All galaxies are permeated by magnetic fields, including our Milky Way Galaxy. Despite intensive research, the origin of galactic magnetic fields is still unknown. Scientists assume, however, that they are built up by dynamo processes in which mechanical energy is converted into magnetic energy. Similar processes occur in the interior of Earth, the Sun, and — in the broadest sense — in the gadgets that power bicycle lights through peddling. By revealing the magnetic field structure throughout the Milky Way, the new map provides important insights into the machinery of galactic dynamos.

One way to measure cosmic magnetic fields, which has been known for more than 150 years, makes use of an effect known as Faraday rotation. When polarized light passes through a magnetized medium, the plane of polarization rotates. The amount of rotation depends, among other things, on the strength and direction of the magnetic field. Therefore, observing such rotation allows one to investigate the properties of the intervening magnetic fields.

To measure the magnetic field of our galaxy, radio astronomers observe the polarized light from distant radio sources, which passes through the Milky Way on its way to Earth. Scientists can deduce the amount of rotation due to the Faraday effect by measuring the polarization of the source at several frequencies.

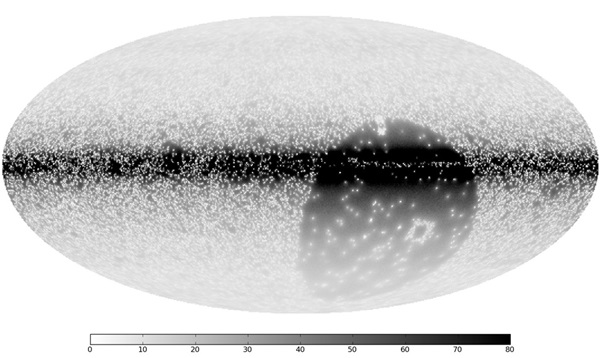

Even with so much data, coverage of the sky is still rather sparse. There remain large regions, especially in the southern sky, where so far only relatively few measurements have been made. Therefore, to obtain a realistic map of the entire sky, astronomers must interpolate between the existing data points. Here, two difficulties arise. First, the respective measurement accuracies vary greatly, and more precise measurements should have a greater influence. Also, the extent to which a single measurement point can provide reliable information about its surrounding environment is not known. Scientists must therefore infer this information from the data itself.

In addition, there is another problem. The measurement uncertainties are themselves uncertain owing to the highly complex measurement process. It so happens that the actual measurement error for a small but significant portion of the data can be more than 10 times as large as those indicated by the astronomers. The perceived accuracy of these outliers can strongly distort the resulting map if one does not correct for this effect.

To account for such problems, scientists at MPA have developed a new algorithm for image reconstruction called the “extended critical filter.” To derive this algorithm, the team makes use of the tools provided by the new discipline known as information field theory. Information field theory incorporates logical and statistical methods applied to fields, and it is a very powerful tool for dealing with inaccurate information. The approach is quite general and can be of benefit in a variety of image and signal-processing applications not only in astronomy, but also in other fields such as medicine or geography.

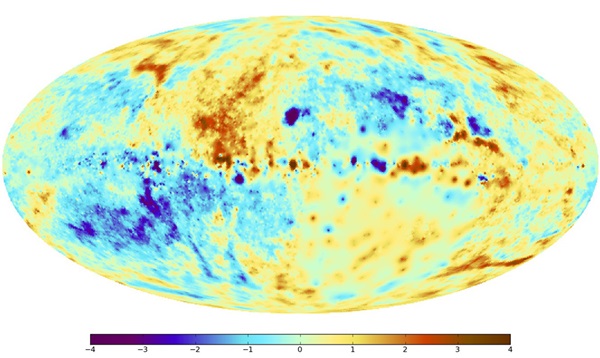

To better emphasize the structures in the galactic magnetic field, in Figure 3 the effect of the galactic disk has been removed so that weaker features above and below the galactic disk are more visible.

This reveals not only the conspicuous horizontal band of the gas disk of our Milky Way in the middle of the picture, but also that the magnetic field directions seem to be opposite above and below the disk. An analogous change of direction also takes place between the left and right sides of the image, from one side of the center of the Milky Way to the other.

A particular scenario in galactic dynamo theory predicts such symmetrical structures, which is supported by the newly created map. In this scenario, the magnetic fields are predominantly aligned parallel to the plane of the galactic disk in a circular or spiral configuration. The direction of the spiral is opposite above and below the galactic disk (Fig. 3). The observed symmetries in the Faraday map stem from our position within the galactic disk.

In addition to these large-scale structures, several smaller structures are apparent. These are associated with turbulent eddies and lumps in the highly dynamic gas of the Milky Way. The new map-making algorithm provides, as a by-product, a characterization of the size distribution of these turbulent structures, the so-called power spectrum. Larger structures are more pronounced than smaller, as is typical for turbulent systems. This spectrum can be directly compared with computer simulations of the turbulent gas and magnetic field dynamics in our galaxy, thus allowing for detailed tests of galactic dynamo models.

The new map is not only interesting for the study of our galaxy. Future studies of extragalactic magnetic fields will draw on this map to account for contamination from the galactic contribution. The next generation of radio telescopes, such as LOFAR, eVLA, ASKAP, Meerkat, and the SKA, are expected in the coming years and decades, and with them will come a wealth of new measurements of the Faraday effect. New data will prompt updates to the image of the Faraday sky. Perhaps this map will show the way to the hidden origin of galactic magnetic fields.