A little over once a decade, through its New Frontiers program, NASA hosts a battle-royale lottery that sets the tone for the agency’s focus on the future of exploration throughout the solar system. This year, in terms of planetary exploration, NASA decided on sending drones to Titan and a claw-machine to a familiar asteroid.

NASA’s missions are largely split into three camps: the inexpensive missions, a wide assortment of $600- to $700-million missions like the Discovery endeavors, and then there are Flagship missions that set the agency back a cool $2 billion, which launch around every decade or so. The New Frontiers program is somewhere in between; it’s sort of an engineering Hunger Games for space exploration.

NASA accepted twelve mission proposals comprising six themes: comet surface sample return, lunar south pole-Aitken Basin sample return, ocean worlds (e.g., Saturn’s moons Titan and Enceladus), Saturn probe, Trojan asteroid tour and rendezvous and Venus in situ explorer. They whittled these proposals down to two, through an extensive peer review process. These missions will proceed into Phase A development, after which, one will be selected for flight in July 2019, to launch by 2025.

Hail CAESAR

The two missions selected, the Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return (CAESAR) and Dragonfly, would see NASA return to old stomping grounds, but with new technology.

Comets, which are essentially amalgamations of some of the oldest materials in the solar system, are among the most poorly understood, pristine records of the solar system’s history. CAESAR, led by principal investigator Steve Squyres, proposes a return to 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a comet previously explored by the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft.

“By going to that comet, there’s an enormous amount of risk reduction that takes place,” says Squyres. “We’re going to an object we’ve already got good maps of.”

He continued:

“What distinguishes them from every other primitive body out there is what we call their volatile component: ices, the volatile organic compounds that just aren’t present in any other planetary body.”

The CAESAR mission would extract separate volatile and nonvolatile samples from the comet’s icy nucleus, and return them to analysis in November of 2038.

To obtain the volatile samples, which need to stay frozen through a 1,600 degree Celsius reentry, the sample container, provided by the Japanese Space Agency and based off the Hayabusa reentry capsule, can jettison its heat shield once it it’s no longer needed. This way, heat from its outer layer won’t soak through. And powering the entire mission is a solar electric propulsion system, a new technology that NASA has been rolling out in ever-larger iterations—for example, its planned deployment on its planned Asteroid Redirect Robotic Mission–which uses solar power to charge xenon particles, which fly out of an exhaust port, propelling the craft forward.

Fly, Dragonfly

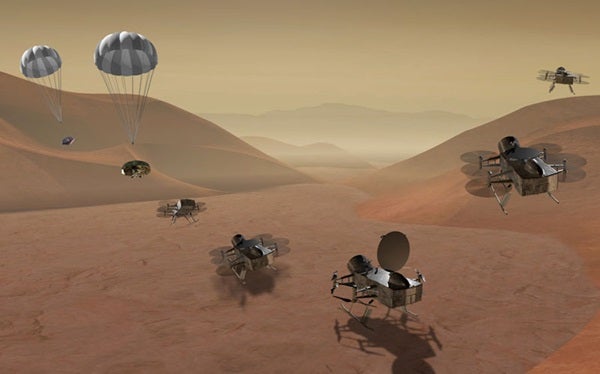

Dragonfly, the second finalist, would set sail to Titan, one of Saturn’s moons.

“Titan is a unique ocean world,” principal investigator Elizabeth Turtle said.

Indeed, Titan is rich with complex hydrocarbons and water beneath its frozen shell, richly detailed by Cassini. The probe itself, a rotocraft, would spend most of its time collecting samples on the ground, studying Titan’s habitability by determining how far prebiotic chemistry has progressed. Turtle said it would be able to fly hundreds of kilometers at a time to make measurements in different geologic settings.

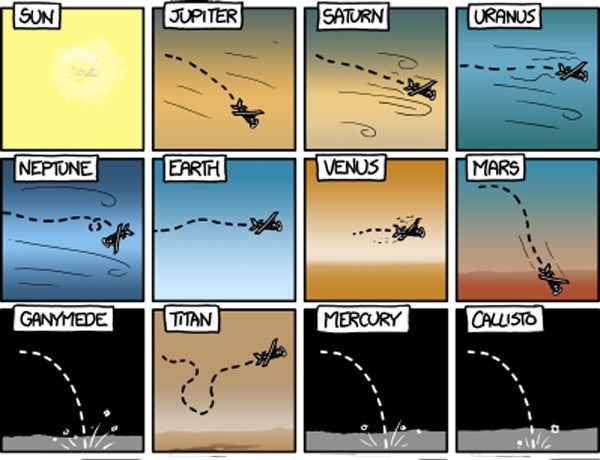

“Indeed, the combination of a dense atmosphere and the low gravity means that it is easier to fly on Titan than on Earth—with wings a person could even fly on Titan!” says Turtle.

In other words, not only could Dragonfly provide groundbreaking science and the satisfying aesthetic of drones on a frozen waterworld…but Randall Munroe, a NASA programmer-cum-XKCD webcomic, may soon be able to fly his Cessna there.

The Best of the Rest

Two other missions, runners-up in a sense, were chosen for further development of specific technologies involved in their mission: The Enceladus Life Signatures and Habitability (ELSAH) and Venus In-situ Composition Investigations (VICI).

The team behind ELSAH, a mission originally aimed to detect life by tracing Cassini’s footsteps through the plumes of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, will continue developing spacecraft sanitation technologies to limit the risk of contamination for future life-detection missions. The team behind VICI, a mission which would’ve sent a probe to the surface of Venus, will continue refining a camera that employed lasers to analyze the elemental composition of rocks in Venus’ perpetual hellscape.

This article originally appeared on Discover.com.