Scientists study jets to learn more about the extreme environments around black holes. Much has been learned about the material feeding black holes, called accretion disks, and the jets themselves through studies using X-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves. But key measurements of the brightest part of the jets, located at their bases, have been difficult despite decades of work. WISE is offering a new window into this missing link through its infrared observations.

“Imagine what it would be like if our Sun were to undergo sudden random bursts, becoming 3 times brighter in a matter of hours, and then fading back again. That’s the kind of fury we observed in this jet,” said Poshak Gandhi from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). “With WISE’s infrared vision, we were able to zoom in on the inner regions near the base of the stellar-mass black hole’s jet for the first time and the physics of jets in action.”

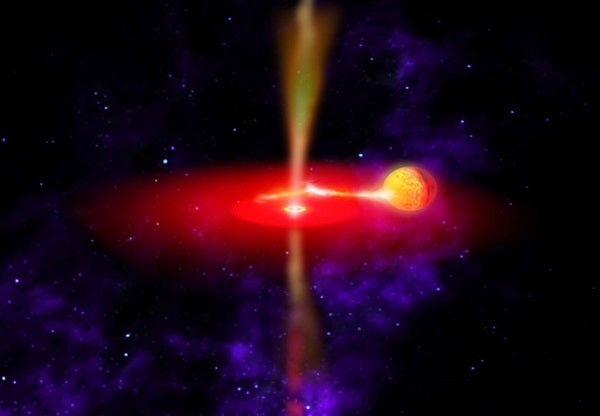

The black hole, called GX 339-4, had been observed previously. It lies more than 20,000 light-years from Earth near the center of our galaxy. It has a mass at least 6 times greater than the Sun. Like other black holes, it is an ultra-dense collection of matter, with gravity is so great that even light cannot escape. In this case, the black hole is orbited by a companion star that feeds it. Most of the material from the companion star is pulled into the black hole, but some of it is blasted away as a jet flowing at nearly the speed of light.

“To see bright flaring activity from a black hole, you need to be looking at the right place at the right time,” said Peter Eisenhardt from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “WISE snapped sensitive infrared pictures every 11 seconds for a year, covering the whole sky, allowing it to catch this rare event.”

Observing the jet’s variability was possible because of images taken of the same patch of sky over time, a feature of NEOWISE, the asteroid-hunting portion of the WISE mission. WISE data enabled the team to zoom in on the compact region around the base of the jet streaming from the black hole. The size of the region is equivalent to the width of a dime seen at the distance of our Sun.

The results surprised the team, showing huge and erratic fluctuations in the jet activity on time scales ranging from 11 seconds to a few hours. The observations are like a dance of infrared colors and show the size of the jet’s base varies. Its radius is approximately 15,000 miles (24,000 kilometers) with dramatic changes by as large a factor of 10 or more.

“If you think of the black hole’s jet as a fire hose, then it’s as if we’ve discovered the flow is intermittent, and the hose itself is varying wildly in size,” Poshak said.

The new data also allowed astronomers to make the best measurements yet of the black hole’s magnetic field, which is 30,000 times more powerful than the one generated by Earth at its surface. Such a strong field is required for accelerating and channeling the flow of matter into a narrow jet. The WISE data is bringing astronomers closer than ever to understanding how this exotic phenomenon works.

Scientists study jets to learn more about the extreme environments around black holes. Much has been learned about the material feeding black holes, called accretion disks, and the jets themselves through studies using X-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves. But key measurements of the brightest part of the jets, located at their bases, have been difficult despite decades of work. WISE is offering a new window into this missing link through its infrared observations.

“Imagine what it would be like if our Sun were to undergo sudden random bursts, becoming 3 times brighter in a matter of hours, and then fading back again. That’s the kind of fury we observed in this jet,” said Poshak Gandhi from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). “With WISE’s infrared vision, we were able to zoom in on the inner regions near the base of the stellar-mass black hole’s jet for the first time and the physics of jets in action.”

The black hole, called GX 339-4, had been observed previously. It lies more than 20,000 light-years from Earth near the center of our galaxy. It has a mass at least 6 times greater than the Sun. Like other black holes, it is an ultra-dense collection of matter, with gravity is so great that even light cannot escape. In this case, the black hole is orbited by a companion star that feeds it. Most of the material from the companion star is pulled into the black hole, but some of it is blasted away as a jet flowing at nearly the speed of light.

“To see bright flaring activity from a black hole, you need to be looking at the right place at the right time,” said Peter Eisenhardt from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “WISE snapped sensitive infrared pictures every 11 seconds for a year, covering the whole sky, allowing it to catch this rare event.”

Observing the jet’s variability was possible because of images taken of the same patch of sky over time, a feature of NEOWISE, the asteroid-hunting portion of the WISE mission. WISE data enabled the team to zoom in on the compact region around the base of the jet streaming from the black hole. The size of the region is equivalent to the width of a dime seen at the distance of our Sun.

The results surprised the team, showing huge and erratic fluctuations in the jet activity on time scales ranging from 11 seconds to a few hours. The observations are like a dance of infrared colors and show the size of the jet’s base varies. Its radius is approximately 15,000 miles (24,000 kilometers) with dramatic changes by as large a factor of 10 or more.

“If you think of the black hole’s jet as a fire hose, then it’s as if we’ve discovered the flow is intermittent, and the hose itself is varying wildly in size,” Poshak said.

The new data also allowed astronomers to make the best measurements yet of the black hole’s magnetic field, which is 30,000 times more powerful than the one generated by Earth at its surface. Such a strong field is required for accelerating and channeling the flow of matter into a narrow jet. The WISE data is bringing astronomers closer than ever to understanding how this exotic phenomenon works.