Supernovae were once a precious commodity — just five were recorded in the history of humanity until the first telescopes were built. Now, while scientists still thrill at what these exploding stars can reveal about the universe (dark energy’s dominance, for instance), individual finds are often taken for granted. But one particular supernova in a pair of colliding galaxies called Arp 299 took center stage Tuesday at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Nashville, Tennessee.

That’s because the supernova, found this past February, lies in a “super star cluster” that may host a million stars, each as massive as 20 suns, within a dense region of gas and dust. At 140 million light-years away, the cluster in one of the galaxies of Arp 299 is the closest of just 10 or so nearby super star clusters. But billions of light-years from Earth, these dense stellar nurseries are ubiquitous. At those distances, the universe looks as it did soon after the Big Bang, when galaxy mergers were more common and the cosmos was smaller and denser.

The two galaxies in Arp 299 share a tumultuous history. Almost a billion years ago they “passed by each other and messed each other up,” said Susan Neff, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and another of the researchers who found the supernova. Then, the galaxies had a second close encounter 6 million to 8 million years ago that compressed the gas and dust between them, creating super star clusters that gave birth to a new generation of massive stars. Now, scientists believe, those baby boomer stars should be reaching the end of their lives, detonating themselves in supernovae at an estimated rate of one every two years. (Normal galaxies host about one supernova per century.)

“I think the most exciting thing is seeing individual stars blow up because … you can learn details … like how massive they are,” said Daniel Weedman, an astronomer at Cornell University who likens the new result to being onstage at a nighttime concert. “You theorize thousands of people are out there, but if you see a flashbulb go off, that teaches us about people: some have cameras.”

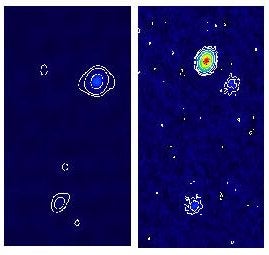

The discovery is as much a triumph for technology as it is for early universe studies. The dust and gas in which these stars and supernovae are embedded is so thick that only x rays and radio waves can penetrate it. But only the VLBA, whose linked telescopes have the resolution of a single dish spanning the distance from Hawaii to the U.S. Virgin Islands, can resolve the supernova and neighboring remnants.