In an announcement March 8, members of the large international Daya Bay collaboration reported the last of three measurements that describe how the three types, or flavors, of neutrinos blend with one another, providing an explanation for their spooky morphing from one flavor to another — a phenomenon called neutrino oscillation.

The measurement makes possible new experiments that may help explain why the present universe is filled mostly with matter, and not equal parts of matter and antimatter that would have annihilated each other and leave behind nothing but energy. One theory is that a process shortly after the birth of the universe led to the asymmetry, but a necessary condition for this is the violation of charge-parity (CP) symmetry. If neutrinos and their antimatter equivalent, antineutrinos, oscillate differently, this could provide the explanation.

“The result is very exciting because it essentially allows us to compare neutrino and antineutrino oscillations in the future and see how different they are and hopefully have an answer to the question, ‘Why do we exist?’” said Kam-Biu Luk from the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley), and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

Researchers knew that if the observed third kind of oscillation were zero or near zero, it would make further study of matter-antimatter asymmetry difficult.

“This is a new type of neutrino oscillation, and it is surprisingly large,” said Yifang Wang from China’s Institute of High Energy Physics, who is the co-spokesperson and Chinese project manager of the Daya Bay experiment. “Our precise measurement will complete the understanding of the neutrino oscillation and pave the way for the future understanding of matter-antimatter asymmetry in the universe.”

“Berkeley has played a key role since day one in the Daya Bay experiment, one of the biggest experimental particle physics collaborations ever between the U.S. and China,” said Graham Fleming from UC Berkeley. “The large value of the mixing angle theta one-three from this experiment enables a very broad program of fundamental new physics, including the proposed Long Baseline Neutrino experiment at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in [South] Dakota.”

Using antineutrinos from Chinese nuclear reactors

The results come from the Daya Bay Reactor Anti-neutrino Experiment in Guangdong Province, China, near Hong Kong, which is a joint collaboration between scientists in the United States, China, the Czech Republic, Hong Kong, Russia, and Taiwan. The U.S. institutions include UC Berkeley and LBNL, as well as Brookhaven National Laboratory, the University of Wisconsin, and Caltech.

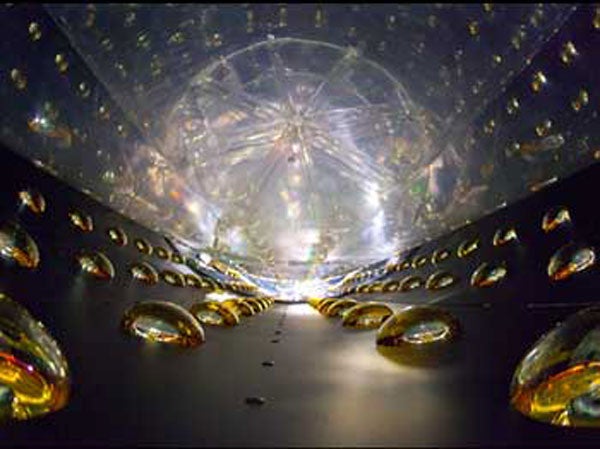

Nuclear power reactors at Daya Bay emit one kind or flavor of antineutrino — electron antineutrinos — that are identified in the six underground detectors. These detectors contain a liquid scintillator loaded with the element gadolinium. When the electron antineutrinos interact in the liquid, a blue glow is emitted.

Because some of the antineutrinos emitted by the reactors change flavor as they travel, the flux of electron antineutrinos measured in the detectors 1.1 miles (1.7 kilometers) from the reactor is less than the flux coming directly from the reactor and measured in the nearby detectors that are about 1,640 feet (500 meters) away. The deficit allowed scientists to determine the value of the mixing angle (theta one-three), the last to be measured of three mixing angles needed to interpret neutrinos’ flavor-changing behavior.

“Although we’re still two detectors shy of the complete experimental design, we’ve had extraordinary success in detecting the number of electron antineutrinos that disappear as they travel from the reactors to the detectors nearly 1.2 miles (two kilometers) away,” Luk said.

Neutrinos interact so weakly with other types of matter that they can pass through Earth as if it were not there. Once thought to be fairly boring, with zero mass and always traveling at the speed of light, neutrinos have proved to be a major challenge to the standard model of particle physics. Experiments over the past two decades showed that neutrinos do have mass and change their identity as they oscillate between three flavors: electron, muon, and tau.

Neutrinos’ shifting personalities require them to have at least some mass — probably less than one-millionth that of an electron — because that is what causes their strange identity problem. Each flavor of neutrino is a mixture of three different masses that fluctuate with time. Just as a white light composed of red, green, and blue shifts its tint as the proportions of each color changes, so the type of a neutrino changes as the proportions of the masses oscillate.

“Once a neutrino starts to propagate in space, it’s very hard to tell what its identity is until we remeasure it,” as in the Daya Bay experiment, Luk said.

Three numbers, called mixing angles, are part of the equations that describe these oscillations. The largest two were measured earlier in similar experiments, including the KamLand collaboration in which UC Berkeley and LBNL were active participants, but with detectors set hundreds of kilometers from the neutrino source. The oscillation period associated with the third mixing angle was expected to be so small that a much shorter baseline experiment was needed, hence the Daya Bay collaboration. The six power reactors at Daya Bay and nearby Ling Ao yield millions of quadrillions of electron antineutrinos every second, of which the six detectors recorded tens of thousands between December 24, 2011, and February 17, 2012.

Daya Bay will complete the installation of the remaining two detectors this summer to obtain more data about neutrino oscillations. As a result, Daya Bay will continue to have an interaction rate higher than three competing experiments in France, South Korea, and Japan, making it “the leading theta one-three experiment in the world,” said William Edwards from the physics department at UC Berkeley and LBNL.