UPDATE Oct. 7: The Hera mission lifted off today, Monday, Oct. 7 at 10:52 a.m. EDT. The launch livestream can be viewed below via the European Space Agency’s YouTube stream or on X via SpaceX’s account.

Here’s what to know about the Hera mission.

In 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) successfully slammed into the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos and demonstrated that such impacts can change the trajectory of large space rocks — which could come in handy the next time one is heading toward Earth.

Now, DART is getting a follow-up: As early as Monday, the Hera mission will begin its journey to the same asteroid system in a bid to further upgrade Earth’s planetary-defense capabilities.

The uncrewed Hera spacecraft is the European Space Agency’s (ESA) contribution to the study of the Didymos asteroid system. It is expected to lift off from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on Monday aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

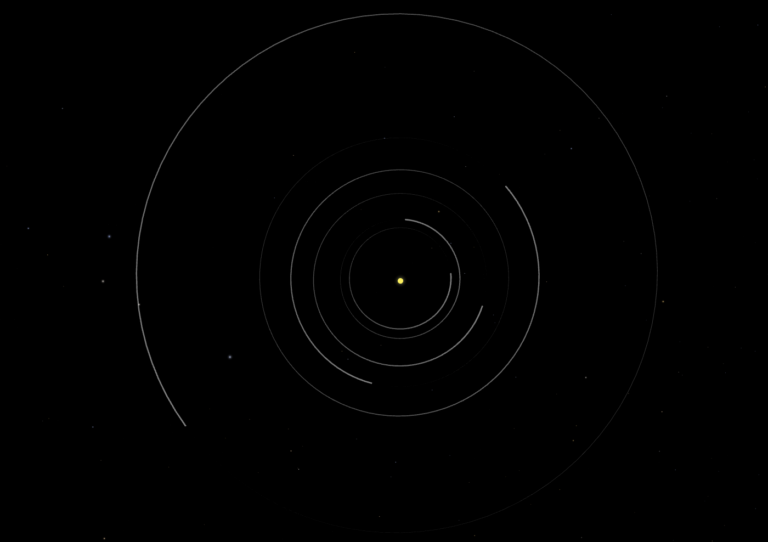

Scheduled to reach the asteroid 65803 Didymos and its moonlet in late 2026, it will gather additional data about the aftermath of the DART crash and how it changed the asteroid system. The mission is key to turning DART’s kinetic impact into a technique that could help save Earth from incoming asteroids in the future.

On Sunday, one potential obstacle to Hera’s launch was removed when the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) approved its SpaceX Falcon 9 for flight. The FAA grounded the Falcon 9 recently because of an incident involving the Crew-9 mission on Sept. 28 in which the rocket’s second stage fell outside of a designated hazard zone in the South Pacific. In a Oct. 6, statement, the FAA said the Falcon 9 was not cleared for all launches, but that Hera’s flight was approved because the second stage would not be reentering the atmosphere; instead, it will boost the craft beyond Earth orbit.

At an Oct. 2 media briefing, project officials said they were still expecting a launch Monday. Hera’s project manager, Ian Carnelli, said during the briefing that between NASA, SpaceX, and the FAA, the Hera team has been kept in the loop on everything. “We are very happy with the progress,” said Carnelli.

An asteroid’s impact

Whether it launches next week or several weeks from now, Hera has a long flight ahead. Equipped with 12 instruments, it will swing by Mars and its moon Deimos in March 2025, where it will use several instruments — its Asteroid Framing Camera, visual and near infrared Hyperscout-H spectrometer, and Thermal Infrared Imager — to examine the objects’ surfaces. This will be an opportunity to test out the equipment before the spacecraft’s final journey to the Didymos system, which orbits just beyond Mars.

Once the car-sized craft nears the Didymos system, the mission’s ground team and the onboard autonomous navigator will assess the state of the debris field surrounding the asteroids. It will then perform a series of braking maneuvers that could take a couple of weeks before arriving at a safe distance to begin its detailed survey of Dimorphos.

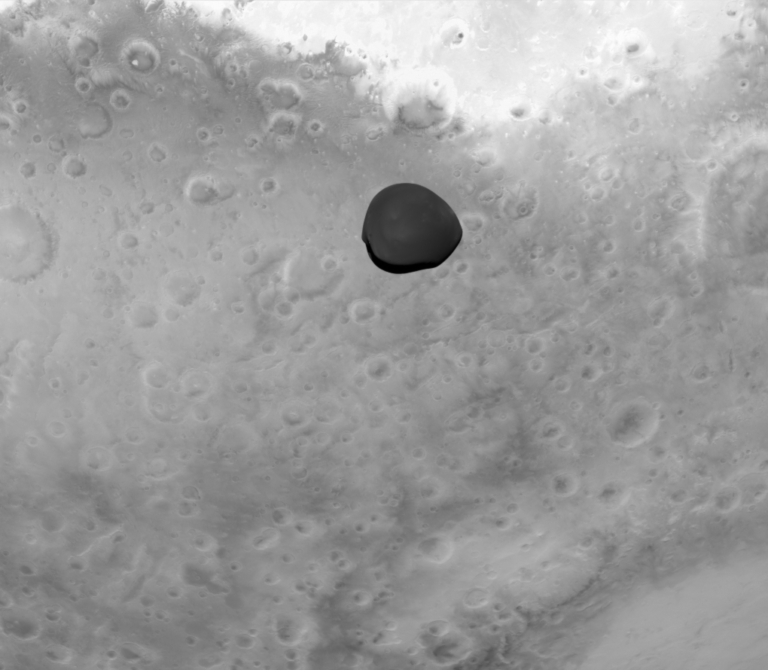

When the DART mission crashed into the moonlet in 2022, it may not have left a crater; some evidence suggests it instead completely reshaped Dimorphos, as well as sent it spinning. Hera is poised to settle this and many other scientific questions from a close-up vantage point. These questions include whether the moonlet is a rubble-pile or a monolith and how much the crash affected Didymos. Hera will first measure the asteroid’s motion from a distance before approaching to within 19 miles (30 kilometers) to better determine its shape.

As it gets closer to the asteroid, Hera will begin mapping it — a project that will continue throughout the mission, including 12 close flybys. It may also eventually land on Dimorphos at the end of its mission.

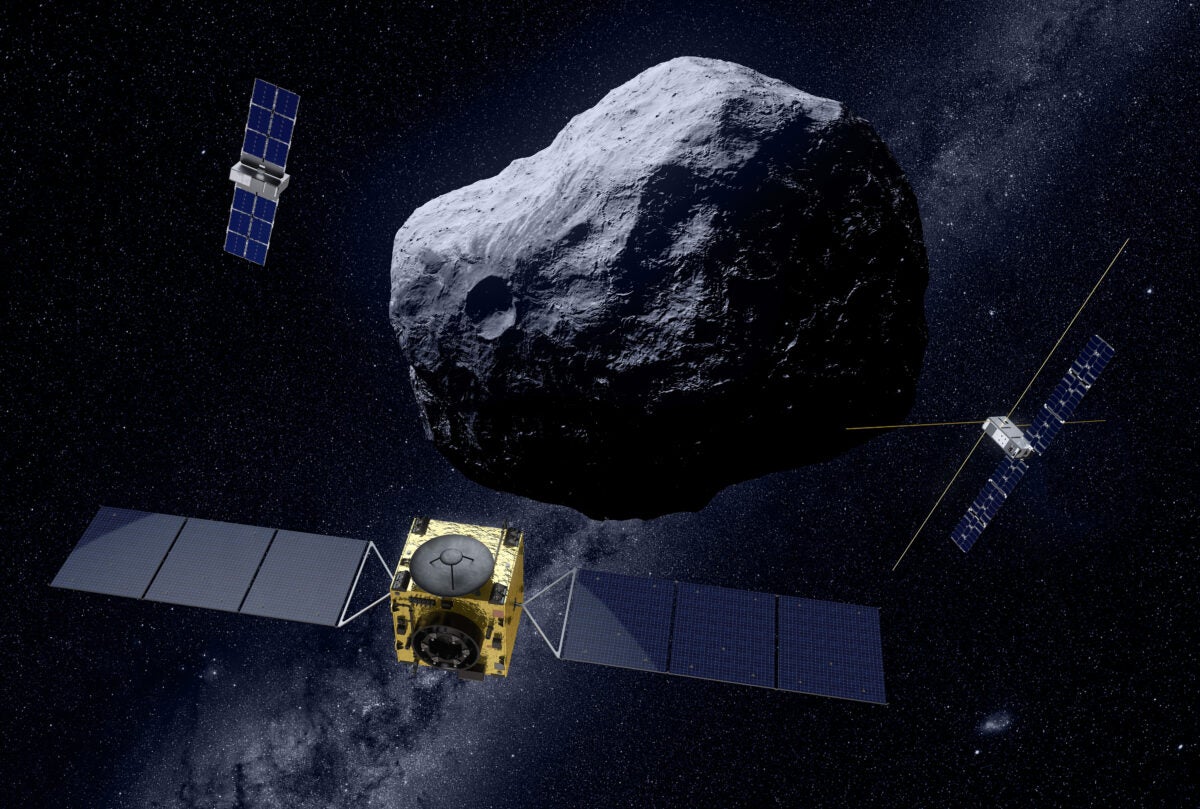

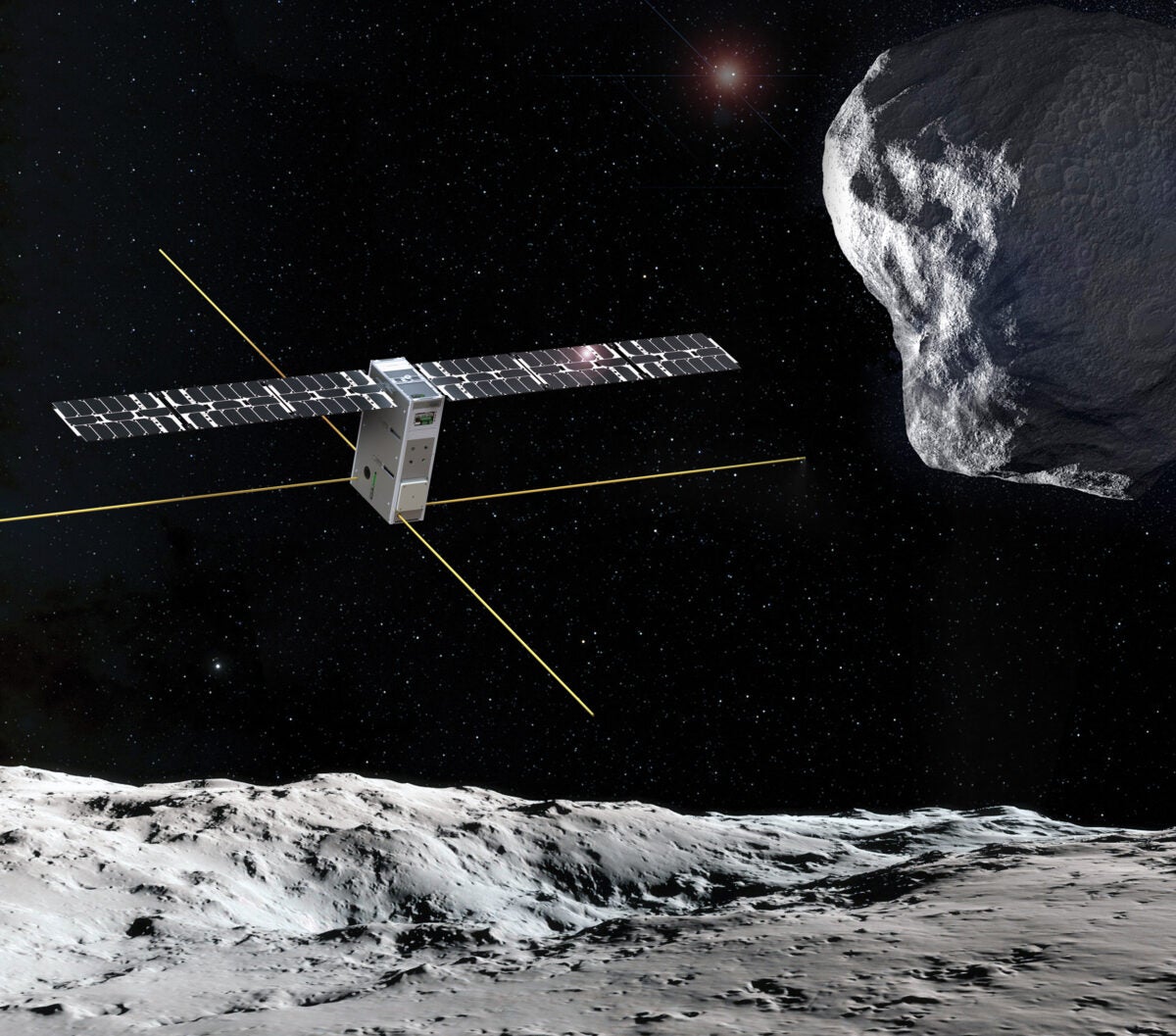

Hera will also deploy two cubesats, each the size of a shoebox, named Juventas and Milani. Each of the cubesats have their own responsibilities and will be led by two separate teams in Italy and Luxembourg.

Juventas, named for the Roman goddess of youth and rejuvenation, will perform radar sounding on Dimorphos with the smallest radar instrument ever flown in space. It will eventually land on the asteroid, which will allow it to precisely measure its gravity.

The other cubesat, Milani, commemorates Andrea Milani, an Italian space scientist who died in 2018. Milani authored the 2005 proposal for a mission concept that would eventually give rise to both DART and Hera. Milani’s purpose is to swoop close to Dimorphos — closer than Hera or Juventas — to measure how much dust surrounds the moonlet and determine its composition with its multispectral imager. Milani will also end its mission by landing on the moonlet.

In the briefing, Canelli said that although Hera’s mission is slated to last six months, there will be enough fuel to last another year. Whether the mission is granted an extension will be determined at a later date.

Ready for launch

Despite the long lead-up to the mission, according to Canelli, it came in under its $400 million (363 million euros) budget. This allowed for the team to begin work on a new upcoming mission called Ramses, which will incorporate many of the same systems as Hera. Ramses will rendezvous with the asteroid 99942 Apophis as shadow it as it makes a close flyby of Earth in 2029.

At the moment, though, the team is focused on getting Hera off the ground. According to ESA, the mission has 20 days to work with, with one instantaneous launch window each day until Oct. 27. Hera also needs to work around another mission launching from KSC, NASA’s Europa Clipper, which has priority. Hera will have to stand down for 48 hours before Europa Clipper’s launch opportunities; the first was scheduled for Oct. 10, but this has been pushed back until Hurricane Milton passes, NASA announced Oct. 6. If Hera does not launch by the end of October, there will not be another opportunity to launch again until October 2026.

“Stakes are high,” said Hera’s flight engineer Ignacio Tanco.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on Oct. 7 with details of Hera’s launch and the postponement of the launch of Europa Clipper.