When seen with the human eye, Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is gray — all over. With its color filters, Rosetta’s scientific imaging system OSIRIS, however, can discern tiny differences in reflectivity. To this effect, scientists from the OSIRIS team image the same region on the comet’s surface using different color filters. If, for example, the region appears especially bright in one of these images, it reflects light of this wavelength especially well.

“Even though the color variations on 67P’s surface are minute, they can give us important clues,” said Holger Sierks from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany. In a recent analysis performed by the OSIRIS team, the Hapi region clearly stands out from the rest of the comet: While most parts of 67P display a slightly reddish reflectivity spectrum as is common for cometary nuclei and other primitive bodies, the reflection of red light is somewhat lower in this region.

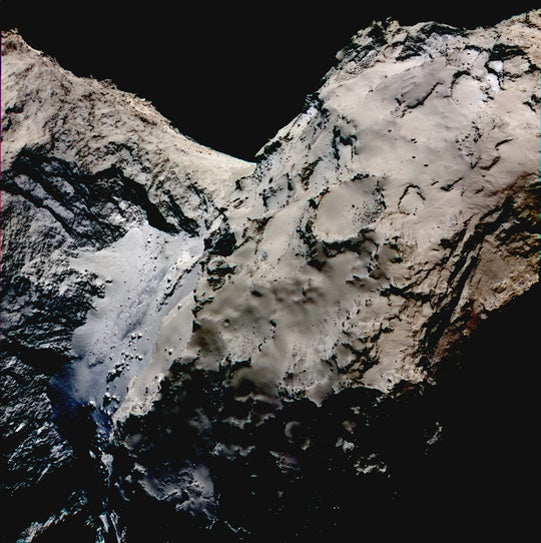

“We know that the reflectivity properties are closely correlated to the surface morphology,” said Sonia Fornasier from the Paris Observatory. Where the smooth surface of the Hapi region gives way to the more rugged terrain of the surrounding areas, the reflectivity, too, changes.

The scientists believe that Hapi’s special reflectivity properties hint at a higher abundance of frozen water at or near the surface. Earlier comet missions had observed similar behavior on comets 103P/Hartley 2 and 9P/Tempel 1 and associated the bluish spectrum to the presence of frozen water. While OSIRIS can only study a limited number of spectral bands, Rosetta is equipped with other instruments such as VIRTIS that can unambiguously identify the spectral signature of water molecules in infrared reflection. “We are excited to see whether our suspicion will be confirmed,” said Sierks.

The Hapi region differs from the rest of 67P’s surface in many respects. Not only is it much smoother, it is also one of the main sources of activity in the northern hemisphere. Early dust jets originated there. “During perihelion when 67P heats up significantly, Hapi is hidden in northern polar night. Outbound on the comet’s orbit, from March 2016, Hapi will receive solar heat again,” said Fornasier. “At this large distance from the Sun, it will then be very cold. Hapi might therefore be a region that has been able to retain ices on its surface during past orbits around the Sun and has thus enough “fuel” left to create the fireworks of activity we have witnessed in the past months.”