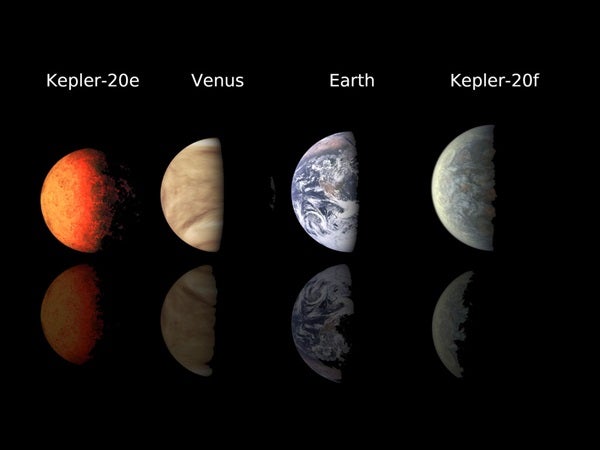

The discovery marks the next important milestone in the ultimate search for planets like Earth. The new planets are thought to be rocky. Kepler-20e is slightly smaller than Venus, measuring 0.87 times the radius of Earth. Kepler-20f is slightly larger than Earth, measuring 1.03 times its radius. Both planets reside in a five-planet system called Kepler-20, approximately 1,000 light-years away in the constellation Lyra.

Kepler-20e orbits its parent star every 6.1 days and Kepler-20f every

19.6 days. These short orbital periods mean very hot, inhospitable worlds. Kepler-20f, at 800° Fahrenheit (427° Celsius), is similar to an average day on the planet Mercury. The surface temperature of Kepler-20e, at more than 1,400° Fahrenheit (760° Celsius), would melt glass.

“The primary goal of the Kepler mission is to find Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone,” said Francois Fressin from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “This discovery demonstrates for the first time that Earth-sized planets exist around other stars, and that we are able to detect them.”

The Kepler-20 system includes three other planets that are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. Kepler-20b, the closest planet, Kepler-20c, the third planet, and Kepler-20d, the fifth planet, orbit their star every 3.7, 10.9, and 77.6 days, respectively. All five planets have orbits lying roughly within Mercury’s orbit in our solar system. The host star belongs to the same G-type class as our Sun, although it is slightly smaller and cooler.

The system has an unexpected arrangement. In our solar system, small, rocky worlds orbit close to the Sun and large, gaseous worlds orbit farther out. In comparison, the planets of Kepler-20 are organized in alternating size: large, small, large, small, and large.

“The Kepler data are showing us some planetary systems have arrangements of planets very different from that seen in our solar system,” said Jack Lissauer from NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “The analysis of Kepler data continues to reveal new insights about the diversity of planets and planetary systems within our galaxy.”

Scientists are not certain how the system evolved, but they do not think the planets formed in their existing locations. They theorize that the planets formed farther from their star and then migrated inward, likely through interactions with the disk of material from which they originated. This allowed the worlds to maintain their regular spacing despite alternating sizes.

The Kepler space telescope detects planets and planet candidates by measuring dips in the brightness of more than 150,000 stars to search for worlds crossing in front of — or transiting — their stars. The Kepler science team requires at least three transits to verify a signal as a planet.

The Kepler team uses ground-based telescopes and the Spitzer Space Telescope to review observations on planet candidates the Kepler spacecraft finds. The star field Kepler observes in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra can be seen only from ground-based observatories in spring through early fall. The data from these other observations help determine which candidates can be validated as planets.

To validate Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, astronomers used a computer program called Blender, which runs simulations to help rule out other astrophysical phenomena masquerading as a planet.

On December 5, the team announced the discovery of Kepler-22b in the habitable zone of its parent star. It is likely to be too large to have a rocky surface. While Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f are Earth-sized, they are too close to their parent star to have liquid water on the surface.

“In the cosmic game of hide and seek, finding planets with just the right size and just the right temperature seems only a matter of time,” said Natalie Batalha from San Jose State University, California. “We are on the edge of our seats knowing that Kepler’s most anticipated discoveries are still to come.”

The discovery marks the next important milestone in the ultimate search for planets like Earth. The new planets are thought to be rocky. Kepler-20e is slightly smaller than Venus, measuring 0.87 times the radius of Earth. Kepler-20f is slightly larger than Earth, measuring 1.03 times its radius. Both planets reside in a five-planet system called Kepler-20, approximately 1,000 light-years away in the constellation Lyra.

Kepler-20e orbits its parent star every 6.1 days and Kepler-20f every

19.6 days. These short orbital periods mean very hot, inhospitable worlds. Kepler-20f, at 800° Fahrenheit (427° Celsius), is similar to an average day on the planet Mercury. The surface temperature of Kepler-20e, at more than 1,400° Fahrenheit (760° Celsius), would melt glass.

“The primary goal of the Kepler mission is to find Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone,” said Francois Fressin from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “This discovery demonstrates for the first time that Earth-sized planets exist around other stars, and that we are able to detect them.”

The Kepler-20 system includes three other planets that are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. Kepler-20b, the closest planet, Kepler-20c, the third planet, and Kepler-20d, the fifth planet, orbit their star every 3.7, 10.9, and 77.6 days, respectively. All five planets have orbits lying roughly within Mercury’s orbit in our solar system. The host star belongs to the same G-type class as our Sun, although it is slightly smaller and cooler.

The system has an unexpected arrangement. In our solar system, small, rocky worlds orbit close to the Sun and large, gaseous worlds orbit farther out. In comparison, the planets of Kepler-20 are organized in alternating size: large, small, large, small, and large.

“The Kepler data are showing us some planetary systems have arrangements of planets very different from that seen in our solar system,” said Jack Lissauer from NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “The analysis of Kepler data continues to reveal new insights about the diversity of planets and planetary systems within our galaxy.”

Scientists are not certain how the system evolved, but they do not think the planets formed in their existing locations. They theorize that the planets formed farther from their star and then migrated inward, likely through interactions with the disk of material from which they originated. This allowed the worlds to maintain their regular spacing despite alternating sizes.

The Kepler space telescope detects planets and planet candidates by measuring dips in the brightness of more than 150,000 stars to search for worlds crossing in front of — or transiting — their stars. The Kepler science team requires at least three transits to verify a signal as a planet.

The Kepler team uses ground-based telescopes and the Spitzer Space Telescope to review observations on planet candidates the Kepler spacecraft finds. The star field Kepler observes in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra can be seen only from ground-based observatories in spring through early fall. The data from these other observations help determine which candidates can be validated as planets.

To validate Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, astronomers used a computer program called Blender, which runs simulations to help rule out other astrophysical phenomena masquerading as a planet.

On December 5, the team announced the discovery of Kepler-22b in the habitable zone of its parent star. It is likely to be too large to have a rocky surface. While Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f are Earth-sized, they are too close to their parent star to have liquid water on the surface.

“In the cosmic game of hide and seek, finding planets with just the right size and just the right temperature seems only a matter of time,” said Natalie Batalha from San Jose State University, California. “We are on the edge of our seats knowing that Kepler’s most anticipated discoveries are still to come.”