So, while the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) draws headlines for hunting alien communications like radio waves, most astronomers today are actually looking for the chemical fingerprints of materials tied to life. On Earth, for example, oxygen is our clearest biosignature. It’s the biggest outward change to our planet since the rise of life more than three and a half billion years ago.

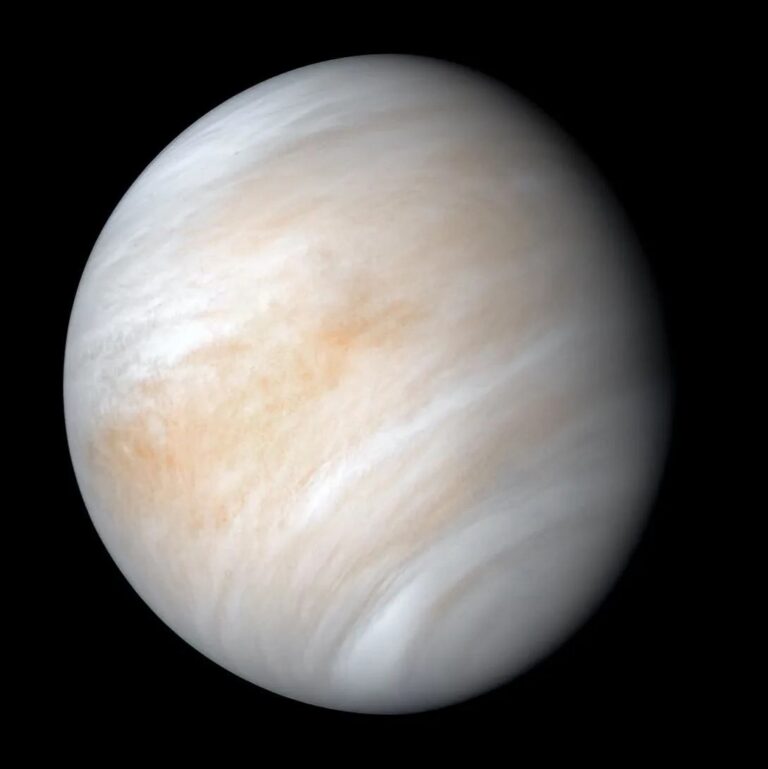

But life isn’t the only way to make oxygen. And astronomers don’t want to be misled if they find an oxygen-rich world.

That’s prompting NASA to launch a project called SISTINE on a sounding rocket that will fly briefly into space next week before falling back to Earth. The idea is to test a new way to observe the stars that exoplanets orbit to better understand how they might scatter false life signs onto their planets.

SISTINE will make its first test launch on August 5, with a second launch planned in 2020.

Looking for life

SISTINE stands for Suborbital Imaging Spectrograph for Transition region Irradiance from Nearby Exoplanet host stars, if you really cheat on how acronyms work. And by sending a rocket just barely into outer space, astronomers can take spectra of nearby stars that host planets. The spectrum of a star tells astronomers exactly what kind of light they give off.

In particular, SISTINE will target ultraviolet light in a range other orbiting telescopes can’t see. This particular color of light can interact with carbon dioxide, splitting away the carbon to leave behind molecular oxygen (two oxygen atoms stuck together). Or, it can strike water vapor, separating hydrogen and oxygen, some of which recombines as molecular oxygen. In these cases, astronomers might be able to spy an atmosphere rich in oxygen, even with no life at all present.

If SISTINE can prove the presence of UV light in the star, it would help astronomers better understand these false positives of ET life.

This particular type of ultraviolet light isn’t common enough from our sun to have a strong effect on Earth’s chemistry, which is why it took life to create large amounts of oxygen in our atmosphere. But that isn’t necessarily the case everywhere.

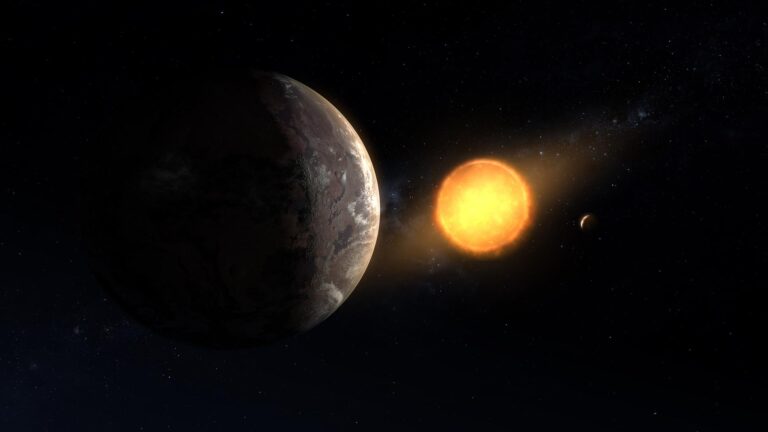

Smaller, dimmer stars called M-dwarfs have a tendency to flare more often than our sun, producing bright streams of ultraviolet light that might well oxygenate their nearby planets.

The first launch of SISTINE will be a mere calibration run, to make sure the telescope can find the right kind of UV light. And instead of an exoplanet, their test targets a cloud of gas called NGC 6826 that’s bright in UV light. If that goes well, they’ll launch again in 2020 to check out the Alpha Centauri system. This is the closest star system to ours, and scientists already know it has exoplanets, too.

The test will also try out new mirror coatings and detector plates and offer new insights into how astronomers can use exoplanets’ host stars to understand false biosignatures. After all, oxygen isn’t the only gas associated with life on Earth; methane is another big one, too. And it can also be mimicked by non-biological processes. By better understanding when and where these substances appear in the absence of life, scientists will be one step closer to knowing the real thing when they see it.