Editor’s note: This article was updated Nov. 3 to reflect the discovery that Dinkinesh is actually a binary asteroid pair.

Since its launch two years ago, NASA’s Lucy mission has been traveling the inner solar system on its way to explore Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids. Its first was Nov. 1, and it yielded something special.

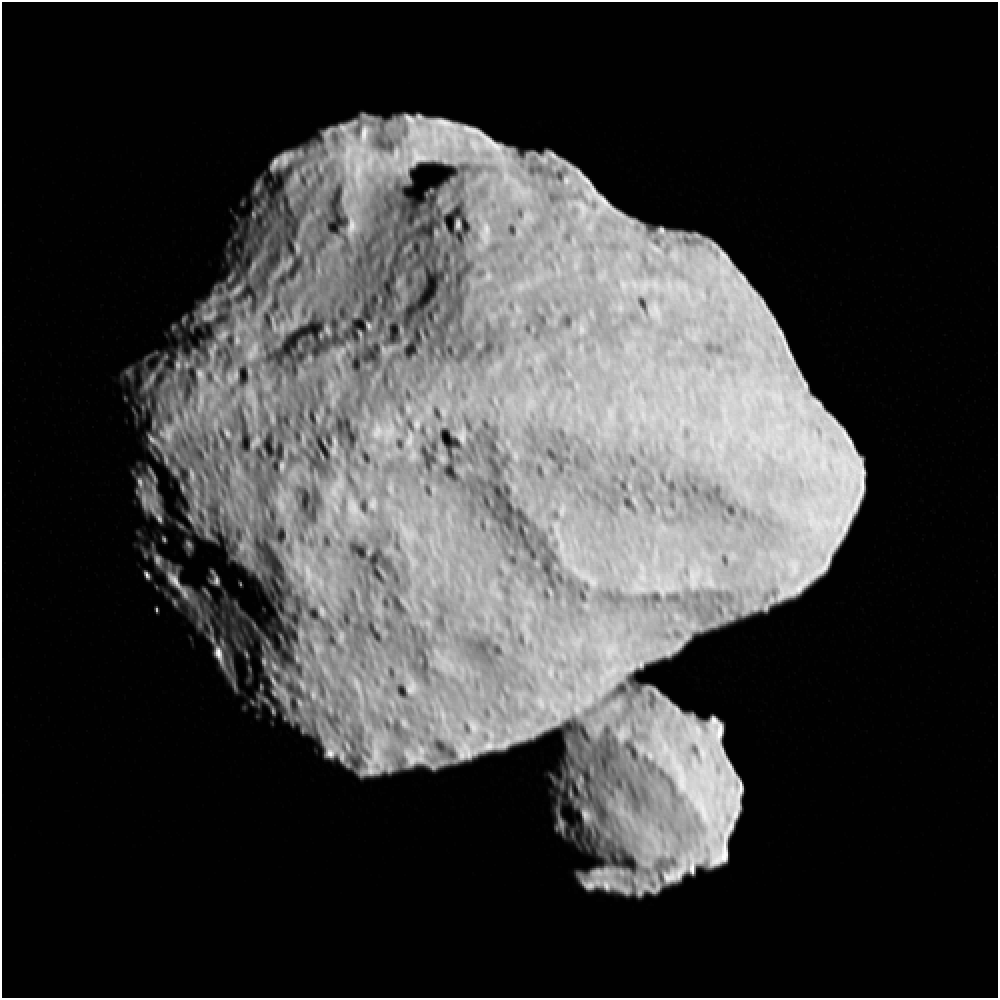

On Wednesday, Lucy zipped past 152830 Dinkinesh, a tiny main-belt asteroid less than half a mile (0.8 kilometer) wide. The flyby, which saw Lucy pass within just 300 miles (480 km) of Dinkinesh, revealed not one, but two asteroids: the larger Dinkinesh and a smaller, 0.15-mile-wide (220 meters) companion. That brings Lucy’s total number of targets now up to 11.

Tracking targets

Lucy is a flyby-only mission, meaning it won’t stop to orbit any of its targets. Instead, it will have to take as much data as possible as it approaches, passes, and pulls away from each asteroid on its list.

But because the asteroids Lucy will visit are so small and far from Earth, it’s difficult for ground-based observations, no matter how meticulous, to exactly pinpoint their position at a specific time. Generally, astronomers’ best guesses for such positions have uncertainties of 100 miles (161 km) or so. While that’s actually quite precise based on the available information, if Lucy had just been sent off with the dates and times researchers thought it should start snapping photos, it could miss its targets entirely!

Instead, the craft has the Terminal Tracking System. This pair of cameras will image its targets as Lucy approaches, providing up-to-the-minute position information that will allow the instruments to autonomously determine when it will be best to collect their valuable data. The information will also ensure the cameras and instruments stay locked on their target during the whole flyby to maximize science output.

And this encounter with Dinkinesh — which is only a recent addition to the mission, more on that shortly — is the perfect chance to test the system, allowing the mission team a low-stakes “dress rehearsal” that will also push the Terminal Tracking System to its limits. That’s because Dinkinesh is much, much smaller than any of Lucy’s other nine targets. This means that rather than a leadup time of hours during which the system will image the asteroid to pinpoint its position, Lucy will only have minutes before the Dinkinesh flyby to accomplish this task.

Chance encounter

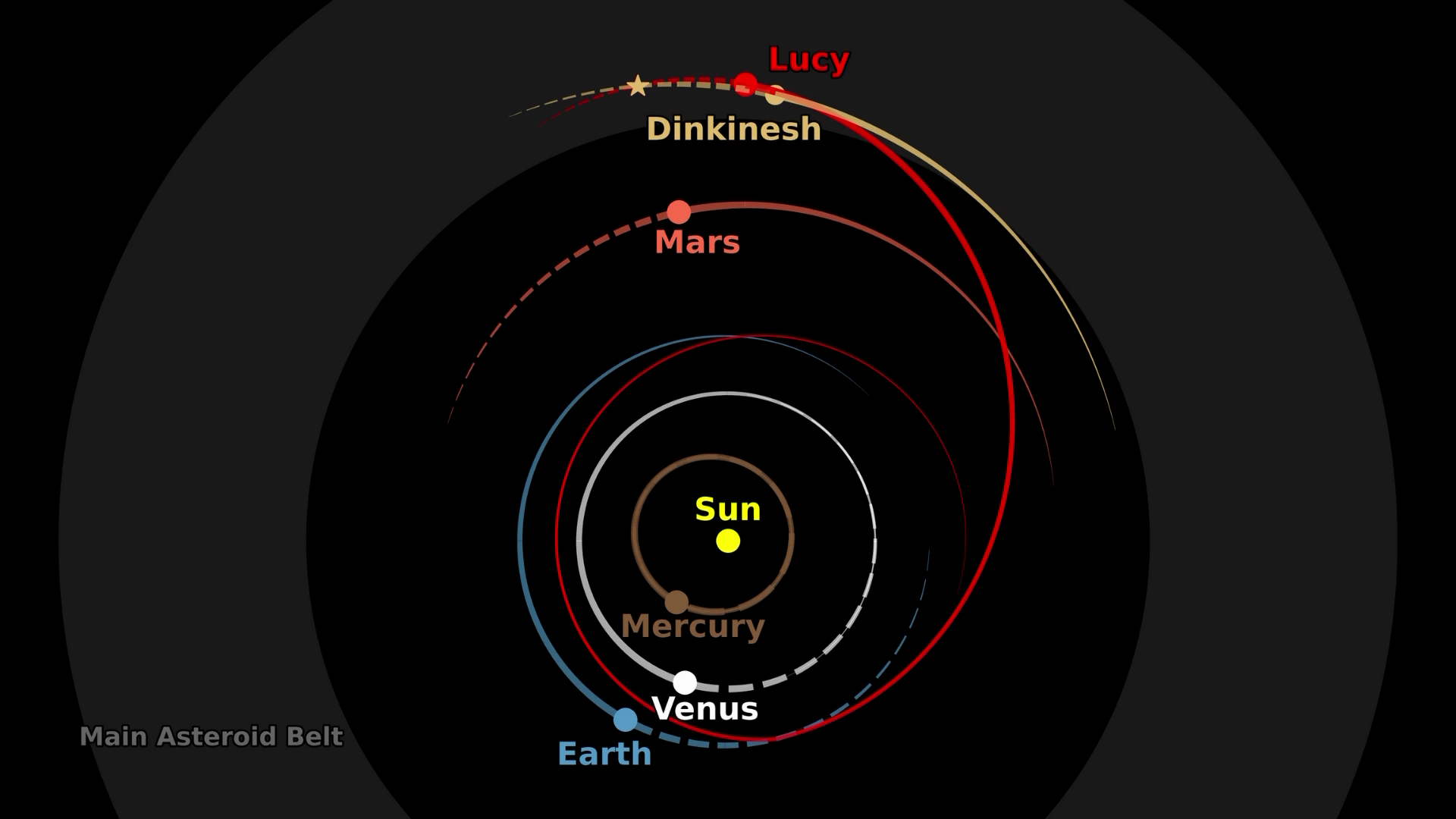

When Lucy launched, the mission only had nine targets: one main-belt asteroid in addition to eight rocky bodies called Trojan asteroids, which occupy orbital sweet spots ahead of or behind Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun.

But like many spacecraft, Lucy isn’t taking a straight route from Earth to Jupiter — to reduce the fuel required, its path is instead a looping one that takes advantage of planetary flybys to give it a gravitational boost. The team knew that in late 2023, Lucy would be skimming the inner edge of the main belt of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter. So, they cross-referenced the spacecraft’s orbit with some half a million known asteroids to look for any that might come close enough for a flyby.

They found one: a tiny world discovered in 1999. Lucy’s original orbit would bring it within 40,000 miles (64,370 km) of the space rock. But the team determined the mission had enough fuel for a course adjustment that would instead allow Lucy to fly within just 300 miles (480 km) of the world.

Earlier this year, following its addition to Lucy’s dance card, the world was officially named Dinkinesh in addition to its standard asteroid number designation. Dinkinesh (ድንቅነሽ) is the Amharic name for the Lucy fossil after which the space mission is named, and means “you are marvelous.”

When Lucy flies past it next week at some 10,000 mph (6,200 km/h), Dinkinesh will become the smallest main-belt world ever imaged up close by a spacecraft. And while any snaps Lucy takes will prove valuable to the engineering team eager to test the tracking, they will also provide vital scientific insight about the world — specifically its shape.

Dinkinesh may be small compared to Lucy’s other targets, but its size is on par with some of the near-Earth asteroids other missions like Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx have visited. So, astronomers are curious about Dinkinesh’s shape because it “may indicate whether near-Earth asteroids — which originate in the main belt — change significantly once they enter near-Earth space,” said Lucy Deputy Principal Investigator Simone Marchi, of Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, in a press release.

“This is really a tiny little asteroid,” said Hal Levison, the mission’s principal investigator, also of SwRI. “Some of the team affectionately refer to it as ‘Dinky.’ But, for a small asteroid, we expect it to be a big help for the Lucy mission.”

Following the Nov. 1 flyby, Lucy will loop back into the inner solar system for an Earth flyby in December next year. Then, Lucy will again test its Terminal Tracking System when it flies past main-belt asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson in April 2025. After that, the craft’s remaining eight targets are the real deal: six Jupiter Trojans, two of which have satellites that will also be studied by the mission.