A Yale University analysis of one such event in a nearby galaxy provides an unprecedented look at the process. The research is described in the Astronomical Journal.

Specifically, Jeffrey Kenney from Yale, New Haven, Connecticut, looked at the way the cosmic wind is eroding the gas and dust at the leading edge of the galaxy. The wind, or ram pressure, is caused by the galaxy’s orbital motion through hot gas in the cluster. Kenney found a series of intricate dust formations on the disk’s edge, as cosmic wind began to work its way through the galaxy.

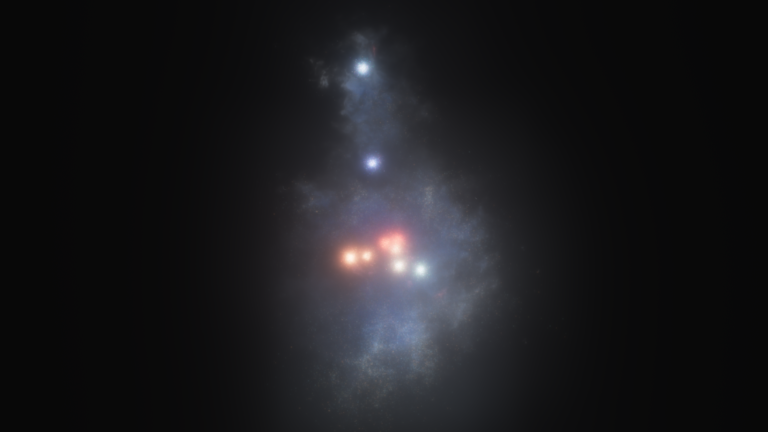

“On the leading side of the galaxy, all the gas and dust appears to be piled up in one long ridge, or dust front. But you see remarkable, fine scale structure in the dust front,” Kenney explained. “There are head-tail filaments protruding from the dust front. We think these are caused by dense gas clouds becoming separated from lower density gas.”

Cosmic wind can easily push low-density clouds of interstellar gas and dust, but not high-density clouds. As the wind blows, denser gas lumps start to separate from the surrounding lower density gas which gets blown downstream. But apparently, the high and low-density lumps are partially bound together, most likely by magnetic fields linking distant clouds of gas and dust.

“The evidence for this is that dust filaments in the Hubble Space Telescope image look like taffy being stretched out,” Kenney said. “We’re seeing this decoupling, clearly, for the first time.”

The analysis is based on Hubble images of a spiral galaxy in the Coma cluster, located 300 million light-years from Earth. It is the closest high-mass cluster to our solar system. Kenney first saw the images two years ago and realized their possible significance in understanding the way ram pressure strips interstellar material throughout the universe.

In the 1990s, a famous Hubble photo dubbed “Pillars of Creation” showed columns of dust and gas in the Eagle Nebula that were in the process of forging new stars. The dust filaments Kenney identified are similar in some ways to the “Pillars of Creation,” except they are 1,000 times larger.

In both cases, destruction is at least as important as creation. An external force is pushing away most of the gas and dust, therefore destroying most of the cloud, leaving behind only the most dense material — the pillars. But even the pillars don’t last that long.

Because gas is the raw material for star formation, its removal stops the creation of new stars and planets. In the Eagle Nebula, the pressure arises from intense radiation emitted by nearby massive stars; in the Coma galaxy, it is pressure from the galaxy’s orbital motion through hot gas in the cluster. Although new stars are being born in both kinds of pillars, we are witnessing, in both, the last generation of stars that will form.

Much of Kenney’s research has focused on the physical interplay of galaxies with their environment.

“A great deal of galaxy evolution is driven by interactions,” Kenney said. “Galaxies are shaped by collisions and mergers, as well as this sweeping of their gas from cosmic winds. I’m interested in all of these processes.”