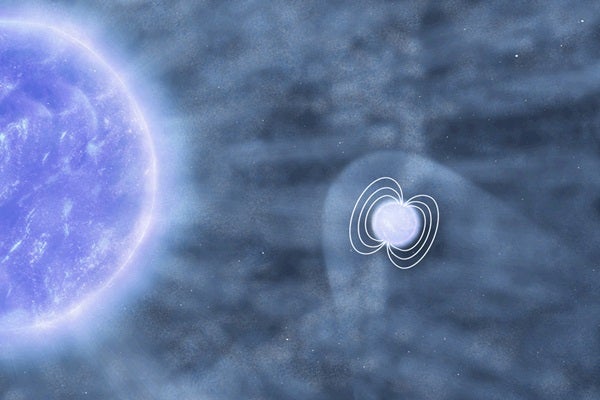

The flare took place on a neutron star, the collapsed heart of a once much larger star. Now about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in diameter, the neutron star is so dense that it generates a strong gravitational field.

The clump of matter was much larger than the neutron star and came from its enormous blue supergiant companion star.

“This was a huge bullet of gas that the star shot out, and it hit the neutron star allowing us to see it,” said Enrico Bozzo from University of Geneva, Switzerland.

The flare lasted 4 hours and the X-rays came from the gas in the clump as it was heated to millions of degrees while being pulled into the neutron star’s intense gravity field. In fact, the clump was so big that not much of it hit the neutron star. Yet, if the neutron star had not been in its path, this clump would probably have disappeared into space without a trace.

XMM-Newton caught the flare during a scheduled 12.5-hour observation of the system, which is known only by its catalog number IGR J18410-0535, but the astronomers were unaware of their catch.

The telescope works through a sequence of observations carefully planned to make the best use of the space observatory’s time, then sends the data to Earth.

It was about 10 days after the observation that Bozzo and his colleagues received the data and quickly realized they had something special. Not only were they pointing in the right direction to see the flare, but also the observation had lasted long enough for them to see it from beginning to end.

“I don’t know if there is any way to measure luck, but we were extremely lucky,” said Bozzo. He estimates that an X-ray flare of this magnitude can be expected a few times a year at the most for this particular star system.

The duration of the flare allowed them to estimate the size of the clump. It was much larger than the star, probably 10 million miles (16 million km) across, or about 100 billion times the volume of the Moon. Yet, according to the estimate made from the flare’s brightness, the clump contained only one-thousandth of our natural satellite’s mass.

These figures will help astronomers understand the behavior of the blue supergiant and the way it emits matter into space. All stars expel atoms into space, creating a stellar wind. The X-ray flare shows that this particular blue supergiant does it in a clumpy fashion, and the estimated size and mass of the cloud allow constraints to be placed on the process.

“This remarkable result highlights XMM-Newton’s unique capabilities,” comments Norbert Schartel, XMM-Newton Project Scientist. “Its observations indicate that these flares can be linked to the neutron star attempting to ingest a giant clump of matter.”

The flare took place on a neutron star, the collapsed heart of a once much larger star. Now about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in diameter, the neutron star is so dense that it generates a strong gravitational field.

The clump of matter was much larger than the neutron star and came from its enormous blue supergiant companion star.

“This was a huge bullet of gas that the star shot out, and it hit the neutron star allowing us to see it,” said Enrico Bozzo from University of Geneva, Switzerland.

The flare lasted 4 hours and the X-rays came from the gas in the clump as it was heated to millions of degrees while being pulled into the neutron star’s intense gravity field. In fact, the clump was so big that not much of it hit the neutron star. Yet, if the neutron star had not been in its path, this clump would probably have disappeared into space without a trace.

XMM-Newton caught the flare during a scheduled 12.5-hour observation of the system, which is known only by its catalog number IGR J18410-0535, but the astronomers were unaware of their catch.

The telescope works through a sequence of observations carefully planned to make the best use of the space observatory’s time, then sends the data to Earth.

It was about 10 days after the observation that Bozzo and his colleagues received the data and quickly realized they had something special. Not only were they pointing in the right direction to see the flare, but also the observation had lasted long enough for them to see it from beginning to end.

“I don’t know if there is any way to measure luck, but we were extremely lucky,” said Bozzo. He estimates that an X-ray flare of this magnitude can be expected a few times a year at the most for this particular star system.

The duration of the flare allowed them to estimate the size of the clump. It was much larger than the star, probably 10 million miles (16 million km) across, or about 100 billion times the volume of the Moon. Yet, according to the estimate made from the flare’s brightness, the clump contained only one-thousandth of our natural satellite’s mass.

These figures will help astronomers understand the behavior of the blue supergiant and the way it emits matter into space. All stars expel atoms into space, creating a stellar wind. The X-ray flare shows that this particular blue supergiant does it in a clumpy fashion, and the estimated size and mass of the cloud allow constraints to be placed on the process.

“This remarkable result highlights XMM-Newton’s unique capabilities,” comments Norbert Schartel, XMM-Newton Project Scientist. “Its observations indicate that these flares can be linked to the neutron star attempting to ingest a giant clump of matter.”