“While we don’t yet know what dark matter is, we do know it interacts with the rest of the universe through gravity, which means it must accumulate around supermassive black holes,” said Jeremy Schnittman from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “A black hole not only naturally concentrates dark matter particles, its gravitational force amplifies the energy and number of collisions that may produce gamma rays.”

In a study, Schnittman describes the results of a computer simulation he developed to follow the orbits of hundreds of millions of dark matter particles, as well as the gamma rays produced when they collide, in the vicinity of a black hole. He found that some gamma rays escaped with energies far exceeding what had been previously regarded as theoretical limits.

In the simulation, dark matter takes the form of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPS) now widely regarded as the leading candidate of what dark matter could be. In this model, WIMPs that crash into other WIMPs mutually annihilate and convert into gamma rays, the most energetic form of light. But these collisions are extremely rare under normal circumstances.

Over the past few years, theorists have turned to black holes as dark matter concentrators where WIMPs can be forced together in a way that increases both the rate and energies of collisions. The concept is a variant of the Penrose process, first identified in 1969 by British astrophysicist Sir Roger Penrose as a mechanism for extracting energy from a spinning black hole. The faster it spins, the greater the potential energy gain.

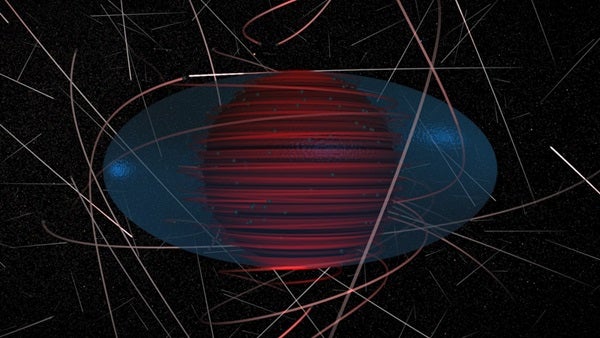

In this process, all of the action takes place outside the black hole’s event horizon, the boundary beyond which nothing can escape, in a flattened region called the ergosphere. Within the ergosphere, the black hole’s rotation drags space-time along with it and everything is forced to move in the same direction at nearly the speed of light. This creates a natural laboratory more extreme than any possible on Earth.

The faster the black hole spins, the larger its ergosphere becomes, which allows high-energy collisions farther from the event horizon. This improves the chances that any gamma rays produced will escape the black hole.

“Previous work indicated that the maximum output energy from the collisional version of the Penrose process was only about 30 percent higher than what you start with,” Schnittman said. In addition, only a small portion of high-energy gamma rays managed to escape the ergosphere. These results suggested that clear evidence of the Penrose process might never be seen from a supermassive black hole.

But the earlier studies included simplifying assumptions about where the highest-energy collisions were most likely to occur. Moving beyond this initial work meant developing a more complete computational model, one that tracked large numbers of particles as they gathered near a spinning black hole and interacted among themselves.

Schnittman’s computer simulation does just that. By tracking the positions and properties of hundreds of millions of randomly distributed particles as they collide and annihilate each other near a black hole, the new model reveals processes that produce gamma rays with much higher energies, as well as a better likelihood of escape and detection, than ever thought possible. He identified previously unrecognized paths where collisions produce gamma rays with a peak energy 14 times higher than that of the original particles.

Using the results of this new calculation, Schnittman created a simulated image of the gamma-ray glow as seen by a distant observer looking along the black hole’s equator. The highest-energy light arises from the center of a crescent-shaped region on the side of the black hole spinning toward us. This is the region where gamma rays have the greatest chance of exiting the ergosphere and being detected by a telescope.

The research is the beginning of a journey Schnittman hopes will one day culminate with the incontrovertible detection of an annihilation signal from dark matter around a supermassive black hole.

“The simulation tells us there is an astrophysically interesting signal we have the potential of detecting in the not too distant future as gamma-ray telescopes improve,” Schnittman said. “The next step is to create a framework where existing and future gamma-ray observations can be used to fine-tune both the particle physics and our models of black holes.”