory has yielded remarkable findings, from new structures to a rediscovery of the mercurial spokes the Voyager spacecraft spotted two decades earlier. Cassini imaging team member Joseph Spitale says, “We’re seeing things that were theorized about but never seen. This stuff is right out of a textbook simulation.”

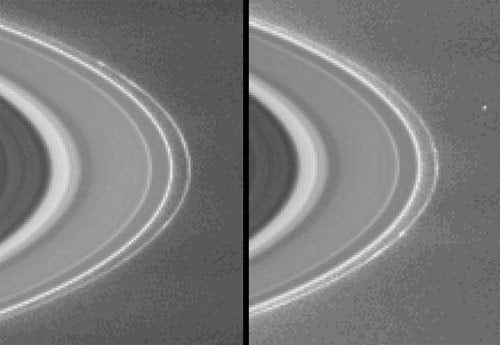

A quarter century ago, the Voyager spacecraft discovered streams of material within Saturn’s rings that traveled around the planet like the spokes of a wheel (see animation at left). But when Cassini arrived at the ringed giant in 2004, the spokes were nowhere to be seen. Finally, Cassini spotted them on the rings’ unilluminated side. The spokes are about 60 miles (100 kilometers) wide and span a radial length of up to 2,200 miles (3,500 km).

In another example of ring activity, the tenuous D ring has shifted locations since the Voyager flybys. The ring has migrated inward by roughly 125 miles (200 km). Another dynamic discovery lies in the tenuous G ring, which appears to have at least one ring segment. This arc of material is similar in structure to the ring arcs encircling Neptune.

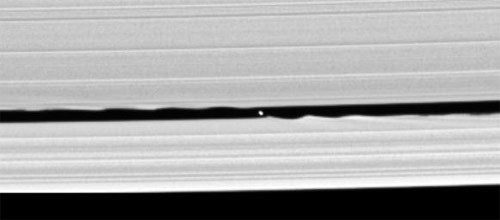

The F ring continues to provide challenges for ring dynamicists. Cassini’s sharp eye is untangling the ring’s clumped nature, revealing a spiral ring just inside the main ring. This spiral defies explanation, although a hidden moon is the chief suspect. No such moons have been found in the F ring yet; instead, images have captured clumps of debris — perhaps harboring a moon just beyond the resolution of Cassini’s imaging system — that seem to cross the ring. The disruptive object, provisionally dubbed S6, appears to plow through the F ring’s core periodically.

Within these three or four moons may lie the answer to the F ring’s twists and turns. But how does the ring interact with the elusive S6? Does the theorized satellite actually collide with the ring? Spitale and the Cassini team may know soon. “If our predictions are right, it will actually hit the ring in April.”

The imaging team will be watching. But even if the moonlet shows up at its predicted location then, it is far too small to scatter as much material as the observations show. Says Spitale, “Even if it turns out to be S6, we still don’t have the mechanism to explain it.”