“We have many questions about Europa, the most important and most difficult to answer being, Is there life? Research like this is important because it focuses on questions we can definitively answer, like whether or not Europa is inhabitable,” said Curt Niebur from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Once we have those answers, we can tackle the bigger question about life in the ocean beneath Europa’s ice shell.”

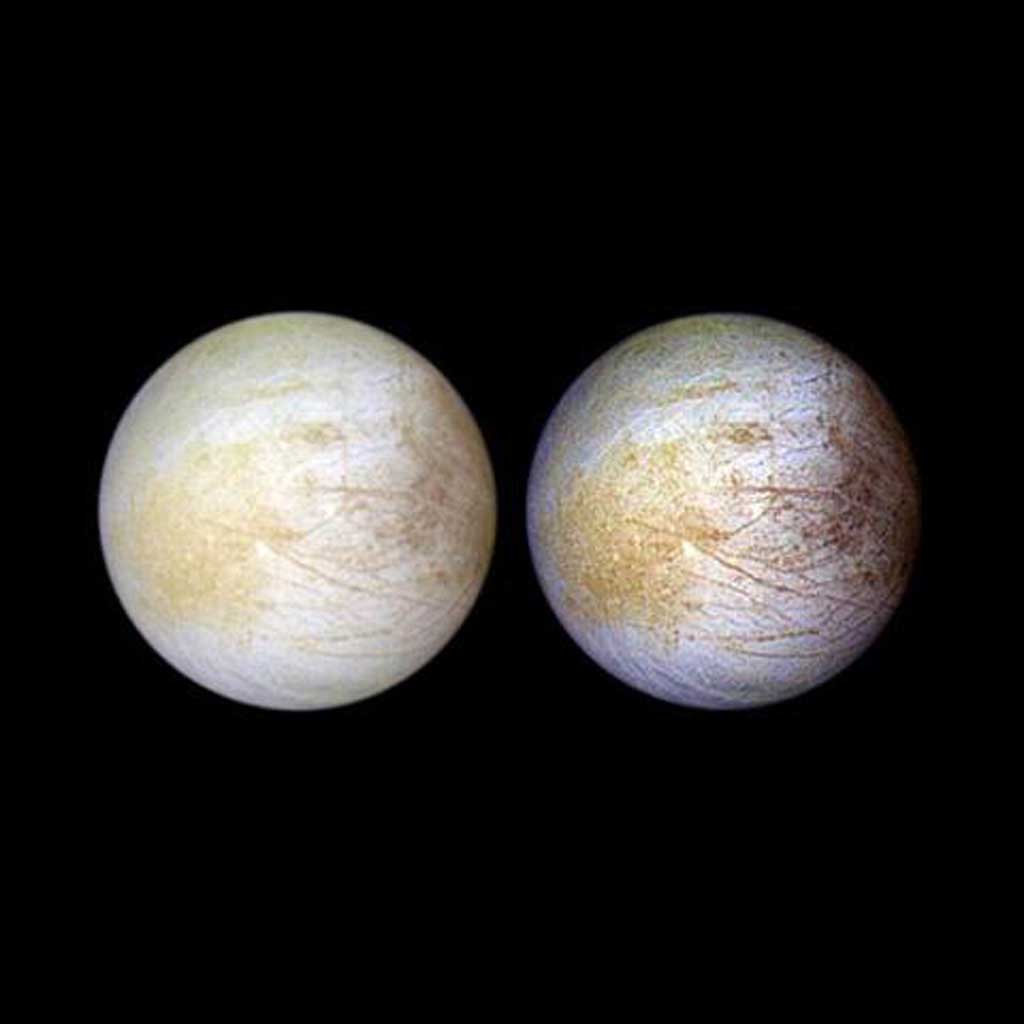

For more than a decade, scientists have wondered about the nature of the dark material that coats long linear fractures and other relatively young geological features on Europa’s surface. Its association with young terrains suggests the material has erupted from within Europa, but with limited data available, the material’s chemical composition has remained elusive.

“If it’s just salt from the ocean below, that would be a simple and elegant solution for what the dark mysterious material is,” said Kevin Hand from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

One certainty is that Europa is bathed in radiation created by Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field. Electrons and ions slam into the moon’s surface with the intensity of a particle accelerator. Theories proposed to explain the nature of the dark material include this radiation as a likely part of the process that creates it.

Previous studies using data from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft and various telescopes attributed the discolorations on Europa’s surface to compounds containing sulfur and magnesium. While radiation-processed sulfur accounts for some of the colors on Europa, the new experiments reveal that irradiated salts could explain the color within the youngest regions of the moon’s surface.

To identify the dark material, Hand and Robert Carlson from JPL created a simulated patch of Europa’s surface in a laboratory test apparatus for testing possible candidate substances. For each material, they collected spectra, which are like chemical fingerprints encoded in the light reflected by the compounds.

“We call it our ‘Europa in a can,'” Hand said. “The lab setup mimics conditions on Europa’s surface in terms of temperature, pressure, and radiation exposure. The spectra of these materials can then be compared to those collected by spacecraft and telescopes.”

For this particular research, the scientists tested samples of common salt — sodium chloride — along with mixtures of salt and water in their vacuum chamber at Europa’s chilly surface temperature of –280° F (–173° C). They then bombarded the salty samples with an electron beam to simulate the intense radiation on the moon’s surface.

After a few tens of hours of exposure to this harsh environment, which corresponds to as long as a century on Europa, the salt samples, which were initially white just like table salt, turned a yellowish-brown color similar to features on the icy moon. The researchers found the color of these samples, as measured in their spectra, showed a strong resemblance to the color within fractures on Europa that were imaged by NASA’s Galileo mission.

“This work tells us the chemical signature of radiation-baked sodium chloride is a compelling match to spacecraft data for Europa’s mystery material,” Hand said.

Additionally, the longer the samples were exposed to radiation, the darker the resulting color. Hand thinks scientists could use this type of color variation to help determine the ages of geologic features and material ejected from any plumes that might exist on Europa.

Previous telescope observations have shown tantalizing hints of the spectral features seen by the researchers in their irradiated salts. But no telescope on or near Earth can observe Europa with sufficiently high resolving power to identify the features with certainty. The researchers suggest this could be accomplished by future observations with a spacecraft visiting Europa.