NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) completed its first survey of the entire sky July 17. The mission has generated more than one million images so far, everything from asteroids to distant galaxies.

“Like a globe-trotting shutterbug, WISE has completed a world tour with 1.3 million slides covering the whole sky,” said Edward Wright from University of California, Los Angeles.

Some of these images have been processed and stitched together into a new picture. It shows the Pleiades cluster of stars, also known as the Seven Sisters, resting in a tangled bed of wispy dust. The pictured region covers 7 square degrees, or an area equivalent to 35 Full Moons, highlighting the telescope’s ability to take wide shots of vast regions of space.

The new picture was taken in February. It shows infrared light from WISE’s four detectors in a range of wavelengths. This infrared view highlights the region’s expansive dust cloud, which the Seven Sisters and other stars in the cluster are passing through. Infrared light also reveals the smaller and cooler stars of the family.

“The WISE all-sky survey is helping us sift through the immense and diverse population of celestial objects,” said Hashima Hasan from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “It’s a great example of the high impact science that’s possible from NASA’s Explorer Program.”

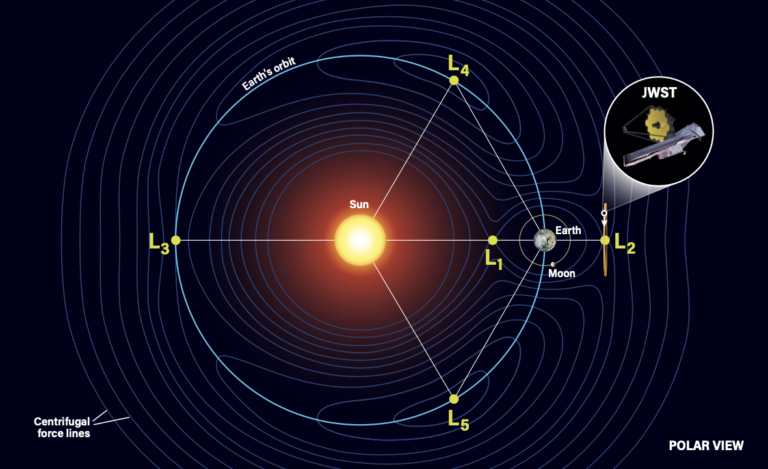

The first release of WISE data, covering about 80 percent of the sky, will be delivered to the astronomical community in May 2011. The mission scanned strips of the sky as it orbited around Earth’s poles since it launched last December. WISE always stays over Earth’s day-night line. As Earth moves around the Sun, new slices of sky come into the telescope’s field of view. It has taken 6 months, or the amount of time for Earth to travel halfway around the Sun, for the mission to complete one full scan of the entire sky.

For the next 3 months, the mission will map half of the sky again. This will enhance the telescope’s data, revealing more hidden asteroids, stars, and galaxies. The mapping will give astronomers a look at what has changed in the sky. The mission will end when the instrument’s block of solid hydrogen coolant, which is needed to chill its infrared detectors, runs out.

“The eyes of WISE have not blinked since launch,” said William Irace from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “Both our telescope and spacecraft have performed flawlessly and have imaged every corner of our universe, just as we planned.”

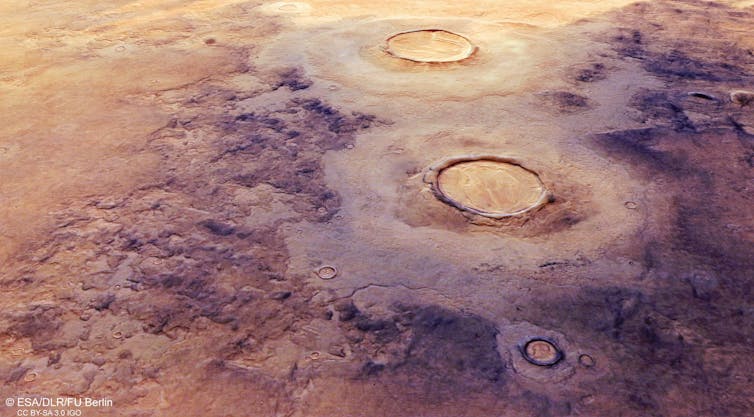

So far, WISE has observed more than 100,000 asteroids, both known and previously unseen. Most of these space rocks are in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter. However, some are near-Earth objects, asteroids, and comets with orbits that pass relatively close to Earth.

WISE has discovered more than 90 of these new near-Earth objects. The infrared telescope is also good at spotting comets that orbit far from Earth, and has discovered more than a dozen of these so far.

WISE’s infrared vision also gives it the unique ability to pick up the glow of cool stars, called brown dwarfs, in addition to distant galaxies bursting with light and energy. These galaxies are called ultraluminous infrared galaxies, and WISE can see the brightest of them.

“WISE is filling in the blanks on the infrared properties of everything in the universe from nearby asteroids to distant quasars,” said Peter Eisenhardt of JPL. “But the most exciting discoveries may well be objects we haven’t yet imagined exist.”