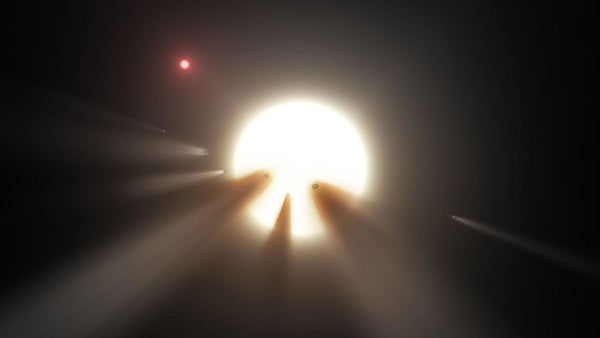

Let’s back up here. The basic summary of Tabby’s Star: hiding in Kepler data was a star with very, very unusual properties. Where planet-sized objects block out around 1 percent of light of the star, something around KIC 8462852 was blotting out more than 20 percent of the light. Not only that, but whatever it was wasn’t giving off the heat signature of an asteroid or dwarf planet.

There were a few hypothesizes for why this was. The most commonly accepted one is a swarm of comets or other icy debris. The least excepted but not-zero chance one was aliens. Further analysis showed no alien signals. Evidence for comets was inconclusive but sort of leaned towards the most probable answer thus far. But another factor came into play: a series of Harvard plates that showed a dimming over a period of a century on Tabby’s Star.

That’s where a Vanderbilt University-led team steps into the story, unraveling at least one part of the big mystery in a paper accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal: there’s no long-term dimming to account for. There are just some outside factors that made it seem like something more.

“At least for the idea that this is unprecedented … that doesn’t really hold up,” Michael Lund, a doctoral candidate at Vanderbilt and co-author of the paper, said. “We are finding this in other stars.”

All the data comes from the Digital Access to a Sky Century@Harvard, an archive of data collected by the university spanning from roughly 1885 to 1993. The initial study that utilized DASCH data didn’t account for one big fact about the DASCH data: it didn’t come from one telescope, but multiple telescopes. Changes in exposure and calibration could have introduced errors into the data.

“The telescopes changed over time,” Michael Lund, a doctoral candidate at Vanderbilt, said. “It’s an archive of photographic plates, but it’s using many telescopes.”

Up to 15 telescopes may have been part of the DASCH data. When laid out on a year-to-year basis, the stellar cycles show periods of dimming and brightening, much as would be expected for stars of its type. These cycles don’t correspond to an overall dimming trend. When the light curve of Tabby’s Star over this time is compared to stars whose light-and-dimming trends are more well known, those stars show a similar trend only in the Harvard records.

There’s also a 15 year gap in the data in the 1950s and 1960s, after which only one telescope was used. The dimming trend doesn’t continue after that gap. In other words, whatever showed the dimming of Tabby’s Star was an error in the data rather than an enigma in the star itself.

Lund is quick to point something out: this data in no way disproves that something weird is happening now around Tabby’s Star. It just shows that one hypothesis along the way was wrong.

“None of this changes the initial paper that noticed a very strange behavior,” Lund says. “None of this changes that that appears to be happening.”