Though controversy still surrounds the origin, abundance, and history of water on Mars, this discovery helps resolve the question of where the “missing martian water” may have gone. Scientists continue to study the planet’s historical record, trying to understand the apparent shift from an early wet and warm climate to today’s dry and cool surface conditions.

The reservoir’s existence also may be a key to understanding climate history and the potential for life on Mars.

“There have been hints of a third planetary water reservoir in previous studies of martian meteorites, but our new data require the existence of a water or ice reservoir that also appears to have exchanged with a diverse set of martian samples,” said Tomohiro Usui of the Tokyo Institute of Technology in Japan. “Until this study, there was no direct evidence for this surface reservoir or interaction of it with rocks that have landed on Earth from the surface of Mars.”

Researchers from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., and NASA’s Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division, located at the agency’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, studied three martian meteorites.

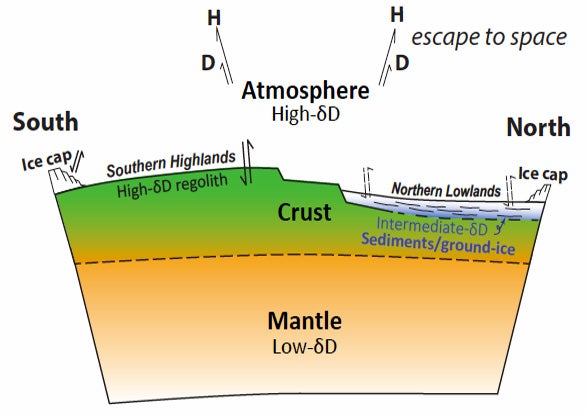

The samples revealed water composed of hydrogen atoms that have a ratio of isotopes distinct from that found in water in the Red Planet’s mantle and current atmosphere. Isotopes are atoms of the same element with differing numbers of neutrons.

While recent orbiter missions have confirmed the presence of subsurface ice and melting ground-ice is believed to have formed some geomorphologic features on Mars, this study used meteorites of different ages to show that significant ground water-ice may have existed relatively intact over time.

Researchers emphasize that the distinct hydrogen isotopic signature of the water reservoir must be of sufficient size that it has not reached isotopic equilibrium with the atmosphere.

“The hydrogen isotopic composition of the current atmosphere could be fixed by a quasi-steady-state process that involves rapid loss of hydrogen to space and the sublimation from a widespread ice layer,” said John Jones, a member of NASA’s Mars Curiosity rover team.

Curiosity’s observations in a lakebed, in an area called Mount Sharp, indicate Mars lost its water in a gradual process over a significant period of time.

“In the absence of returned samples from Mars, this study emphasizes the importance of finding more martian meteorites and continuing to study the ones we have with the ever-improving analytical techniques at our disposal,” said Conel Alexander from the Carnegie Institution for Science.

In this investigation, scientists compared water, other volatile element concentrations and hydrogen isotopic compositions of glasses within the meteorites, which may have formed as the rocks erupted to the surface of Mars in ancient volcanic activity or by impact events that hit the martian surface, knocking them off the planet.

“We examined two possibilities that the signature for the newly identified hydrogen reservoir either reflects near surface ice interbedded with sediment or that it reflects hydrated rock near the top of the martian crust,” said Justin Simon from NASA’s Johnson Space Center. “Both are possible, but the fact that the measurements with higher water concentrations appear uncorrelated with the concentrations of some of the other measured volatile elements, in particular chlorine, suggests the hydrogen reservoir likely existed as ice.”

The information being gathered about Mars from studies on Earth and data being returned from a fleet of robotic spacecraft and rovers on and around the Red Planet are paving the way for future human missions on a journey to Mars in the 2030s.