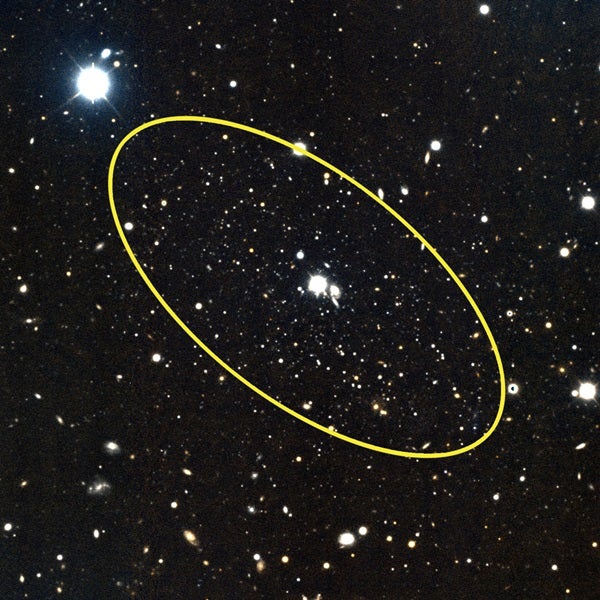

Eric Bell and Colin Slater found Andromeda XXVIII and XXIX. They did it by using a tested star-counting technique on the newest data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which has mapped more than a third of the night sky. They also used follow-up data from the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii.

At 1.7 million light-years from Andromeda, these are two of the furthest satellite galaxies ever detected. Invisible to the naked eye, the galaxies are 100,000 times fainter than Andromeda and are barely visible even through large telescopes.

These astronomers set out looking for dwarf galaxies around Andromeda to help them understand how matter relates to dark matter, an invisible substance that doesn’t emit or reflect light, but is believed to make up most of the universe’s mass. Astronomers believe it exists because they can detect its gravitational effects on visible matter. With its gravity, dark matter is believed to be responsible for organizing visible matter into galaxies.

“These faint, dwarf, relatively nearby galaxies are a real battleground in trying to understand how dark matter acts at small scales,” Bell said. “The stakes are high.”

The prevailing hypothesis is that visible galaxies are all nestled in beds of dark matter, and each bed of dark matter has a galaxy in it.

For a given volume of universe, the predictions match observations of large galaxies.

“But it seems to break down when we get to smaller galaxies,” Slater said. “The models predict far more dark matter halos than we observe galaxies. We don’t know if it’s because we’re not seeing all of the galaxies or because our predictions are wrong.”

“The exciting answer,” Bell said, “would be that there just aren’t that many dark matter halos. This is part of the grand effort to test that paradigm.”

Eric Bell and Colin Slater found Andromeda XXVIII and XXIX. They did it by using a tested star-counting technique on the newest data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which has mapped more than a third of the night sky. They also used follow-up data from the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii.

At 1.7 million light-years from Andromeda, these are two of the furthest satellite galaxies ever detected. Invisible to the naked eye, the galaxies are 100,000 times fainter than Andromeda and are barely visible even through large telescopes.

These astronomers set out looking for dwarf galaxies around Andromeda to help them understand how matter relates to dark matter, an invisible substance that doesn’t emit or reflect light, but is believed to make up most of the universe’s mass. Astronomers believe it exists because they can detect its gravitational effects on visible matter. With its gravity, dark matter is believed to be responsible for organizing visible matter into galaxies.

“These faint, dwarf, relatively nearby galaxies are a real battleground in trying to understand how dark matter acts at small scales,” Bell said. “The stakes are high.”

The prevailing hypothesis is that visible galaxies are all nestled in beds of dark matter, and each bed of dark matter has a galaxy in it.

For a given volume of universe, the predictions match observations of large galaxies.

“But it seems to break down when we get to smaller galaxies,” Slater said. “The models predict far more dark matter halos than we observe galaxies. We don’t know if it’s because we’re not seeing all of the galaxies or because our predictions are wrong.”

“The exciting answer,” Bell said, “would be that there just aren’t that many dark matter halos. This is part of the grand effort to test that paradigm.”