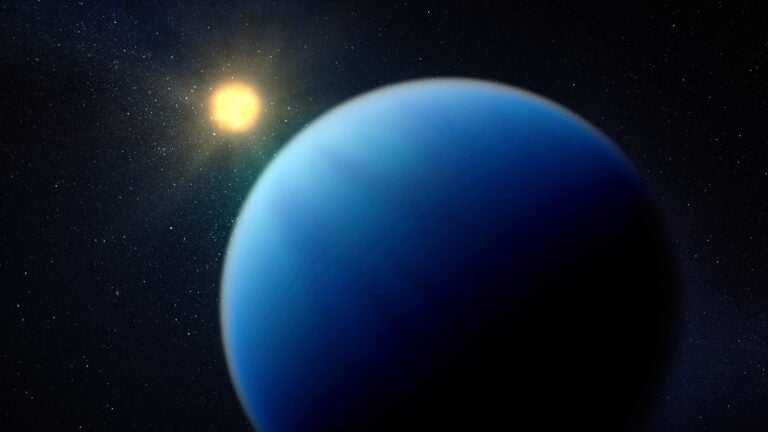

An international team of planet hunters has discovered as many as six low-mass planets around two nearby Sun-like stars, including two super-Earths with masses 5 and 7.5 times the mass of Earth. The researchers, led by Steven Vogt of the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), and Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, said the two super-Earths are the first ones found around Sun-like stars.

“These detections indicate that low-mass planets are quite common around nearby stars,” said Vogt, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCSC. “The discovery of potentially habitable nearby worlds may be just a few years away.”

The team found the new planet systems by combining data gathered at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii and the Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) in New South Wales, Australia.

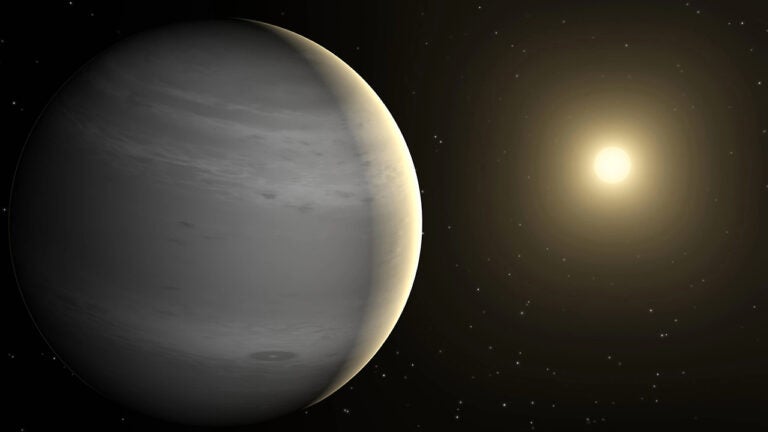

Three of the new planets orbit the bright star 61 Virginis (Vir), which can be seen with the naked eye under dark skies in the spring constellation Virgo. Astronomers and astrobiologists have long been fascinated with this particular star that is only 28 light-years away. Among hundreds of our nearest stellar neighbors, 61 Vir stands out as being the most nearly similar to the Sun in terms of age, mass, and other essential properties. Vogt and his collaborators have found that 61 Vir hosts at least three planets, with masses ranging from about 5 to 25 times the mass of Earth.

Recently, a separate team of astronomers used NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope to discover that 61 Vir also contains a thick ring of dust at a distance roughly twice as far from 61 Vir as Pluto is from our Sun. The dust is apparently created by collisions of comet-like bodies in the cold outer reaches of the system.

“Spitzer’s detection of cold dust orbiting 61 Vir indicates that there’s a real kinship between the Sun and 61 Vir,” said Eugenio Rivera, a researcher at the UCSC. Rivera computed an extensive set of numerical simulations to find that a habitable Earth-like world could easily exist in the as-yet unexplored region between the newly discovered planets and the outer dust disk.

According to Vogt, the planetary system around 61 Vir is an excellent candidate for study by the new Automated Planet Finder (APF) Telescope recently constructed at Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton near San Jose.

The second new system found by the team features a 7.5-Earth-mass planet orbiting HD 1461, another near-perfect twin of the Sun located 76 light-years away. At least one and possibly two additional planets also orbit the star. Lying in the constellation Cetus, HD 1461 can be seen with the naked eye in the early evening under good dark-sky conditions.

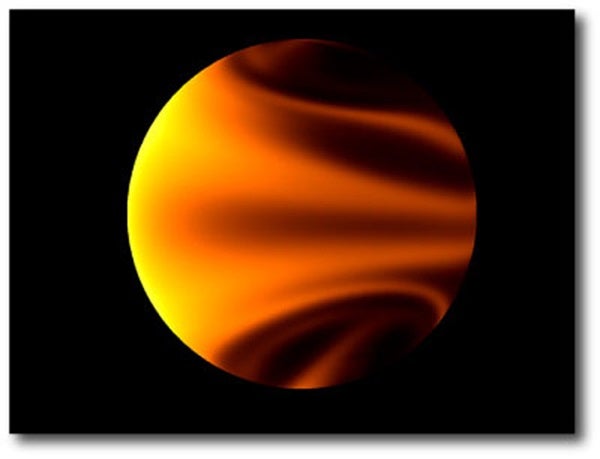

The 7.5-Earth-mass planet, assigned the name HD 1461b, has a mass nearly midway between the masses of Earth and Uranus. The researchers said they can’t tell yet if HD 1461b is a scaled-up version of Earth, composed largely of rock and iron, or whether, like Uranus and Neptune, it is composed mostly of water.

According to Butler, the new detections required state-of-the-art instruments and detection techniques. “The inner planet of the 61 Vir system is among the two or three lowest-amplitude planetary signals that have been identified with confidence,” he said. “We’ve found there is a tremendous advantage to be gained from combining data from the AAT and Keck telescopes, two world-class observatories, and it’s clear that we’ll have an excellent shot at identifying potentially habitable planets around the very nearest stars within just a few years.”

The 61 Vir and HD 1461 detections add to a slew of recent discoveries that have upended conventional thinking regarding planet detection. In the past year, it has become evident that planets orbiting the Sun’s nearest neighbors are extremely common. According to Butler, current indications are that one-half of nearby stars have a detectable planet with mass equal to or less than Neptune’s.

The Lick-Carnegie Exoplanet Survey Team led by Vogt and Butler uses radial velocity measurements from ground-based telescopes to detect the “wobble” induced in a star by the gravitational tug of an orbiting planet. The radial-velocity observations were complemented with precise brightness measurements acquired with robotic telescopes in Arizona by Gregory Henry of Tennessee State University.

“We don’t see any brightness variability in either star,” said Henry. “This assures us that the wobbles really are due to planets and not changing patterns of dark spots on the stars.”

Due to improvements in equipment and observing techniques, these ground-based methods are now capable of finding Earth-mass objects around nearby stars, according to team member Gregory Laughlin, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCSC.

“It’s come down to a neck-and-neck race as to whether the first potentially habitable planets will be detected from the ground or from space,” Laughlin said. “A few years ago, I’d have put my money on space-based detection methods, but now it really appears to be a toss-up. What is truly exciting about the current ground-based radial velocity detection method is that it is capable of locating the very closest potentially habitable planets.”

The Lick-Carnegie Exoplanet Survey Team has developed a publicly available tool, the Systemic Console, which enables members of the public to search for the signals of extrasolar planets by exploring real data sets in a straightforward and intuitive way. This tool is available online at

www.oklo.org.