“We essentially created a virtual Beta Pictoris in the computer and watched it evolve over millions of years,” said Erika Nesvold from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “This is the first full 3-D model of a debris disk where we can watch the development of asymmetric features formed by planets, like warps and eccentric rings, and also track collisions among the particles at the same time.”

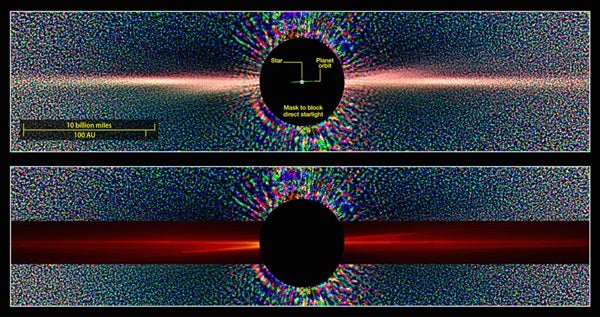

In 1984, Beta Pictoris became the second star known to be surrounded by a bright disk of dust and debris. Located only 63 light-years away, Beta Pictoris is an estimated 21 million years old, or less than 1 percent the age of our solar system. It offers astronomers a front-row seat to the evolution of a young planetary system, and it remains one of the closest, youngest, and best-studied examples today. The disk, which we see edge on, contains rock and ice fragments ranging in size from objects larger than houses to grains as small as smoke particles. It’s a younger version of the Kuiper Belt at the fringes of our planetary system.

Nesvold and her colleague Marc Kuchner from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, presented the findings Thursday during the “In the Spirit of Lyot 2015” conference in Montreal, which focuses on the direct detection of planets and disks around distant stars.

In 2009, astronomers confirmed the existence of Beta Pictoris b, a planet with an estimated mass of about nine times Jupiter’s, in the debris disk around Beta Pictoris. Traveling along a tilted and slightly elongated 20-year orbit, the planet stays about as far away from its star as Saturn does from our Sun.

Astronomers have struggled to explain various features seen in the disk, including a warp apparent at submillimeter wavelengths, an X-shaped pattern visible in scattered light, and vast clumps of carbon monoxide gas. A common ingredient in comets, carbon monoxide molecules are destroyed by ultraviolet starlight in a few hundred years. To explain why the gas is clumped, previous researchers suggested the clumps could be evidence of icy debris being corralled by a second as-yet-unseen planet, resulting in an unusually high number of collisions that produce carbon monoxide. Or perhaps the gas was the aftermath of an extraordinary crash of icy worlds as large as Mars.

“Our simulation suggests many of these features can be readily explained by a pair of colliding spiral waves excited in the disk by the motion and gravity of Beta Pictoris b,” Kuchner said. “Much like someone doing a cannonball in a swimming pool, the planet drove huge changes in the debris disk once it reached its present orbit.”

Keeping tabs on thousands of fragmenting particles over millions of years is a computationally difficult task. Existing models either weren’t stable over a sufficiently long time or contained approximations that could mask some of the structure Nesvold and Kuchner were looking for.

Working with Margaret Pan and Hanno Rein, both now at the University of Toronto, they developed a method where each particle in the simulation represents a cluster of bodies with a range of sizes and similar motions. By tracking how these “superparticles” interact, they could see how collisions among trillions of fragments produce dust and, combined with other forces in the disk, shape it into the kinds of patterns seen by telescopes. The technique, called the Superparticle-Method Algorithm for Collisions in Kuiper belts (SMACK), also greatly reduces the time required to run such a complex computation.

Using the Discover supercomputer operated by the NASA Center for Climate Simulation at Goddard, the SMACK-driven Beta Pictoris model ran for 11 days and tracked the evolution of 100,000 superparticles over the lifetime of the disk.

As the planet moves along its tilted path, it passes vertically through the disk twice each orbit. Its gravity excites a vertical spiral wave in the disk. Debris concentrates in the crests and troughs of the waves and collides most often there, which explains the X-shaped pattern seen in the dust and may help explain the carbon monoxide clumps.

The planet’s orbit also is slightly eccentric, which means its distance from the star varies a little every orbit. This motion stirs up the debris and drives a second spiral wave across the face of the disk. This wave increases collisions in the inner regions of the disk, which removes larger fragments by grinding them away. In the real disk, astronomers report a similar clearing out of large debris close to the star.

“One of the nagging questions about Beta Pictoris is how the planet ended up in such an odd orbit,” Nesvold said. “Our simulation suggests it arrived there about 10 million years ago, possibly after interacting with other planets orbiting the star that we haven’t detected yet.”