White dwarfs are the cooling Earth-size cores of dead stars left behind after average-size stars have exhausted their fuel and shed their outer layers. Our Sun will eventually fade into a white dwarf after first bloating to become a red giant. The same fate awaits more than 90% of the stars in our galaxy.

Previous research has found the remains of worlds that disintegrated when the progenitor stars of white dwarfs engulfed nearby planets during their red giant phase. This raised the question of whether any worlds might avoid this destruction and end up orbiting the resulting white dwarfs.

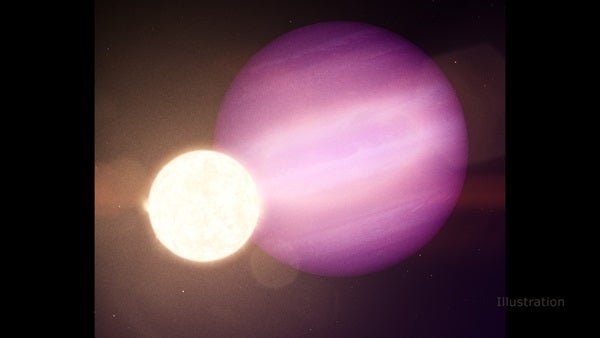

In the new study, astronomers investigated a white dwarf in the constellation Draco about 81.5 light-years from Earth. Using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and other telescopes, they discovered the dead star was orbited by a roughly planet-size body dubbed WD 1586 b, which has a mass at most 14 times that of Jupiter and a diameter about 10 times that of the white dwarf.

The researchers suggest that in order to avoid obliteration when the progenitor star evolved into a red giant, WD 1586 b must have originally orbited its star farther away than the distance between Earth and the Sun. Later, gravitational interactions with other worlds in the remnant planetary system flung WD 1586 b into a closer orbit. It is now nearly 20 times closer to the white dwarf than Mercury is to the Sun, completing an orbit every 34 hours.

“If a giant planet survived the journey close to a white dwarf, then it means that smaller planets could as well,” said study lead author Andrew Vanderburg, an astronomer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Although white dwarfs no longer burn fuel, they can still remain hot for billions of years. Vanderburg noted that “if a rocky planet made a similar journey to the planet we discovered, it could end up in the habitable zone of the white dwarf,” the area around a star temperate enough to host water, and potentially life as we know it.

All in all, these findings “could offer a way for a white dwarf to give rise to a second generation of life in a planetary system, long after the star ran out of hydrogen fuel and died,” Vanderburg said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Sept. 17 issue of the journal Nature.

This article is republished from Inside Science under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.