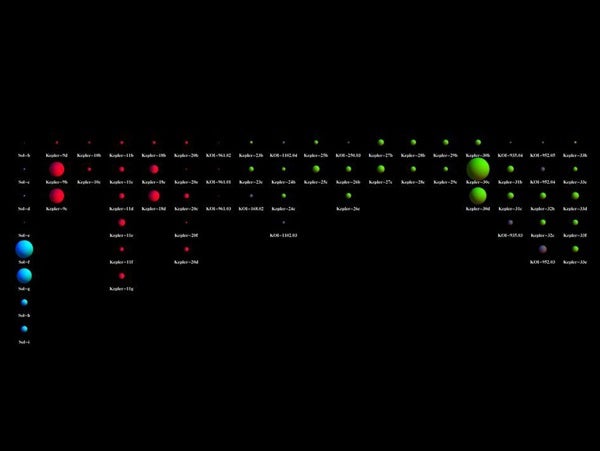

The planets orbit close to their host stars and range in size from 1.5 times the radius of Earth to larger than Jupiter. Fifteen are between Earth and Neptune in size. Further observations will be required to determine which are rocky like Earth and which have thick gaseous atmospheres like Neptune. The planets orbit their host star once every six to 143 days. All are closer to their host star than Venus is to our Sun.

“Prior to the Kepler mission, we knew of perhaps 500 exoplanets across the whole sky,” said Doug Hudgins from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Now, in just two years staring at a patch of sky not much bigger than your fist, Kepler has discovered more than 60 planets and more than 2,300 planet candidates. This tells us that our galaxy is positively loaded with planets of all sizes and orbits.”

Kepler identifies planet candidates by repeatedly measuring the change in brightness of more than 150,000 stars to detect when a planet passes in front of the star. That passage casts a small shadow toward Earth and the Kepler spacecraft.

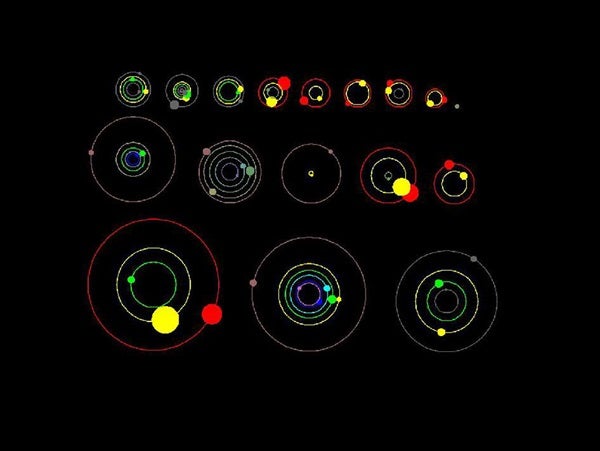

Each of the new confirmed planetary systems contains two to five closely spaced transiting planets. In tightly packed planetary systems, the gravitational pull of the planets on each other causes some planets to accelerate and some to decelerate along their orbits. The acceleration causes the orbital period of each planet to change. Kepler detects this effect by measuring the changes, or Transit Timing Variations (TTVs).

Five of the systems (Kepler-25, Kepler-27, Kepler-30, Kepler-31, and Kepler-33) contain a pair of planets where the inner world orbits the star twice during each orbit of the outer body. Four of the systems (Kepler-23, Kepler-24, Kepler-28, and Kepler-32) contain a pairing where the outer planet circles the star twice for every three times the inner one completes an orbit.

“These configurations help to amplify the gravitational interactions between the planets, similar to how my sons kick their legs on a swing at the right time to go higher,” said Jason Steffen from Fermilab Center for Particle Astrophysics in Batavia, Illinois.

Kepler-33, a star that is older and more massive than our Sun, had the most planets. The system hosts five planets, ranging in size from 1.5 to 5 times that of Earth. All of the planets are located closer to their star than any planet is to our Sun.

The properties of a star provide clues for planet detection. The decrease in the star’s brightness and duration of a planet transit, combined with the properties of its host star, present a recognizable signature. When astronomers detect planet candidates that exhibit similar signatures around the same star, the likelihood of any of these planet candidates being a false positive is very low.

“The approach used to verify the Kepler-33 planets shows the overall reliability is quite high,” said Jack Lissauer from NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. “This is a validation by multiplicity.”