When low- to middle-weight stars like our Sun approach the end of their lives, they eventually become dense white dwarf stars. In doing so, they cast off their outer layers of dust and gas into space, creating a kaleidoscope of intricate patterns known as planetary nebulae.

These actually have nothing to do with planets, but were named in the late 18th century by astronomer William Herschel because they appeared as fuzzy circular objects through his telescope, somewhat like the planets in our solar system.

Over two centuries later, planetary nebulae studied with William Herschel’s namesake, the Herschel Space Observatory, have yielded a surprising discovery. Like the dramatic supernova explosions of weightier stars, the death cries of the stars responsible for planetary nebulae also enrich the local interstellar environment with elements from which the next generations of stars are born.

While supernovae are capable of forging the heaviest elements, planetary nebulae contain a large proportion of the lighter “elements of life,” such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen made by nuclear fusion in the parent star.

A star like the Sun steadily burns hydrogen in its core for billions of years. But once the fuel begins to run out, the central star swells into a red giant, becoming unstable and shedding its outer layers to form a planetary nebula.

The remaining core of the star eventually becomes a hot white dwarf pouring out ultraviolet radiation into its surroundings.

This intense radiation may destroy molecules that had previously been ejected by the star and that are bound up in the clumps or rings of material seen in the periphery of planetary nebulae.

The harsh radiation was also assumed to restrict the formation of new molecules in those regions.

But in two separate studies using Herschel, astronomers have discovered that a molecule vital to the formation of water seems to rather like this harsh environment and perhaps even depends upon it to form. The molecule, known as OH+, is a positively charged combination of single oxygen and hydrogen atoms.

In one study, led by Isabel Aleman of the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, 11 planetary nebulae were analyzed, and the molecule was found in just three.

What links the three is that they host the hottest stars, with temperatures exceeding (180,000° Fahrenheit) 100,000º Celsius.

“We think that a critical clue is in the presence of the dense clumps of gas and dust, which are illuminated by UV and X-ray radiation emitted by the hot central star,” said Aleman. “This high-energy radiation interacts with the clumps to trigger chemical reactions that leads to the formation of the molecules.”

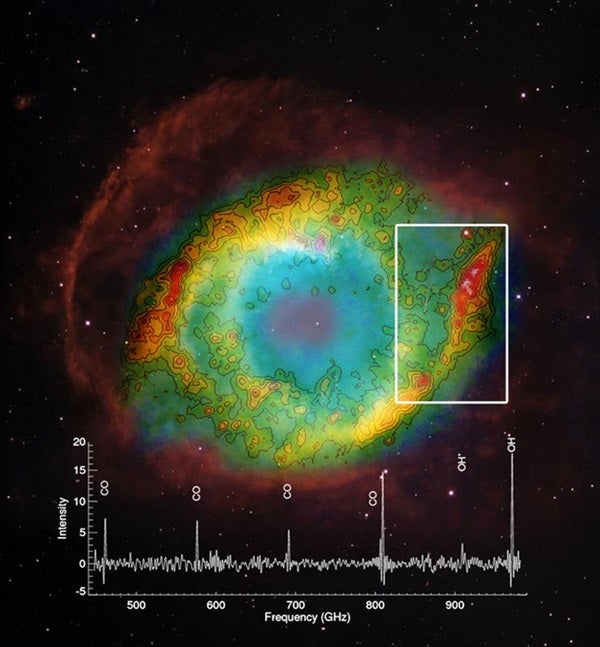

Meanwhile, another study, led by Mireya Etxaluze of the Instituto de Ciencia de los Materiales de Madrid, Spain, focused on the Helix Nebula, one of the nearest planetary nebulae to our solar system at a distance of 700 light-years.

The central star is about half the mass of our Sun but has a far higher temperature of about 216,000° F (120,000º C). The expelled shells of the star, which in optical images appear reminiscent of a human eye, are known to contain a rich variety of molecules.

Herschel mapped the presence of the crucial molecule across the Helix Nebula and found it to be most abundant in locations where carbon monoxide molecules, previously ejected by the star, are most likely to be destroyed by the strong UV radiation.

Once oxygen atoms have been liberated from the carbon monoxide, they are available to make the oxygen–hydrogen molecules, further bolstering the hypothesis that the UV radiation may be promoting their creation.

The two studies are the first to identify in planetary nebulae this critical molecule needed for the formation of water, although it remains to be seen if the conditions would actually allow water formation to proceed.

“The proximity of the Helix Nebula means we have a natural laboratory on our cosmic doorstep to study in more detail the chemistry of these objects and their role in recycling molecules through the interstellar medium,” said Etxaluze.

“Herschel has traced water across the universe from star-forming clouds to the asteroid belt in our own solar system,” said Göran Pilbratt from ESA. “Now we have even found that stars like our Sun could contribute to the formation of water in the universe, even as they are in their death throes.”