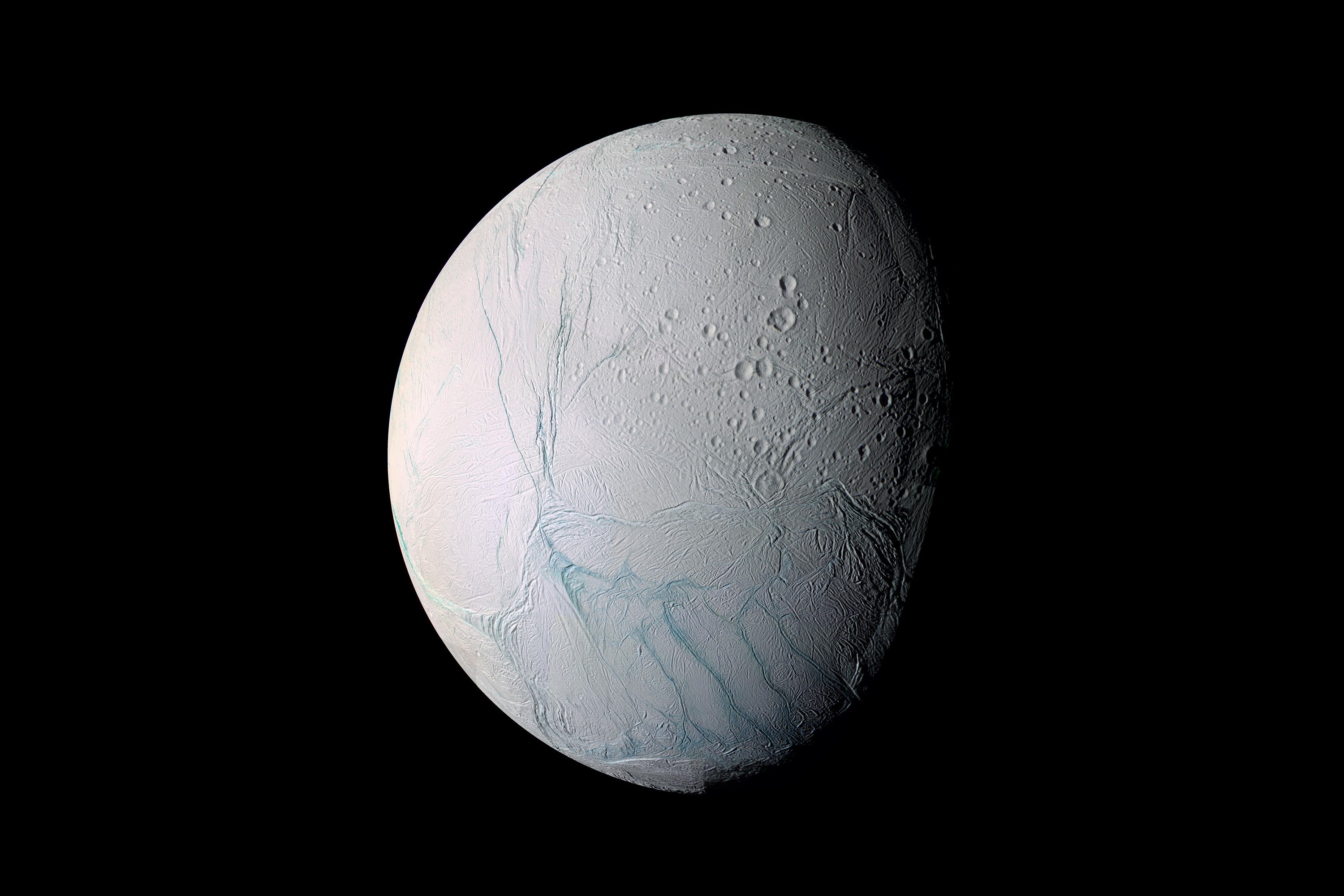

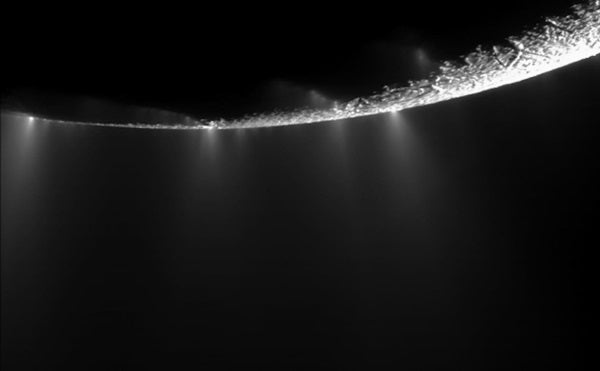

Seemingly sleepy Enceladus — a moon of Saturn’s just a fraction of the size of our own satellite — was barely on the radar of astronomers up until the Cassini mission arrived at the system in 2004. But close flybys in 2005 revealed one of the biggest solar system surprises: plumes of water erupting from underneath the ice shell, likely powered by a subsurface ocean.

Suddenly, Enceladus transformed from an odd, slightly puzzling snowball to one of the most exciting places for astrobiologists. That’s because where there’s water on Earth, there’s life. But a few other ingredients are also needed to make life. As a new study reveals in Nature Astronomy, though, Enceladus may have them. And more.

The paper examines data from Cassini and compares data from fly-throughs of Enceladus’ plumes to 50 chemical compounds the team suspected might be present in samples analyzed by one of Cassini’s instruments, its Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS). The research team then produced models comparing the data and found evidence for detections of a variety of important organic compounds.

“Searching for compounds in the plume is a bit like putting the pieces of a puzzle back together,” says lead author Jonah Peter, “in that we look for the right combination of molecules that reproduce the observed data. Information theory allows us to determine how much detail we can extract from the data without missing important features or overfitting to statistical noise.”

Water, ammonia, carbon dioxide, and methane had previously been found in analyses of INMS data, but this study found additional compounds and molecules, including acetylene, propylene, ethane, methanol, molecular oxygen, and hydrogen cyanide. These add to the various hints that Enceladus, despite its frigid perch in the outer solar system, harbors an environment conducive to life deep within its oceans.

Enceladus has a ‘key building block’

Hydrogen cyanide, despite its toxic-sounding name, may be one of the most important compounds confirmed with near certainty in the dataset. Peter calls it “a key building block for synthesizing more complex compounds related to the origin of life,” and says it could be a precursor to some of the proteins that compose DNA and RNA.

But various hydrocarbons are also exciting prospects for life, as they are often a substrate — or growth medium — for microbial life on Earth, helping to nourish really simple organisms.

Other potential detections also excite the researchers. First, there’s sulfur. The analysis found evidence for the existence of hydrogen sulfide, which you’ve certainly smelled before if you’ve ever whiffed a rotten egg. Hydrogen sulfide hints at geothermal activity within Enceladus, and geothermal vents play host to some of the most extreme life forms on Earth that happily thrive among them.

The team also potentially detected phosphorus, adding on to evidence of its presence on that moon. Both sulfur and phosphorus are important elements for life on Earth.

“Sulfur and phosphorus are two elements required for life, along with carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen,” Peter says. If the existence of sulfur is confirmed — phosphorus was detected at Enceladus earlier this year — this knowledge will help to empower the building of an Enceladus explorer. However, none of these findings yet offer a “smoking gun” for the existence of life on Enceladus, as all can be produced by non-living means.

Peter says laboratory experiments could reveal if these elements and compounds could assemble into the building blocks of life by creating a mini-Enceladus. “We know that certain amino acids and nucleobases can form from [hydrogen cyanide] under Enceladus-like conditions, but what about other biomolecules?” he says.

Beyond that, a robotic mission might be the next explorative step. Enceladus is too small and remote for even the largest telescopes to determine anything about the existence of life. The present study, even if planetary scientists need to sit tight for a few decades to find any answers, makes Enceladus an even more intriguing possible habitat for microbial life.