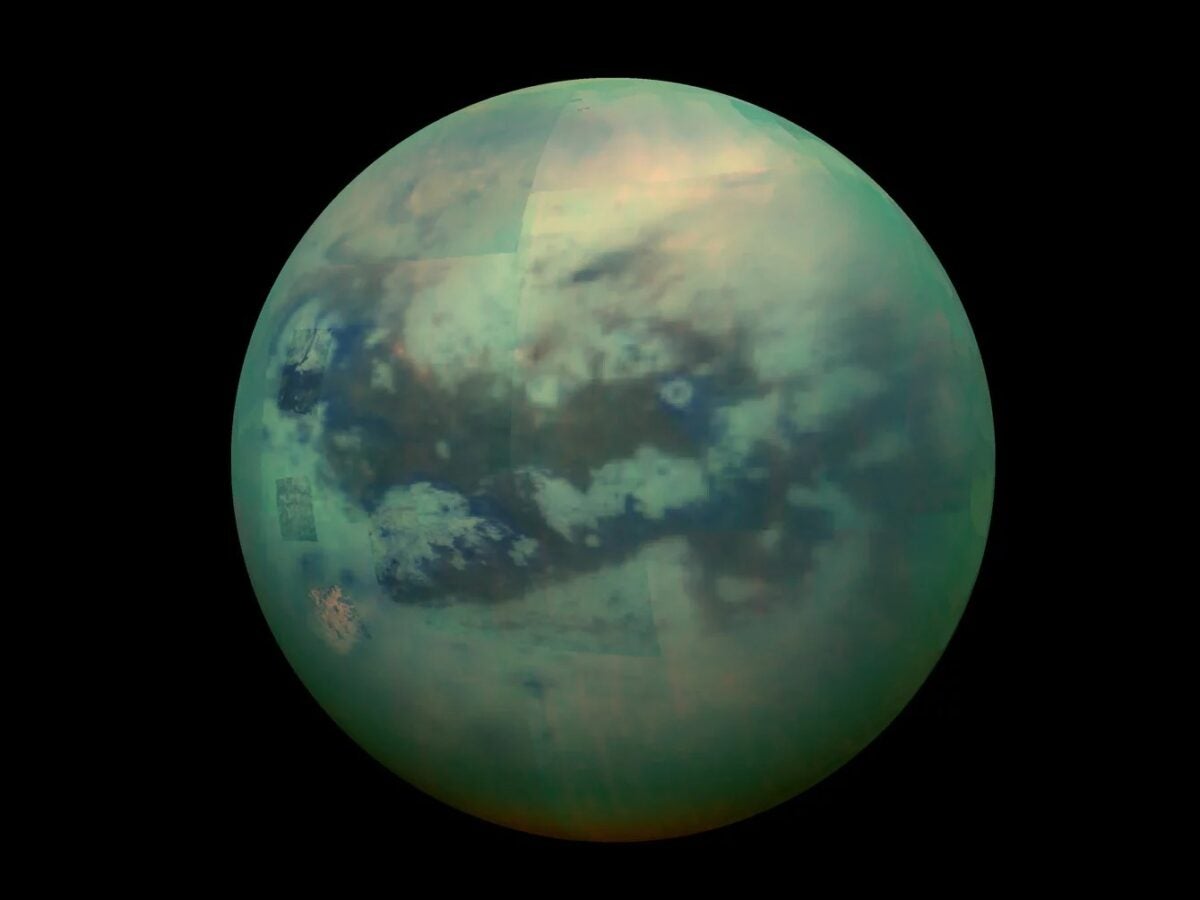

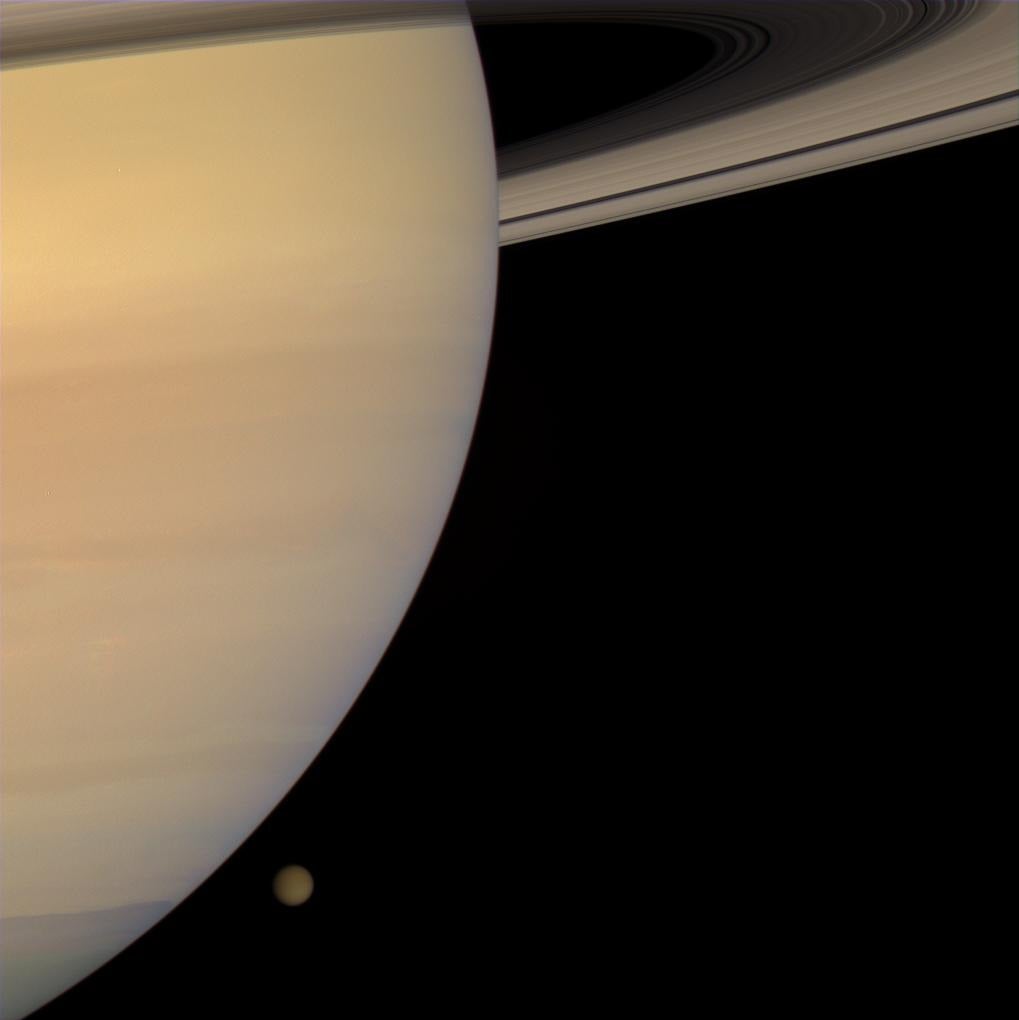

An international team of planetary scientists studied archival data from the Cassini spacecraft — designed to study Saturn and its satellites — which yielded new clues to three strange oceans on the surface of the planet’s largest moon, Titan.

The research, published in Nature Communications, gathered Cassini data taken through bistatic radar experiments between March 2006 and November 2016 during its egress phase (when the spacecraft is at its furthest) to piece together clues about Titan, the second largest moon of the solar system. They discovered evidence for wave activity and that the materials comprising the oceans aren’t equally proportional.

The team used data from the Radio Science Subsystem to create a bistatic radar system, where the receiver and the transmitter are placed far enough apart to gather some spatial data based on how the radio waves bounced off a target and are received back by the receiver — a sort of triangulation that can provide richer data than a conventional radar. But in this case, the receiver was NASA’s Deep Space Network on Earth.

Swimming over the surface

Titan is the only moon in the solar system with a substantial atmosphere, allowing liquid to pool on the surface. Although, it’s far too cold for water to exist at the surface as anything other than bedrock, so instead, the seas are composed of ethane and methane. The researchers looked at different densities of the bodies of liquid to determine the ratios of ethane and methane.

“I want to underline the difficulty that these experiments represented, because the experiment basically requires Cassini to point them at the surface of Titan and the reflection to be received back on Earth, one billion and a half kilometers away,” study author Valerio Poggiali of Cornell University says.

Related: What Cassini taught us | Why was Cassini crashed into Saturn?

“We also have indications that the rivers feeding the seas are pure methane,” said Poggiali in a press release, “until they flow into the open liquid seas, which are more ethane-rich.” So when these two liquids mix, the bodies differ in viscosity and density, even if it’s by some small amounts. This is an especially important find because NASA has funded studies to explore the possibility of someday using a submersible in the seas to study their depths and understand what interactions they may have with a subsurface liquid-water ocean, if any.

Titan is said to have a similar composition to early Earth. But regardless of the particular chemistry as it relates to potential life, it poses other mysteries: Where does the methane come from, and how does it replenish on the surface similar to the water cycle on Earth. This may be up to future missions to solve, such as the Dragonfly rotorcraft, a NASA-planned mission to examine the surface of Titan.

There also isn’t much ethane on the surface as would be expected, potentially meaning that it undergoes a similar cycle as Earth’s. “On the surface we don’t see, we would expect tons of [methane] covering the service, but it’s not the case. So, there must be places where all the ethane is sequestered and the methane is replenished,” Poggiali says. He added that there’s a possibility that cryovolcanism — where liquids protrude from below the surface out of icy bedrock — plays a role.

Unsurfable waves

Apart from the chemical composition, the team was able to get insight on the seas’ surface waves, as well as hints of tidal effects from Saturn. The waves were small on the bodies of water, hovering around 3.3 millimeters — quite far from surfing conditions. A larger uptick in height was observed where rivers meet the oceans, the roughest disturbance was about 5.2 mm, which could also point to tidal interactions. Poggiali compares the waves to “ripples on the surface because, as of today, large-scale waves have not been observed.”

This could also mean the waves have a minimal effect on coastal erosion along the shores of Titan’s beaches. Such minimal wave activity and hardly detectable tidal activity could be a boon for any future submersibles.

There’s still plenty of archival data from Cassini that could help unveil more details about Titan. A combination of that data and from the future Dragonfly mission could help solve some of the questions posed by the study — but will also likely raise a few more.