The first reports of formative gullies on Mars in 2000 generated excitement and headlines because they suggested the presence of liquid water on the Red Planet, the eroding action of which forms gullies here on Earth. Mars has water vapor and plenty of frozen water, but the presence of liquid water on the neighboring planet, a necessity for all known life, has not been confirmed.

“As recently as five years ago, I thought the gullies on Mars indicated activity of liquid water,” said Colin Dundas of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff, Arizona. “We were able to get many more observations, and as we started to see more activity and pin down the timing of gully formation and change, we saw that the activity occurs in winter.”

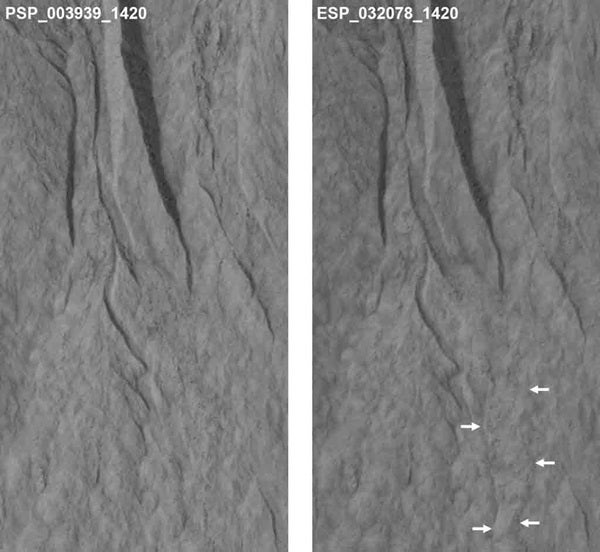

Dundas and collaborators used the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on MRO to examine gullies at 356 sites on Mars beginning in 2006. Thirty-eight of the sites showed active gully formation, such as new channel segments and increased deposits at the downhill end of some gullies.

Using dated before-and-after images, researchers determined the timing of this activity coincided with seasonal carbon-dioxide frost and temperatures that would not have allowed for liquid water.

Frozen carbon dioxide, commonly called dry ice, does not exist naturally on Earth, but it is plentiful on Mars. It has been linked to active processes on Mars such as carbon dioxide gas geysers and lines on sand dunes plowed by blocks of dry ice. One mechanism by which carbon dioxide frost might drive gully flows is by gas that is sublimating from the frost and thus providing lubrication for dry material to flow. Another may be slides due to the accumulating weight of seasonal frost buildup on steep slopes.

The findings in this latest report suggest all of the fresh-appearing gullies seen on Mars can be attributed to processes currently underway, whereas earlier hypotheses suggested they formed thousands to millions of years ago when climate conditions were possibly conducive to liquid water on Mars.

“Much of the information we have about gully formation and other active processes comes from the longevity of MRO and other orbiters,” said Serina Diniega from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “This allows us to make repeated observations of sites to examine surface changes over time.”

Although the findings about gullies point to processes that do not involve liquid water, possible action by liquid water on Mars has been reported in the past year in other findings from the HiRISE team. Those observations were of a smaller type of surface-flow feature.

An upcoming special issue of Icarus will include multiple reports about active processes on Mars, including smaller flows that are strong indications of the presence of liquid water on Mars today.

“I like that Mars can still surprise us,” Dundas said. “Martian gullies are fascinating features that allow us to investigate a process we just don’t see on Earth.”