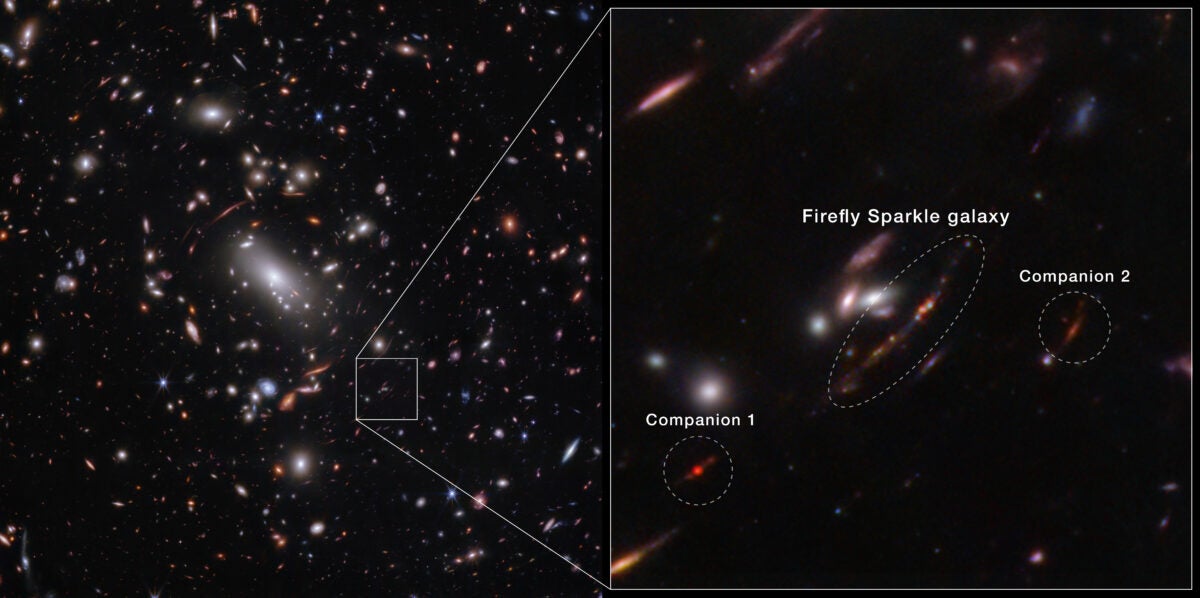

Gravitational lensing (an effect that causes distant objects to be magnified or stretched by the gravity of a large object along their line of sight) is one of astronomers’ most useful observing tools. In work published earlier this month, a group of astronomers and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) used this technique to their advantage to detect and resolve an unprecedented find — a young lightweight, early Milky Way lookalike that is still actively forming.

This galaxy existed when the universe was only 600 million years old — just 5 percent of its current age. What makes this particular galaxy so extraordinary is that most galaxies found at this time are far more massive. Another astonishing feature of this galaxy is that it sports 10 gleaming star clusters, which gave the galaxy its whimsical name: the Firefly Sparkle Galaxy.

“I didn’t think it would be possible to resolve a galaxy that existed so early in the universe into so many distinct components, let alone find that its mass is similar to our own galaxy’s when it was in the process of forming,” said Lamiya Mowla, co-lead author of the paper and an assistant professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, in a press release. “There is so much going on inside this tiny galaxy, including so many different phases of star formation.”

Working backwards

The Firefly Sparkle was previously imaged by Hubble Space Telescope and Keck Observatory, but was followed-up using the power of both gravitational lensing and multi-wavelength data from JWST’s CAnadian NIRISS Unbiased Cluster Survey (CANUCS). The role of the lens was played by the massive galaxy cluster called MACS J1423.8 + 2404, which lies between us and the Firefly Sparkle.

“Without the benefit of this gravitational lens, we would not be able to resolve this galaxy,” said Kartheik Iyer, a co-lead author of the paper, in a press release. “We knew to expect it based on current physics, but it’s surprising that we actually saw it.”

In the team’s paper, published in Nature on Dec. 11, they created a model to “undo” the visual distortions of the lensing. It turns out that the Firefly Sparkle’s original form appears like a stretched raindrop; its stars have not yet settled into either the central bulge or a thin disk. In other words, the galaxy is still very much in the process of forming.

Sparkling firework

The 10 distinct star clusters appear in various shades of pink, purple, and blue. This indicates that the stars in them have different ages and formed at different times — a conclusion backed up by analysis of their spectra. “Each clump of stars is undergoing a different phase of formation or evolution,” said Chris Willow, a co-author and the observation program’s principal investigator.

The team also discovered that the Firefly Sparkle has two galaxy companions (with similarly playful names of Firefly-Best Friend and Firefly-New Best Friend) that are just “hanging out,” as the press release states. One is only 6,500 light-years away from the Firefly Sparkle and the second is 42,000 light-years away. The interactions between the three systems are what the galaxy needs to activate star formation, and cause the gas to condense, cool, and form clumps.

Astronomers don’t know how the Firefly Sparkle will evolve over the next few billions of years. But around the cosmic time that we are seeing the Firefly Sparkle, Milky Way-like galaxy progenitors were about 10,000 times less massive than today’s Milky Way. Hopefully with the collaboration of observatories and surveys, researchers can discover other similar lightweight galaxies. These type of discoveries can tell us more about the early formative stages of galaxies similar to our Milky Way.