Key Takeaways:

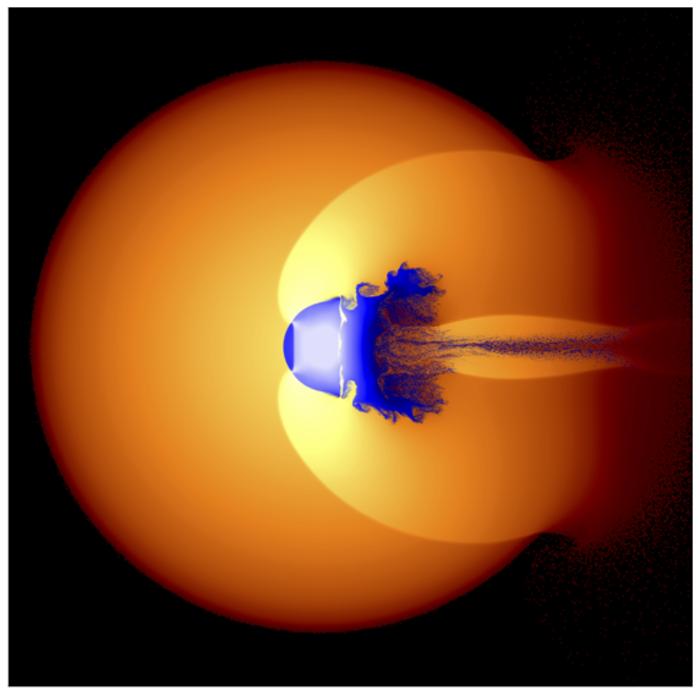

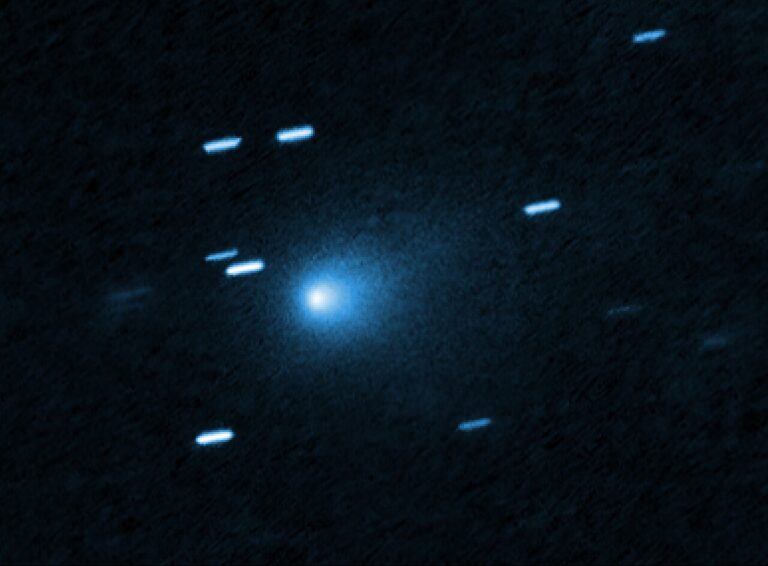

“At this point, we believe that a large fraction of the illuminated comet’s surface is displaying some level of activity,” said Jean-Baptiste Vincent from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany. During the past few weeks, the OSIRIS team has witnessed a gradual but qualitative change. “In the first images from this summer that showed distinct jets of dust leaving the comet, these jets were limited to the neck region,” said Holger Sierks from MPS. Now, jets appear also on the “body” and “head” of the comet.

Currently, still more than 279 million miles (450 million kilometers) are separating 67P from the Sun. Based on a rich history of ground-based observations, scientists expect a comet’s activity to pick up noticeably once it comes within 186 million miles (300 million kilometers) of the Sun. “Being able to monitor these emissions from up close for the first time gives us much more detailed insights,” said Sierks. From the OSIRIS images, the team now wants to derive a better understanding of the evolution of cometary activity and the physical processes driving it.

Since under normal circumstances the comet’s nucleus would outshine the jets, the necessary images must be drastically overexposed. “In addition, one image alone cannot tell us the whole story,” said Sierks. “From one image, we cannot discern exactly where on the surface a jet arises.” Instead, the researchers compare images of the same region taken from different angles in order to reconstruct the 3-D structure of the jets.

While 67P’s overall activity is clearly increasing, the mission’s designated Philae landing site on the “head” of the comet still seems to be rather quiet. However, there is some indication that new active areas are waking up about 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) from landing area J, which Philae will set down on November 12. These would allow the lander’s instruments to study the comet’s activity from an even closer distance.