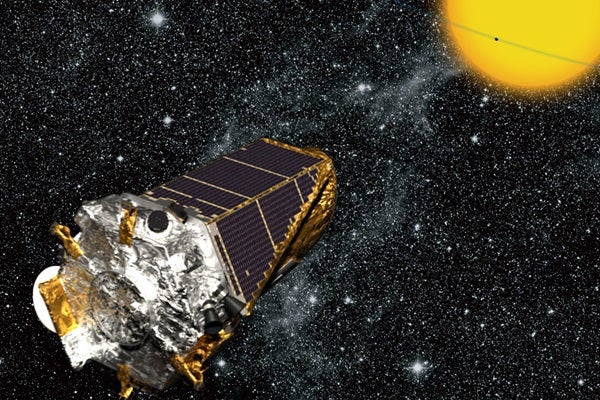

NASA’s Kepler mission successfully launched into space from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta II at 10:49 p.m. EST, Friday, March 6, 2009. Kepler is designed to find the first Earth-sized planets orbiting stars at distances where water could pool on the planet’s surface. Liquid water is believed to be essential for the formation of life.

Bookmark Astronomy.com’s Kepler mission page for ongoing coverage including the latest mission news and editor blogs.

“It was a stunning launch,” said Kepler Project Manager James Fanson of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Our team is thrilled to be a part of something so meaningful to the human race — Kepler will help us understand if our Earth is unique or if others like it are out there.”

Engineers acquired a signal from Kepler at 12:11 a.m. Saturday, March 7, after it separated from its spent third-stage rocket and entered its final Sun-centered orbit, trailing 950 miles (1,530 kilometers) behind Earth. The spacecraft is generating its own power from its solar panels.

“Kepler now has the perfect place to watch more than 100,000 stars for signs of planets,” said William Borucki, the mission’s science principal investigator at NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. “Everyone is very excited as our dream becomes a reality. We are on the verge of learning if other Earths are ubiquitous in the galaxy.”

Engineers have begun to check Kepler to ensure it is working properly — a process called “commissioning” that will take about 60 days. In about a month or less, NASA will send up commands for Kepler to eject its dust cover and make its first measurements. After another month of calibrating Kepler’s single instrument, a wide-field charge-couple device (CCD) camera, the telescope will begin to search for planets.

The first planets to roll out on the Kepler “assembly line” are expected to be the portly “hot Jupiters” — gas giants that circle close and fast around their stars. NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes will be able to follow up with these planets and learn more about their atmospheres. Neptune-sized planets will most likely be found next, followed by rocky ones as small as Earth. The true Earth analogs — Earth-sized planets orbiting stars like our Sun at distances where surface water, and possibly life, could exist — would take at least 3 years to discover and confirm. Ground-based telescopes also will contribute to the mission by verifying some of the finds.

In the end, Kepler will give us our first look at the frequency of Earth-sized planets in our Milky Way Galaxy, as well as the frequency of Earth-sized planets that could theoretically be habitable.

“Even if we find no planets like Earth, that by itself would be profound. It would indicate that we are probably alone in the galaxy,” said Borucki.

As the mission progresses, Kepler will drift farther and farther behind Earth in its orbit around the Sun. NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, which was launched into the same orbit more than 5 years ago, is now more than 62 million miles behind Earth.