Astronomers will peer deep into the universe in five directions to document the early history of star formation and galaxy evolution in an ambitious new project requiring an unprecedented amount of time on the Hubble Space Telescope.

By imaging more than 250,000 distant galaxies, the project will provide the first comprehensive view of the structure and assembly of galaxies over the first third of cosmic time. It will also yield crucial data on the earliest stages in the formation of supermassive black holes and find distant supernovae important for understanding dark energy and the accelerating expansion of the universe.

Project leader Sandra Faber, in the Astronomy and Astrophysics Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, (UCSC) said the effort relies on Hubble’s powerful new infrared camera, the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), as well as the telescope’s Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). The proposal, which brings together a large international team of collaborators, was awarded a record 902 orbits of observing time as one of three large-scale projects chosen for the Hubble Multi-Cycle Treasury Program. The observing time, totaling about three and a half months, will be spread out over the next two to three years.

“This is an effort to make the best use of Hubble while it is at the apex of its capabilities, providing major legacy data sets for the ages,” said Faber.

The committee that reviewed proposals for the Hubble Multi-Cycle Treasury Program asked Faber to combine her initial proposal with a similar one led by Henry Ferguson, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) that operates the Hubble telescope. Faber and Ferguson will work together to manage the project that involves more than 100 investigators from dozens of institutions around the world.

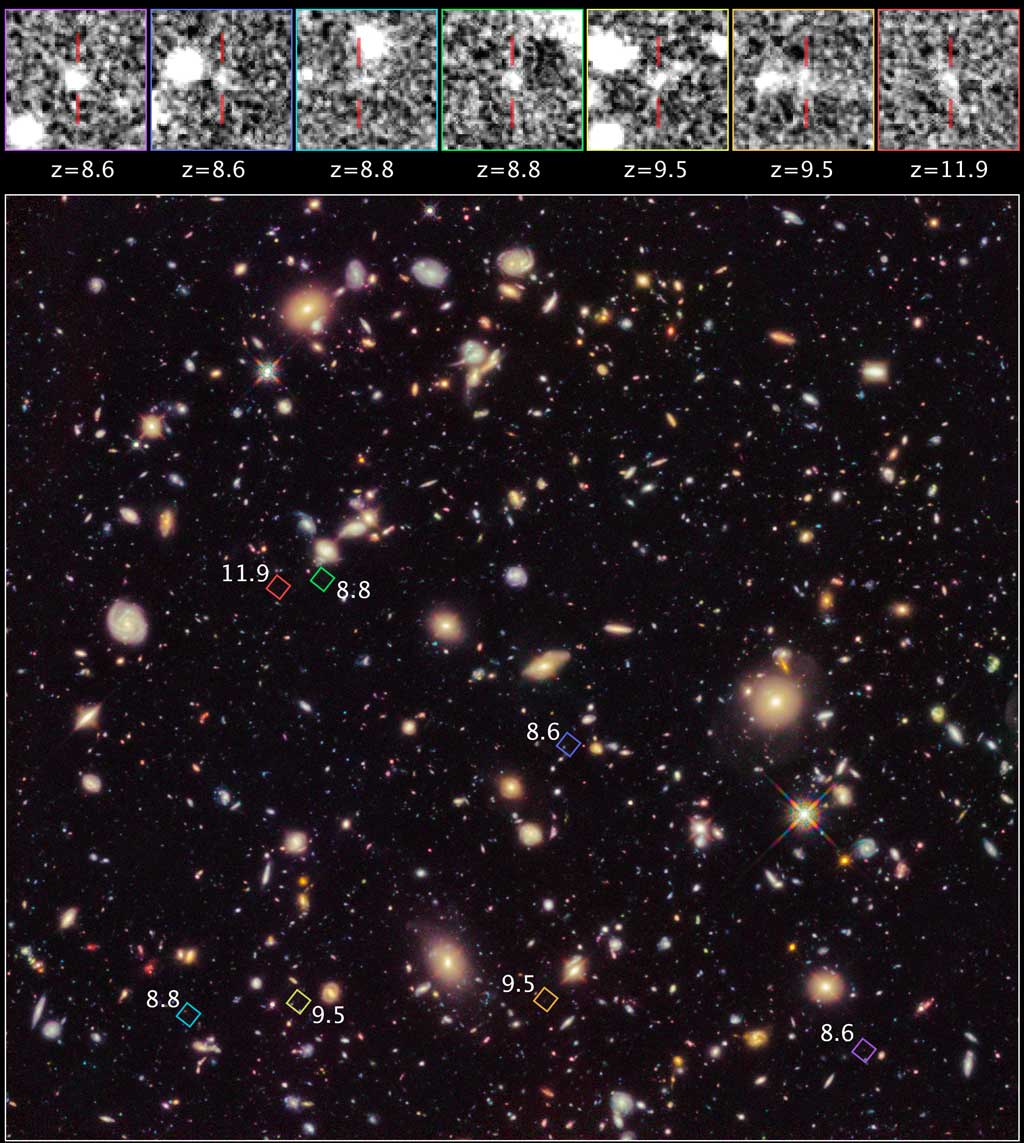

A powerful telescope like Hubble allows astronomers to see back in time as it gathers light that has traveled for billions of years across the universe. The new survey is designed to observe galaxies at distances that correspond to “look-back times” from nearly 13 billion years ago (about 600,000 years after the Big Bang) up to about 9 billion years ago. Astronomers express these distances in terms of redshift (“z”), a measure of how the expansion of the universe shifts the light from an object to longer wavelengths. The redshift increases with distance, and this study will look at objects at distances from about z=1.5 to z=8.

“We want to look very deep, very far back in time, and see what galaxies and black holes were doing back then,” Faber said. “It’s important to observe in different regions because the universe is very clumpy, and to have a large enough sample to count things so we can see how many of one kind of object versus another kind there were at different times.”

One of Faber’s colleagues at UCSC, Garth Illingworth, recently demonstrated the power of Hubble’s new camera when his team described the most distant galaxies detected. Illingworth’s team focused on one small patch of sky known as the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. Faber’s team will look both “deep” and “wide” to collect observations of a large number of distant objects in different regions of the sky.

The new data will be used to answer many key questions about galaxy evolution and cosmology. By studying how galaxy masses, morphologies, and star formation rates changed over time, researchers can test theories of galaxy formation and evolution.

“The earliest galaxies we see are truly infant galaxies. We want to know when massive galaxies first appeared, and when they started to look like the beautiful spiral galaxies we see today,” Faber said. “This study will allow us to chart for the first time the maturation process of galaxies.”

Of all the stars that have formed in the universe, only about 1 percent had formed by the time of the most distant epoch included in the survey. “When you combine our data with closer Hubble surveys, the telescope now covers 99 percent of all star formation in the universe,” Faber said. “All but the very first moments of galaxy evolution will be revealed.”

The study focuses on several patches of sky where deep observations with other instruments are providing data in multiple wavelengths of light, including x-ray data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. X-ray emissions reveal the presence of a supermassive black hole at the core of a galaxy powering an active galactic nucleus. Understanding the role of black holes in the evolution of galaxies is an important aspect of this project, Faber said.

“We don’t know if the black holes form later or are a central feature of these galaxies from the very beginning. We hope to observe the earliest stages of black hole growth,” she said.

Another important component of the project is the search for distant examples of a particular type of exploding star known as a Type Ia supernova. Astronomers have used the uniform brightness of these supernovae to measure cosmic distances, leading to the conclusion that a mysterious force called dark energy is accelerating the expansion of the universe. Observations of distant Type Ia supernovae will enable researchers to verify that their brightness are indeed uniform and to measure more accurately how the rate of expansion of the universe has changed over time.

Faber and her fellow astronomers expect the first data from their observations to be available by the end of the year. Data from this project will be made available to the entire astronomy community with no proprietary period for Faber’s team to conduct their own analysis. The likely result will be a race among teams of scientists to publish the first results from this new treasure trove of data. Faber said the project would yield such rich data it will keep astronomers busy for years to come.

“We’re very excited, not only about the 900 orbits, but also about what this new camera can do. It’s just amazing what it sees,” Faber said. “This project is the biggest event in my career, the culmination of three decades of work using big telescopes to study galaxy evolution.”