But a group of scientists on the mission made a case for changing the plan. They asked that the Relativistic Electron Proton Telescope (REPT) be turned on early — just three days after launch — in order that its observations would overlap with another mission called SAMPEX (Solar, Anomalous, and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer) that was soon going to de-orbit and re-enter Earth’s atmosphere.

It was a lucky decision. Shortly before REPT turned on, solar activity on the Sun had sent energy toward Earth that caused the radiation belts to swell. The REPT instrument worked well from the moment it was turned on September 1. It made observations of these new particles trapped in the belts, recording their high energies, and the belts’ increased size.

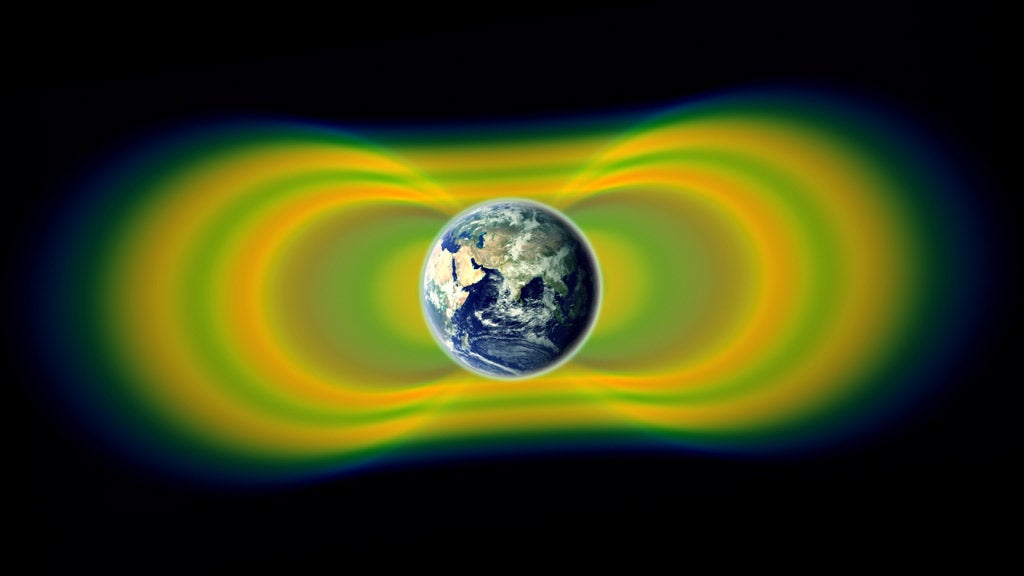

Then something happened no one had ever seen before: The particles settled into a new configuration, showing an extra, third belt extending out into space. Within mere days of launch, the Van Allen Probes showed scientists something that would require rewriting textbooks.

“By the fifth day REPT was on, we could plot out our observations and watch the formation of a third radiation belt,” said Shri Kanekal, the deputy mission scientist for the Van Allen Probes at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland,. “We started wondering if there was something wrong with our instruments. We checked everything, but there was nothing wrong with them. The third belt persisted beautifully, day after day, week after week, for four weeks.”

Incorporating this new configuration into their models of the radiation belts offers scientists new clues to what causes the changing shapes of the belts — a region that can sometimes swell dramatically in response to incoming energy from the Sun, impacting satellites and spacecraft or pose potential threats to manned space flight.

The Van Allen Probes consist of two identical spacecraft with a mission to map out this region with exquisite detail, cataloging a wide range of energies and particles, and tracking the zoo of magnetic waves that pulse through the area, sometimes kicking particles up to such frenzied speeds that they escape the belts altogether.

“We’ve had a long run of data from missions like SAMPEX,” said Daniel Baker, who is the principal investigator for REPT at the University of Colorado in Boulder. “But we’ve never been in the very throat of the accelerator operating a few hundred miles above our head, speeding these particles up to incredible velocities.”

In its first six months in orbit, the instruments on the Van Allen Probes have worked exceptionally well, and scientists are excited about a flood of observations coming in with unprecedented clarity. This is the first time scientists have been able to gather such a complete set of data about the belts, with the added bonus of watching from two separate spacecraft that can better show how events sweep across the area.

Spotting something new in space such as the third radiation belt has more implications than the simple knowledge that a third belt is possible. In a region of space that remains so mysterious, any observations that link certain causes to certain effects adds another piece of information to the puzzle.

Baker likes to compare the radiation belts to the particle storage rings in a particle physics accelerator. In accelerators, magnetic fields are used to hold the particles orbiting in a circle while energy waves are used to buffet the particles up to ever faster speeds. In such accelerators, everything must be carefully tuned to the size and shape of that ring and the characteristics of those particles. The Van Allen belts depend on similar fine-tuning. Given that scientists see the rings only in certain places and at certain times, they can narrow down just which particles and waves must be causing that geometry. Every new set of observations helps narrow the field even further.

“We can offer these new observations to the theorists who model what’s going on in the belts,” said Kanekal. “Nature presents us with this event — it’s there, it’s a fact, you can’t argue with it — and now we have to explain why it’s the case. Why did the third belt persist for four weeks? Why does it change? All of this information teaches us more about space.”

Despite the 55 years since the radiation belts were first discovered, there is much left to investigate and explain, and within just a few days of launch, the Van Allen Probes showed that the belts are still capable of surprises.

“I consider ourselves very fortunate,” said Baker. “By turning on our instruments when we did, taking great pride in our engineers and having confidence that the instruments would work immediately and having the cooperation of the Sun to drive the system the way it did — it was an extraordinary opportunity. It validates the importance of this mission and how important it is to revisit the Van Allen belts with new eyes.”