NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft has provided new data on the Jupiter system — stunning scientists with never-before-seen perspectives of the giant planet’s atmosphere, rings, moons and magnetosphere.

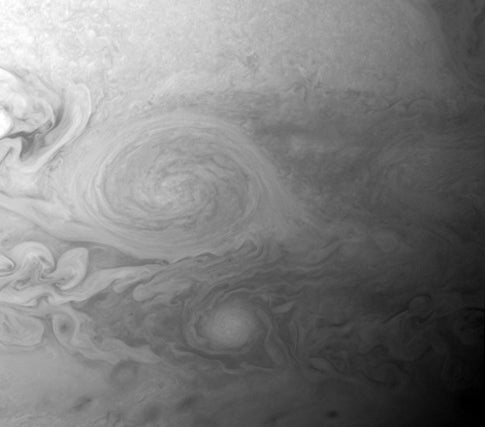

These new views include the closest peek yet at the Earth-sized “Little Red Spot” storm churning materials through Jupiter’s cloud tops; detailed images of small satellites herding dust and boulders through Jupiter’s faint rings; and of volcanic eruptions and circular grooves on the planet’s largest moons.

New Horizons came to within 1.4 million miles of Jupiter on February 28, using the planet’s gravity to trim three years off its travel time to Pluto. For several weeks before and after this closest approach, the piano-sized robotic probe trained its seven cameras and sensors on Jupiter and its four largest moons, storing data from nearly 700 observations on its digital recorders and gradually sending that information back to Earth. About 70 percent of the expected 34 gigabits of data has come back so far, radioed to NASA’s largest antennas over more than 600 million miles. This activity confirmed the successful testing of the instruments and operating software the spacecraft will use at Pluto.

“Aside from setting up our 2015 arrival at Pluto, the Jupiter flyby was a stress test of our spacecraft and team, and both passed with very high marks,” says New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, NASA Headquarters, Washington. “We’ll be analyzing this data for months to come; we have collected spectacular scientific products as well as evocative images.”

The spacecraft was 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Jupiter and 1.8 million miles (3 million km) from Europa when it captured the image.

“This is our best look ever of a storm like this in its infancy,” says Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), Laurel, Maryland, which built and operates the New Horizons spacecraft. “Combined with data from telescopes on and around Earth taken at the same time New Horizons sped past Jupiter, we’re getting an incredible look at the dynamics of weather on giant planets.”

Under a range of lighting and viewing angles, New Horizons also grabbed the clearest images ever of the tenuous Jovian ring system. In them, scientists spotted a series of arcs and clumps of dust, unexpected, they note, and indicative of a recent impact into the ring by a small object. Movies made from New Horizons images also provide an unprecedented look at ring dynamics, with the tiny inner moons Metis and Adrastea appearing to shepherd the materials around the rings.

“We’re starting to see that rings can evolve rapidly, with changes detectable over weeks and months,” says Jeff Moore, New Horizons Jupiter Encounter Science Team lead from NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif. “We’ve seen similar phenomena in the rings of Saturn.”

Of Jupiter’s four largest moons, the team focused much attention on volcanic Io, the most geologically active body in the solar system. New Horizons’ cameras captured pockets of bright, glowing lava scattered across the surface; dozens of small, glowing spots of gas; and several fortuitous views of a sunlit umbrella-shaped dust plume rising 200 miles into space from the volcano Tvashtar, the best images yet of a giant eruption from the tortured volcanic moon.

The timing and location of the spacecraft’s trajectory also allowed it to spy many of the mysterious, circular troughs carved onto the icy moon Europa. Data on the size, depth and distribution of these troughs, discovered by the Jupiter-orbiting Galileo mission, will help scientists determine the thickness of the ice shell that covers Europa’s global ocean.

Already the fastest spacecraft ever launched, New Horizons reached Jupiter just 13 months after lifting off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., in January 2006. The flyby added 9,000 miles per hour, pushing New Horizons past 50,000 miles per hour and setting up a flight by Pluto in July 2015.

The number of observations at Jupiter was twice that of those planned at Pluto. New Horizons made most of these observations during the spacecraft’s closest approach to the planet, which was guided by more than 40,000 separate commands in the onboard computer.

“We can run simulations and take test images of stars, and learn that things would probably work fine at Pluto,” says John Spencer, deputy lead of the New Horizons Jupiter Encounter Science Team, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. “But having a planet to look at and lots of data to dig into tells us that the spacecraft and team can do all these amazing things. We might not have explored the full capabilities of the spacecraft if we didn’t have this real planetary flyby to push the system and get our imaginations going.”

More data are to come, as New Horizons completes its unprecedented flight down Jupiter’s long magnetotail, analyzing the intensities of sun-charged particles that flow hundreds of millions of miles beyond the giant planet.