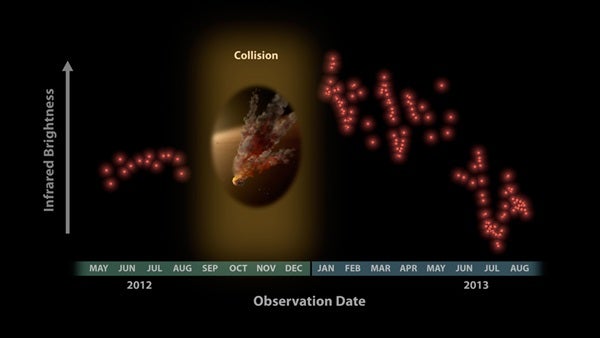

Scientists had been regularly tracking the star, called NGC 2547-ID8, when it surged with a huge amount of fresh dust between August 2012 and January 2013.

“We think two big asteroids crashed into each other, creating a huge cloud of grains the size of very fine sand, which are now smashing themselves into smithereens and slowly leaking away from the star,” said lead author and graduate student Huan Meng of the University of Arizona, Tucson.

While Spitzer has observed dusty aftermaths of suspected asteroid collisions before, this is the first time scientists have collected data before and after a planetary system smashup. The viewing offers a glimpse into the violent process of making rocky planets like ours.

In the new study, Spitzer set its heat-seeking infrared eyes on the dusty star NGC 2547-ID8, which is about 35 million years old and lies 1,200 light-years away in the constellation Vela. Previous observations already had recorded variations in the amount of dust around the star, hinting at possible ongoing asteroid collisions. In hope of witnessing an even larger impact, which is a key step in the birth of a terrestrial planet, the astronomers turned to Spitzer to observe the star regularly. Beginning in May 2012, the telescope began watching the star, sometimes daily.

A dramatic change in the star came during a time when Spitzer had to point away from NGC 2547-ID8 because our Sun was in the way. When Spitzer started observing the star again five months later, the team was shocked by the data they received.

“We not only witnessed what appears to be the wreckage of a huge smashup, but have been able to track how it is changing — the signal is fading as the cloud destroys itself by grinding its grains down so they escape from the star,” said Kate Su of the University of Arizona and co-author on the study. “Spitzer is the best telescope for monitoring stars regularly and precisely for small changes in infrared light over months and even years.”

A very thick cloud of dusty debris now orbits the star in the zone where rocky planets form. As the scientists observe the star system, the infrared signal from this cloud varies based on what is visible from Earth. For example, when the elongated cloud is facing us, more of its surface area is exposed and the signal is greater. When the head or the tail of the cloud is in view, less infrared light is observed. By studying the infrared oscillations, the team is gathering first-of-its-kind data on the detailed process and outcome of collisions that create rocky planets like Earth.

“We are watching rocky planet formation happen right in front of us,” said George Rieke, a University of Arizona co-author of the new study. “This is a unique chance to study this process in near real-time.”

The team is continuing to keep an eye on the star with Spitzer. They will see how long the elevated dust levels persist, which will help them calculate how often such events happen around this and other stars, and they might see another smashup while Spitzer looks on.