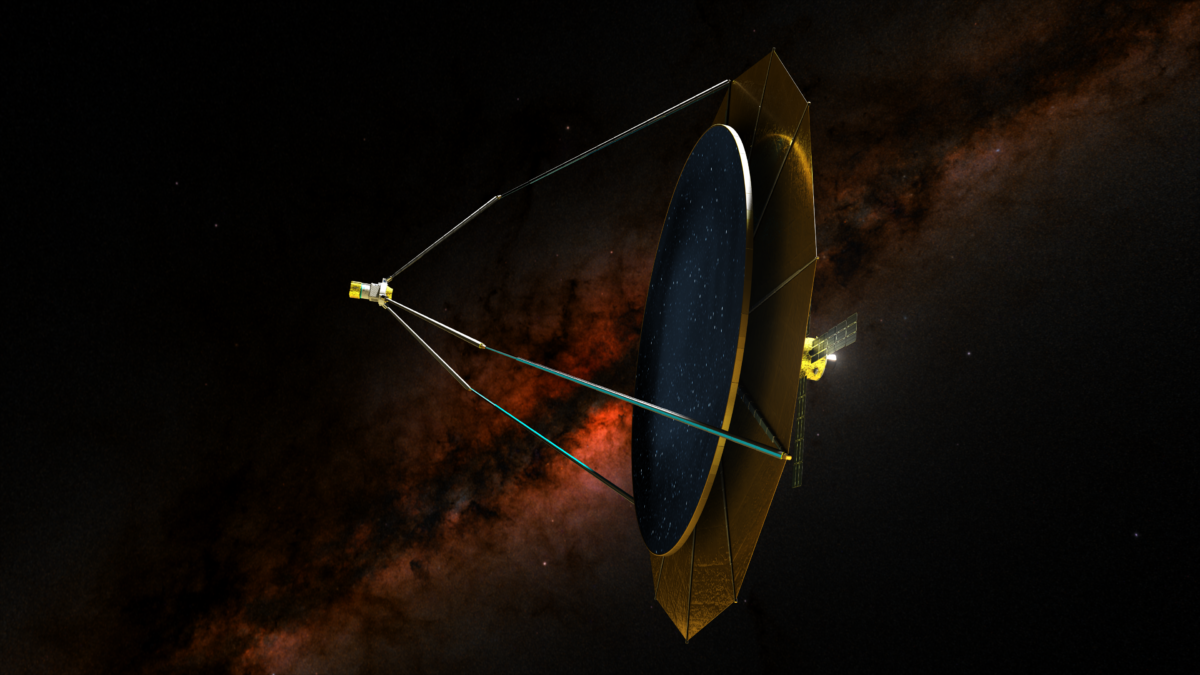

Powerful space telescopes like the 6.5-meter James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will appear like toys compared to future telescopes with liquid mirrors spanning 10 to 100 times that size. Such a dream could indeed become a reality — NASA has now granted the so-called Fluidic Telescope (FLUTE) project three more years of funding to study the technology, the practicalities of the demonstration mission, and a proposed 50-meter space telescope concept.

The idea has already been tested in experiments on low-gravity parabolic flights as well as the International Space Station (ISS), and researchers hope to build an orbital spacecraft to demonstrate a 1-meter liquid-mirror in the next decade or so. Previous studies have also looked at suitable liquids and architectures for such a mirror, as well as monitoring its behavior during spacecraft maneuvers and temperature variations.

The research has been a technological breakthrough that could lead to the creation of ever-larger space telescopes. “Theoretically we can create mirrors as large as we want,” says Ed Balaban, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California who heads the FLUTE project.

Liquids as mirrors

Using liquids to create telescope mirrors is not a new idea; it was suggested by Isaac Newton, who invented a reflecting telescope in 1668.

A few experimental liquid-mirror telescopes have been built here on Earth, but the only one currently operating is the International Liquid Mirror Telescope (ILMT) in northern India, which uses reflections from a spinning 4-meter-wide (13 feet) pool of mercury. The liquid metal forms a concave mirror when it spins. However, the telescope can only look straight up at the zenith, or the mercury would overflow its spinning container.

Earth’s rotation also creates a Coriolis force that would disturb the liquid mirror if it ever became larger than about 26 feet (8 m) across, Balaban tells Astronomy. The solution to this limit, therefore, is to build a liquid-mirror telescope in space.

Solution in space

But there are other challenges as well: Studies by Balaban and his colleagues have found that a liquid mirror wouldn’t form the same stable concave surface in space without constant acceleration, such as gravity or an electromagnetic force. But when that turned out to be unfeasible, the team turned to the results of previous experiments on the ISS, which revealed that in the microgravity of Earth orbit, liquids will form perfect spheres via surface tension. When added into a ringlike frame in the right amount, liquids will then take on a perfect curved shape, such as that needed for a telescopic mirror.

One of the next steps will be determining which liquid to use.

Balaban says the team considered mercury, alloys of gallium, and liquid salts infused with reflective nanoparticles of gold or silver. Unfortunately, both mercury and gallium were found unsuitable. The researchers are now expecting to use a liquid salt that doesn’t freeze or boil in space and has only a superficial layer of reflecting nanoparticles on its surface.

Balaban says a fluidic telescope will work “as long as we have a large enough support frame for the mirror, and enough liquid.”

The future of telescopes

The main obstacles remain the practicalities and costs of producing such a large instrument, and n orbiting fluidic telescope is still at least a decade away, Balaban says.

But once the technology is developed, such a telescope could reveal even more of the hidden universe than JWST, including close-ups of exoplanets, the faintest stars, and the earliest galaxies. For example, a 200-meter-wide fluidic space telescope would have more than 1,000 times the resolution of JWST.

Liquid mirrors can also repair themselves after disturbances like micrometeorite impacts — JWST has reported more than 20 such impacts already.

FLUTE isn’t the only project looking at the feasibility of a liquid mirror. The Ultimately Large Telescope (ULT) proposes to put a 100-meter spinning liquid-mirror scope on the Moon. The Moon’s low gravity means fluid telescopes set up there could be larger than the earthbound analogs.

Telescopes on the Moon also have the advantage of no atmosphere to peer through. And while the ULT would only point at the zenith, like the ILMT, the lack of a complex mount means it could stay useful for more than a decade, says University of Texas at Austin astronomer Volker Bromm, one of ULT’s advocates.

Bromm says that liquid-mirror telescope technology will become vital after the next generation of ground-based extremely large telescopes, or ELTs, are built. These currently include the European Southern Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope and the Giant Magellan Telescope.

“The ELTs will have ‘maxed-out’ conventional solid-mirror technology … [so] the liquid-mirror design paradigm will become front and center,” Bromm says.

Bromm says that a 100-meter ULT could be operating on the Moon by mid-century — about the time that the 50-meter FLUTE concept could go aloft. “FLUTE is … decades away from becoming reality,” Bromm says. “But FLUTE serves as an important pathfinder, to help bridge the gap from the ELTs to the ULT.”